Faster and fresher, a deliveryman's career shows transformation of China's modern life in a decade

Qi Nannan delivers a parcel in Shitou Hutong. Photo: Li Hao/GT

Editor's Note:

Over the last decade, China has witnessed tremendous changes, which could not have been achieved without the hard work of its people.

There are many ways to record the last decade, but the story that, at times, leaves a mark on each person is surely the most vivid. To greet the 20th National Congress of the Communist Party of China (CPC) scheduled to be held later this year, the Global Times has launched a series of stories to acknowledge the remarkable contributions made by people from all walks of life who have dedicated their wisdom and energy to the realization of the Chinese Dream.

In this installment, a deliveryman who works in a Beijing hutong shares his experience of serving elderly residents in the neighborhood, offering a "down-to-earth" perspective to understanding how the logistics industry prospered and brought convenience to the public.

When Qi Nannan started working as a deliveryman in 2016 by chance, he did not expect to remain in the post for very long. But six years on, he still works at a delivery services and logistics company branch in central Beijing's traditional hutong area, with a deeper insight into the industry and a strong sense of professional pride.

Before joining the company, Qi, from outside of Beijing, had been on the lookout for a company that would contribute to his social insurance so that his daughter could be enrolled into a local primary school. Before that, Qi had run his own small business.

He recalled the moment when the proposal of a deliveryman was made to him - flexible working hours, a reasonable salary, and relatively few educational qualification requirements, yet tiring and "not" a decent job societally.

Shitou Hutong where his job covers is an old urban area with some of the buildings in the area having been built long before the founding of modern China.

Now, some of the classic quadrangle courtyards are owned by single families but many more are shared among several households without doorplates to differentiate them.

Qi's first lesson was to make sense of the addresses in a "maze-like area."

The second was to overcome the frustration of being "overlooked and disrespected."

The job requires one to employ a rushed approach to work on a daily basis, spending long hours outside in the baking summer heat or brutal winter cold, and a humble acceptance that people might not notice your efforts.

On occasion, Qi need to deal with "really difficult" customers who complain about late deliveries or dispatches.

He initially considered quitting multiple times, but the station was short-staffed so he agreed to stay until a replacement could be found.

He however remained while numerous new hires came and went.

Being important and proud

Qi cannot remember a turning point when he was determined to stay in the industry, because his professional pride has grown over time, along with a composite of touching moments, and Chinese President Xi Jinping's unexpected inspection of his facility ahead of Spring Festival on February 1, 2019 being a climax.

Xi visited the delivery facility and asked about delivery workers' lives, praising them for their hard work and sending his cordial greetings to the country's 3 million delivery workers at that time.

"It was such a surprise, and President Xi was very kind," Qi recalled, saying that was a moment in which he felt important and proud.

The visit was aired in a TV news program by national broadcaster and was a source of pride for Qi's daughter, who told her classmates "My dad was on TV! President Xi shook hands with him."

Before joining the company, Qi, from outside of Beijing, had been on the lookout for a company that would contribute to his social insurance so that his daughter could be enrolled into a local primary school. Before that, Qi had run his own small business.

He recalled the moment when the proposal of a deliveryman was made to him - flexible working hours, a reasonable salary, and relatively few educational qualification requirements, yet tiring and "not" a decent job societally.

Shitou Hutong where his job covers is an old urban area with some of the buildings in the area having been built long before the founding of modern China.

Now, some of the classic quadrangle courtyards are owned by single families but many more are shared among several households without doorplates to differentiate them.

Qi's first lesson was to make sense of the addresses in a "maze-like area."

The second was to overcome the frustration of being "overlooked and disrespected."

The job requires one to employ a rushed approach to work on a daily basis, spending long hours outside in the baking summer heat or brutal winter cold, and a humble acceptance that people might not notice your efforts.

On occasion, Qi need to deal with "really difficult" customers who complain about late deliveries or dispatches.

He initially considered quitting multiple times, but the station was short-staffed so he agreed to stay until a replacement could be found.

He however remained while numerous new hires came and went.

Being important and proud

Qi cannot remember a turning point when he was determined to stay in the industry, because his professional pride has grown over time, along with a composite of touching moments, and Chinese President Xi Jinping's unexpected inspection of his facility ahead of Spring Festival on February 1, 2019 being a climax.

Xi visited the delivery facility and asked about delivery workers' lives, praising them for their hard work and sending his cordial greetings to the country's 3 million delivery workers at that time.

"It was such a surprise, and President Xi was very kind," Qi recalled, saying that was a moment in which he felt important and proud.

The visit was aired in a TV news program by national broadcaster and was a source of pride for Qi's daughter, who told her classmates "My dad was on TV! President Xi shook hands with him."

Qi Nannan works in the narrow hutong area in central Beijing. Photo: Li Hao/GT

On that day, like so many others, Qi was busy packing and loading up packages while his colleagues busied themselves with delivering the parcels as soon as possible which mostly consisted of gifts and necessities people bought around Spring Festival.

Their hard work received smiles and warm greetings from residents in return. During peak seasons when packages keep flooding in, particularly around shopping festivals, residents drop by and leave some snacks and drinks for the couriers who are too busy to take a break and have a real meal.

Sometimes after delivering a package to a household, they are rewarded with a popsicle or cold drink in summer.

Such acts of kindness foster the idea that "we are not staff and customers, but close friends," Qi said.

Putting their trust in couriers, residents also share their stories and feelings while mailing and signing for packages. A middle-aged auntie once requested that Qi to pack up her parcel securely to ensure the homemade pork knuckles would quickly and safely reach her son who works in another city.

