An ancient painting depicts the Han Dynasty's Zhang Qian, China's Silk Road explorer, on a mission to the West. Photo: Courtesy of Wang Hui

Bronze cookware discovered in the Han Dynasty Tomb of Marquis of Haihun. Photo: Courtesy of Wang Hui

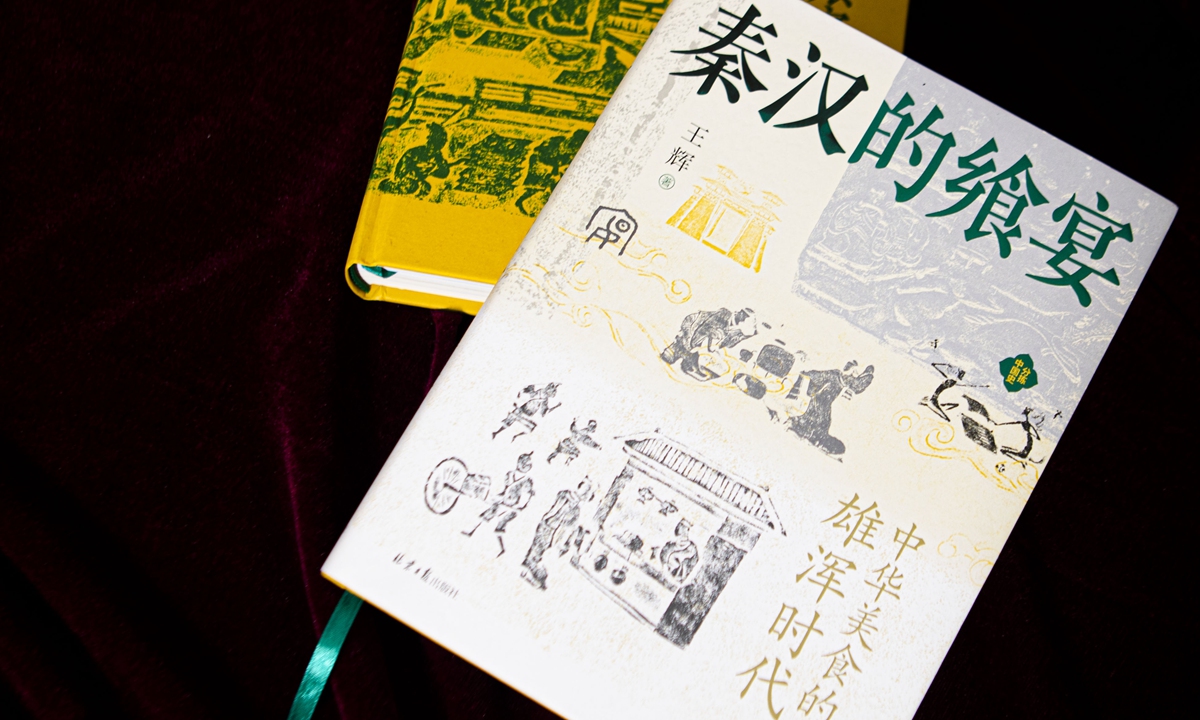

Feasts in the Qin and Han Dynasties Photo: Courtesy of Wang Hui

Be it the 13th century when Italian explorer Marco Polo brought Chinese "ice cream" to Europe or the Eastern Han Dynasty (25-220) when messenger Zhang Qian brought the techniques of making red wine into China, food culture has always been a window to examine the constant cultural exchanges between China and the West.

This topic still inspires both Chinese and Western culturalists today. The book Feasts in the Qin and Han Dynasties is one of the latest contributions to the conversation by exploring the shared cultural links between China and the West through the culinary arts of the Qin (221BC-206BC) and Han (206BC-AD220)dynasties - a time when China's culinary tradition began to take shape.

Exchanging recipes The Qin and Han dynasties were the first prosperous period in Chinese history. Feasts in the Qin and Han Dynasties's author Wang Hui told the Global Times that the culinary culture of this period absorbed a diverse range of foods from numerous sources, making it a symbol of China-West cultural communication.

In ancient times, Zhang Qian, China's Silk Road explorer, brought food such as grapes and the art of making red wine to China. Such imported foods were quickly woven into China's own cultural system, leading to various localized expressions.

The Chinese word "hu," meaning "foreign," often appears in the names for food introduced from foreign cultures such as pepper, or hujiao, and cucumbers, traditionally called hugua.

"The localization of food shows China's culinary wisdom. This is not only reflected in these types of names, but also about how they are prepared. The same cucumber, how we cook and cut it all shows Chinese characteristics, which allowed these imported foods to stay on our tables," Xiang Qing, a food culture researcher in Guangzhou, Guangdong Province, told the Global Times.

The tradition of individual servings was one of the topics that interested Wang, especially after "food sanitation" became a globally discussed topic during the pandemic.

Wang told the Global Times that individual servings, common in Western culture, had already appeared in China around the Sui (581-618) and Tang (618-907) dynasties.

Yet unlike the Western "per serving" tradition that focuses on individual eaters, China packs "food sanitation" and its "common shared dish" tradition into one.

"In the painting Night Revels of Han Xizai, we see the same dishes being served to eaters on individual plates. This preserves food sanitation as well as shows the Chinese belief in harmony and collectivism," Wang noted.

Wang said that ancient Chinese had also begun to adopt a "scientific diet structure" and set out on the pursuit of savory flavors and cooking methods that later hugely inspired Western food culture authors such as Fuchsia Dunlop, a keen British lover of Chinese food who spent 20 years on exploring Chinese recipes.

Known for her work Shark's Fin and Sichuan Pepper, Dunlop explores Sichuan cuisine's unique flavors, which to Wang are a "special seasoning" that reflects the Chinese belief of "different but still in harmony."

"Westerners love Chinese food because we combine scent, appearance, taste and color together. This is different than what they do in their culture, but when such 'thoughtful' and 'harmonious' characteristics can be tasted directly, Westerners can understand us better," Wang explained.

"Chinese food is very popular so I suppose it's the best way for people to get to know China and to have a positive image of China," Dunlop told the Global Times.

Food for thought Covering 2,000 years of Chinese culinary history over the five chapters of his book, Wang noted that ancient dietary customs still inform people's contemporary lives today both at and away from the table.

Loved by modern people as one of the top midnight snacks, skewered barbecue originated from the ancient Chinese cooking method called zhi, which means skewering meat on a stick to cook.

"Ancient Chinese were even more creative than us today. They used not only standard ingredients such as beef and chicken, but also cicada and quail. This shows a very Asian idea of how humans exist with nature," Wang noted.

Even common greetings such as "Have you eaten your meal" was also inherited from ancient people's tradition of eating various grains.

"That we use such food terms in everyday life, or the order in which we sit at the table shows Chinese qualities such as unity and fraternity, courtesy and humility," Xiang noted.

"[French politician] Jean Anthelme Brillat-Savarin once said, 'Tell me what you eat, and I will tell you what you are.' The China's rich and ancient food culture not only includes food itself, but also contains profound philosophy, art and even the principle of governing the country in peace," Wang remarked.