Illustration: Chen Xia/GT

When necessary, America does not shy away from using coercion and bullying to achieve its foreign policy goals, and the exertion of pressure is not always limited to its foes.The US has a long and undignified history of strongarming supposed allies into towing the line. When Washington's ambitions conflict with the better judgement of friendly nations, and those nations decline to comply with US demands, many an American president has - like a Mafia godfather - made them an offer they can't refuse.

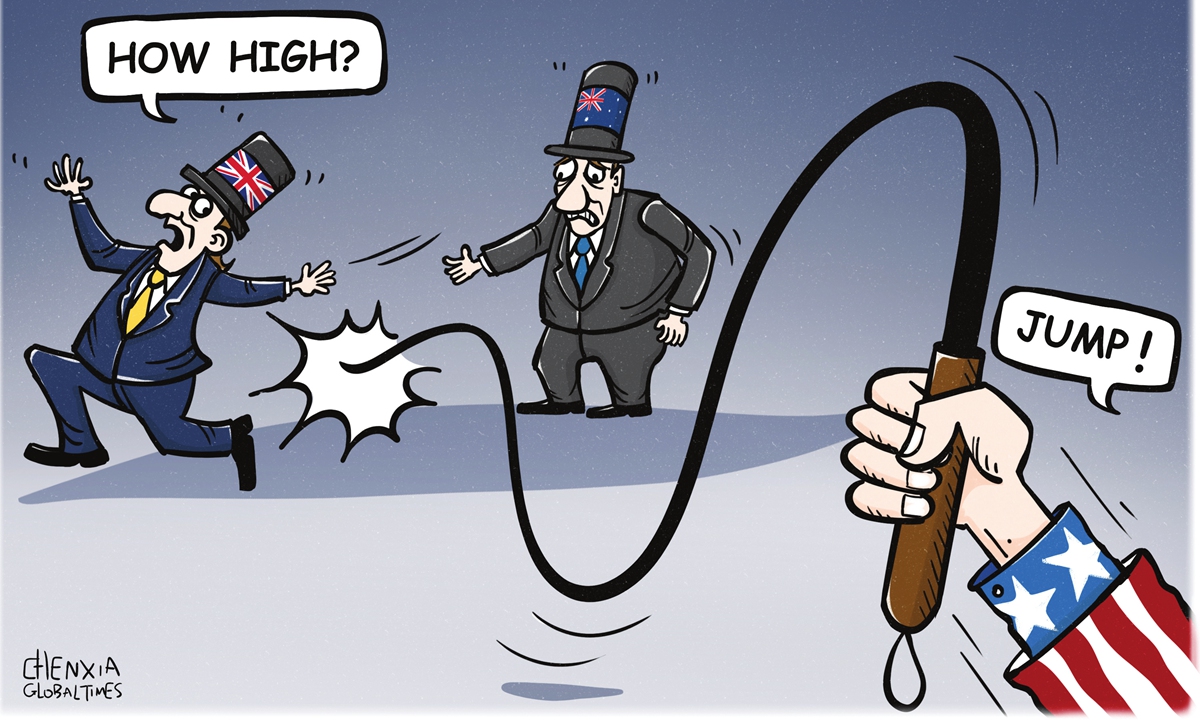

It means those countries which sidle up to the US for good reasons of statecraft will one day have foisted upon them a stark choice: "You're either with us, or against us." This even applies to Britain, despite the so-called special relationship. In reality, it's only "special" when it is in America's interests, like when Tony Blair followed George W. Bush into the so-called War on Terror and later into Iraq despite there being little evidence to support action, minimal public backing, and disapproval from the United Nations.

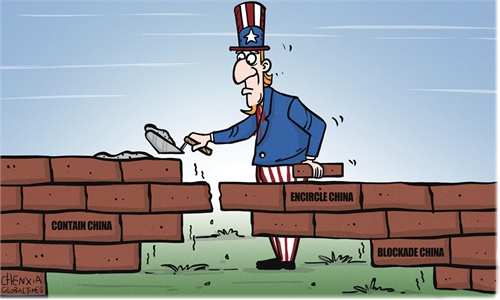

The occupants of the White House believe that if a country has benefitted from US friendship in the past, the US is entitled to expect undivided loyalty in the future. This is particularly evident when Uncle Sam's objective is to marshal international opinion against a state it regards as a strategic foe, or an economic or ideological rival. Especially if that rival is China.

Britain has felt this keenly since leaving the European Union. There was a hope that, desperate to secure new trading partners after losing its close economic links with the EU's remaining 27 members, it could find some form of deeper alliance with both the US and China. Then came Huawei, Hong Kong, Xinjiang and memorably the preposterous AUKUS security pact, amongst others.

As far back as 2015, then British prime minister David Cameron was talking up the prospects of closer trading ties with China and heralding the dawn of a "golden age" in the relationship between London and Beijing. The UK became the first country outside Asia and the first G7 member to ratify the Articles of Agreement of the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank and earlier this year the current chancellor Rishi Sunak was working toward a trade deal with China. The sale of the British microchip company Newport Wafer Fab to a Dutch firm with a Chinese owner was approved. Approval was also given for Chinese investment in the construction of the £20bn Sizewell C nuclear power plant in Sussex.

Then, the "golden age" suddenly seemed to lose its luster.

America - dismayed that the UK and other European countries were still dealing with Huawei - turned the screw by imposing sanctions which prevented any American technology being used in systems alongside Huawei's. This triggered exactly the response the Americans desired - it compelled Britain to cancel the deal (the first in Europe to do so) and announce all Huawei tech will be removed from its systems by 2027. Departing Prime Minister Boris Johnson admitted that he had caved in to pressure from the US. Shortly afterward, it was revealed the government was unhappy with China's 20-percent share in the Sizewell project - and two months ago Her Majesty's Government bought an option to take on the Chinese manufacturer CGN's role. The sale of the Newport chip manufacturer has now also been put on hold pending a government review. It is hard to credit that the ground has shifted so significantly, so quickly: a warm and friendly China-UK relationship has turned frigid under Washington's influence. It is no coincidence that Britain's China policies now dovetail with those of the US.

This is not only a British phenomenon.

Australia has slavishly followed US interests with catastrophic consequences, being dragged into conflicts like Vietnam and Afghanistan. Now, despite Australia's largest trading partner being China, Canberra has allowed itself to be pressed into the new AUKUS pact with the UK and the US, committing it to building a fleet of nuclear-powered submarines it does not need and which many of its citizens do not want. Britain's involvement also commits it to a more visible presence in the Indo-Pacific region, which the US has repeatedly sought. Against their better judgement the UK and Australia are part of a coalition to counter what the US sees as increased Chinese influence in the region: they are committed to this ridiculous response.

American power is often projected through its relationships with its allies, but it serves only American interests. Too often, a country hears the crack of America's whip and its exhortation to "Jump!" and too often responds by asking "How high?"

The author is a journalist and lecturer living in Britain. opinion@globaltimes.com.cn