Qi, while in casual exchanges, is offered a glimpse into clients' lives.

One elderly man would go to Qi every month to mail pickled vegetables from "liubiju," a time-honored Beijing brand, to his elder sister in Shanghai.

The man once said, "We are all elderly; neither of us can visit the other. But she loves these pickles so I mail them to her every month. Thank you [couriers], thank you for sending my affection."

Qi noted "I realize, through such moments, that I was not only sending an object. I am a messenger of love and family affection."

Memories of the epidemic

When the COVID-19 suddenly struck, Qi and his colleagues felt strong solidarity from the community. Such love and mutual support were expressed with boxes of masks, disinfectants, and all sorts of other useful supplies which people opted to purchase online.

In the early days of the epidemic, Qi and his colleagues helped community residents to overcome challenges in securing supplies as they were among the few still allowed relative mobility when the country was brought to a halt by the virus. Wang Yong, who was a courier in Wuhan, Central China's Hubei Province when the virus suddenly raged the city, became one of the most well-known deliverymen in the country.

Wang volunteered his time to ferry medical workers to and from their homes to designated hospitals and back during the Wuhan lockdown when public transportation had been halted, so that medics can have a good rest and rescue more lives.

He left home without knowing when he would return on January 25, 2020, starting a heroic chapter in his life story.

Wang later made appeals online for more to join in and formed a real-life superhero squad, coordinating resources to provide boxed meals for medical staff and allocating medical supplies.

To Qi, Wang is a source of inspiration, and a compelling example of what a "hero" a deliveryman can become in challenging times.

Qi and his colleagues also volunteered to organize mass screening of residents, and he remembered reading news reports on how a deliveryman immediately became a community volunteer after being accidentally sealed in a virus-hit residential compound.

Delivery workers were the backbone and lifeline which ensured the functioning of Chinese society amid epidemic prevention control restrictions, many people said.

The sense of inferiority Qi had at the very beginning of his career has completely vanished, with Qi now feeling a sense of purpose in helping others through hard times like the epidemic, in making others' lives easier, and in providing others with convenience through fast, efficient deliveries fueled by a booming e-commerce industry.

Observations through the decade

Over those years, Qi noticed a change of the types of goods people send and receive, around festivals as well as in daily life, which reflects a gradual change in lifestyle among ordinary Chinese people.

A decade ago, express delivery was mostly used for valuable objects and important documents. Qi had heard of couriers in charge of Beijing's Zhonguancun area, China's "silicon valley," who had made quite a fortune through commission fees from the business. "Some were able to buy multiple houses and could afford luxurious sports cars through hard work."

Today, Qi is hardly surprised by what he sees being mailed - from tropical fruits and ice cream to flowers and seafood. The variety of festival presents has been largely enriched by express delivery via flight and road transportation.

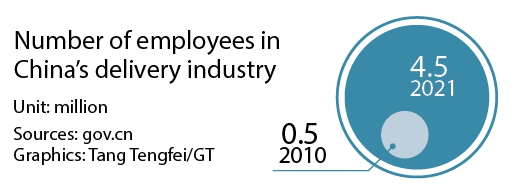

To understand the changes in numbers, the value of the cargo transported in China's logistics sector in 2012 was 177 trillion yuan ($26 trillion) in 2012, of which 162 trillion yuan, or 91.5 percent, were manufactured products.

As for 2021, still under the impact of the COVID-19 epidemic, the sector was valued at 335 trillion yuan, and consumer goods alone made up more than 10 trillion yuan, with agricultural products and imports being large contributors. Another notable facet was renewable resources logistics, which earned 2.5 trillion yuan, a 40 percent increase year on year.

E-commerce has also experienced explosive development in the last decade. Online shopping was in a rapid developing phase but still uncommon for residents in Shitou Hutong, most of whom were elderly when Qi started to work as a deliveryman. But an increasing number have since caught up with the trend and the epidemic has also acted as catalyst.

In lower-tier cities, and even counties and townships, people can receive what they ordered online in days, which was unimaginable a decade ago. Such a scenario would be impossible without the construction and upgrade of highways and village roads, as well as the robust development of aviation.

Deliverymen learn about traffic rules in Suzhou, East China's Jiangsu Province on July 31, 2020. Photo: VCG

According to a central government plan issued in 2021, China is eying a "global123" logistics system by 2035 - delivery in one day for domestic goods, in two days for neighboring countries, and in three days for major cities globally.

In the period between 2021-25, 100 key national cold-chain bases and 70 major logistics hubs have been planned.

Qi also noted the digitization and provision of smart services in his daily work, which is consistent with the major trends in the industry.

When Qi started working as a deliveryman, handwritten forms were more common and he had to memorize the identification numbers for different places to speed up the mailing process. "If the handwriting was not clear, or two different places had the same name, the package was likely to be mailed to a wrong place."

Today, most of the delivery orders are online - a customer places an order through WeChat or other mobile phone apps, the corresponding order fee is calculated automatically and charged through e-payment, and the package can be tracked all the way until its arrival at the right place.

At distribution centers, industrial robots are increasingly being used to spare workers from heavy lifting and also reduce instances of human errors.

"Don't you feel the instances of the 'package missing on the way' rarely occur now?"

Delivery workers are like the blood vessels of a society: Qi and his colleague in communities are capillaries while those working in distribution centers and transportation links are the main vessels. And changes in their lives offer some insight into China's progress in the last decade.

Qi has no plan to leave his cherished post and will continue to observe China's development from the grassroots perspective.