US fickleness brings Europeans anger as countries face energy crisis, disruption

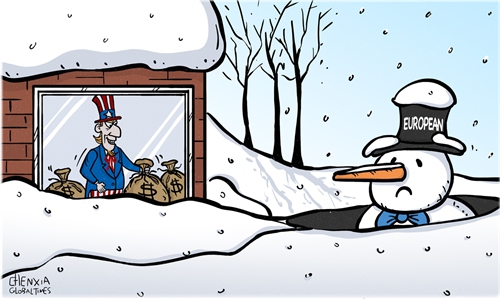

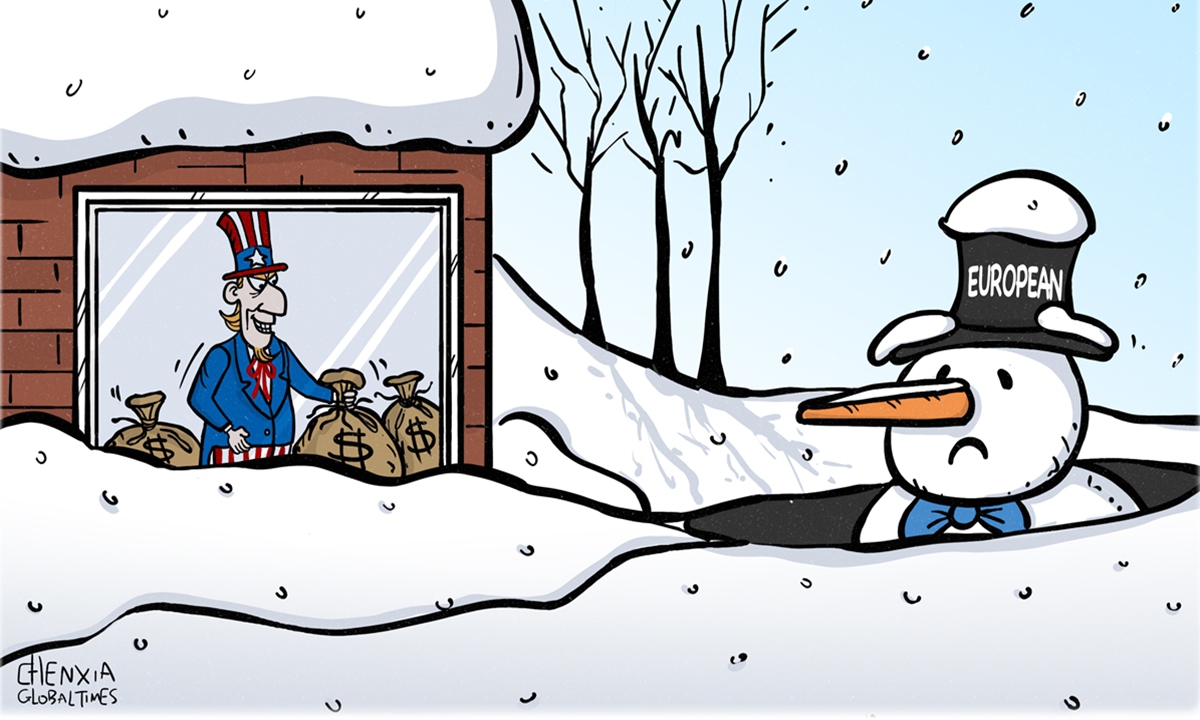

Illustration: Chen Xia/GT

There's a famous phrase in a Shakespeare play referring to a "winter of discontent," an expression which has often been borrowed by Britain's media to describe industrial unrest during that coldest of seasons. However, this winter the phrase could well be used to describe an outpouring of anger by the entire population, who are unaccustomed to having their comparatively high standard of living threatened.Ordinary people have already been taking to the streets to protest at unprecedented energy prices and the seeming inability, or unwillingness, of government to find a solution. Unless an answer is found, this winter could be one of discontent the like of which has never been seen before.

The threat is so concerning that academics, forecasters and other experts are warning that public fury will not only spill over into marches on the streets of cities around the world, but also that the rage felt by citizens will drive the kind of civil disruption that can bring down governments.

In Britain, there have been warnings that 65.8 percent of all UK households will be in fuel poverty by January. Many are already forced to choose between buying food and paying for energy - sometimes a choice between feeding their children and keeping them warm. And this winter, household heating bills are likely to hit record highs.

There is already plenty of evidence of this simmering discontent. Activists in Britain have called for a boycott of energy bills from next month and trade unions have staged a series of mass rallies demanding higher wages, lower fuel and food costs, alongside higher taxes on wealthy individuals and profiteering energy producers. There have also been strikes in the UK, France, Spain and Belgium for higher pay among public workers whose salaries cannot match surging inflation.

Soaring global energy prices are pushing up the cost of almost every imaginable commodity - especially heating and food, and the means to cook it. Desperate people driven to the edge by years of austerity measures and precarious employment may reach a tipping point.

Western governments have been quick to blame the war in Ukraine for pushing up fuel and gas prices, and it is true the conflict has had a devastating impact on international energy markets. However, the story is more complicated than that, and it dates back to before Kiev's conflict with Moscow even began. And it sits awkwardly with claims by the US and its allies that Russia is fully to blame.

As early as 2020, deep supply cuts were agreed by the Organisation of Petroleum Exporting Countries or OPEC (which includes the world's second-largest producer Saudi Arabia) and Russia at the urging of the US, whose then president Donald Trump wanted to protect the US oil industry, which has grown to become one of the world's largest oil producers thanks in part to a domestic boom in fracking.

However, the Biden administration backtracked on this and urged increased production of oil - blaming what it calls the OPEC "cartel" for failing to turn supplies of crude back up quickly enough. Both under Trump and Biden, the US sought to first raise, and then lower what are now runaway global prices, to suit its own domestic agenda. It is significant that the White House asked for production to be speeded up only after the invasion of Ukraine made worse an already bad situation in worldwide fuel costs. Acknowledging the elephant in the room, the Saudis have blamed the US' fickleness for causing its own fuel crisis - and the crises of other countries around the world.

Some would argue that the sheer scale of Western military backing for Ukraine against Russia is only prolonging the war, rather than ending it, and therefore exacerbating the energy crisis. There is also the perverse contradiction that the US-led sanctions regime against the Russian oil industry has caused prices to soar. This has led, counterintuitively, to producers - including Russia - making phenomenal profits. At the same time, the governments of Europe and the UK, and the US, seem to struggle to pay for adequate measures which their populations need to survive the winter, as their energy bills - and the profits of producers - spike. And if there is a chance that the people might struggle to survive the winter, there is an even greater chance that their governments will not.

The author is a journalist and lecturer living in Britain. opinion@globaltimes.com.cn