Illustration: Xia Qing/GT

It is difficult for a Western journalist to report about China in an unbiased manner. The reasons for this are four fold: professional, ideological, geopolitical and - tying them all together - financial.

International events coverage has changed massively in the UK in barely a generation. Decades ago, I worked for a national newspaper which once boasted a correspondent in every capital city on Earth, and I was eventually left occupying the outpost most distant from its London HQ - a small provincial English town about 250 miles to the north. As all media similarly shrank their staff, they relied on fewer sources of information and so fostered a narrower worldview among their listeners, viewers and readers.

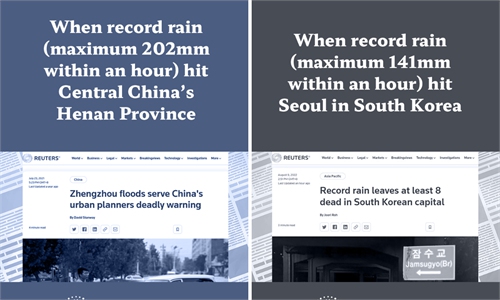

The nature of Western reporting also has an impact. Newsgathering's predominant focus is not on the ordinary, but the extraordinary: a disaster or failure becomes news more readily than everyday life. This media lens, and fewer staff to seek alternatives, normalizes the hearing of bad news from China.

Reporters making innumerable subjective judgements in the process of assembling a story they are supposed to tell objectively, are always at risk from unconscious bias. But they can also be expected to parrot their employers' editorial line, and an unbalanced story can masquerade as an authentic piece of journalism. It can be more subtle than crudely distorting facts.

What is written can be less important than how it is written. What is included can be less important than what is left out. The choice of language and emphasis is key. Coverage of China events can seem like a barrage of hypercritical rhetoric, not always contiguous with the facts. It can shape public opinion with loaded language like "threat," "challenge," or "aggression." Demonstrations become "riots," deradicalization programs become "repression," schools become "camps."

Many media organizations, particularly in the UK and the US, also have a built-in news agenda which determines stories from China, good or bad, being told in a partisan way which reflects poorly on Beijing. The reasons for this are complex, but media ownership is critical to the way decisions are made. Billionaires and conglomerates control the media in the UK and the US, a concentration of ownership which enables a wealthy elite to control the flow of information to people in an economic system in which the media are an integral part and which they need to protect.

In 2021, 90 percent of Britain's national newspapers were owned by three companies (including, obviously Rupert Murdoch's). This year, 90 percent of the American media is controlled by just six giant corporations whose executives similarly call the news shots. Right-wing think tanks such as the US government-funded National Endowment for Democracy produce "research" which feeds into the media machine, often repeated without challenge. In this way, governments get column inches with a veneer of veracity as easily as buying advertising space.

By faithfully promoting a status quo which essentially serves the preservation of American hegemony (and where the US leads in foreign affairs, the UK almost invariably follows), the media are a powerful weapon in the projection of Western foreign policy. They were used to encourage support for war in Afghanistan and Iraq, for deep military involvement in Ukraine and are now being mobilized to generate anti-China sentiment over Taiwan.

Ideologically, Western capitalism's most overriding concern is for self-preservation and it sees China's alternative system of governance as a challenge. It believes that anything undermining the American global supremacy that Washington has always taken for granted must be confronted. China's extraordinary economic miracle which has lifted 800 million people out of poverty in a system of socialism with Chinese characteristics is seen as a threat to neoliberal values.

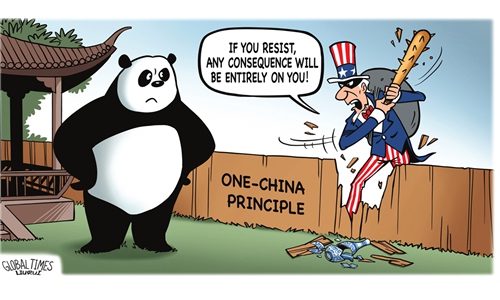

The West addresses this perceived threat with what it understands best: force. This can be economic sanctions or tariffs, or military might, such as the ring of US military outposts which circle China like a noose, or a naval presence around Chinese territorial waters. Most recently, there was the confected outrage over Taiwan triggered by Nancy Pelosi's provocative visit. It was no coincidence that President Biden's Chips and Science Act followed quickly. He walked through a door which Pelosi opened, and which the media held ajar. Now, relations between China and the US are worse than for decades.

News coverage of China in the UK is dominated by a handful of subjects, and all of them are framed in a manner representing China's action in these areas as a threat to Western interests in specific areas: the economy, foreign policy, military and security, China's unique political system is presented as a threat to US dominant, pre-eminent position on the world stage (and therefore to its allies, like Britain).

The consequences of this type of unremitting negative coverage can be measured by only one metric, that of rising tensions between nations. As most recently demonstrated in the role it played in ramping up tension over Taiwan, this kind of media behaviour leads only in one direction: down, towards the risk of conflict. The way the media reports on China, at the behest of governments - wittingly or unwittingly - can only risk destabilizing a region where stability should be the only way forward. It's a dangerous game to play.

The author is a journalist and lecturer living in Britain. opinion@globaltimes.com.cn