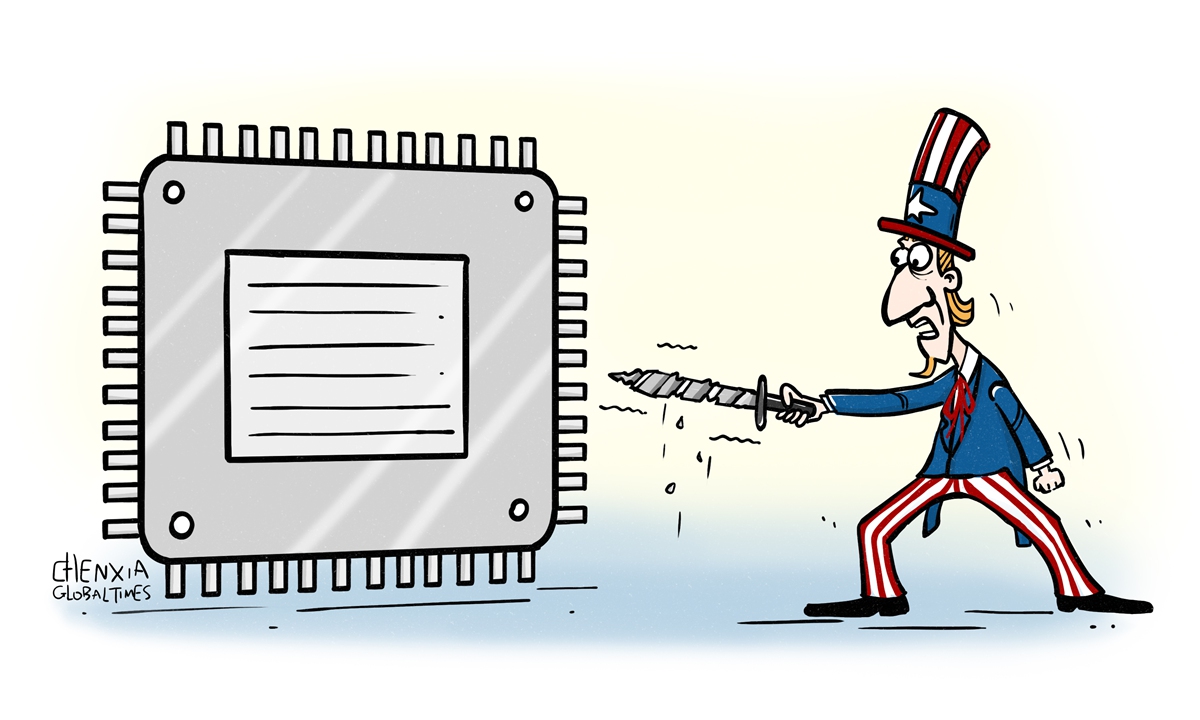

Illustration: Chen Xia/Global Times

We are all in the same boat; we rise and fall together. This was what the US championed when it stood unrivalled, stewarding the world with self-confidence and a sense of mission. But no longer. It has started to feel insecure, not least about cutting-edge technologies like semiconductors, and even fear that its seat as the helmsman might soon be taken.

The share of US-based modern semiconductor manufacturing capacity has eroded away from 37 percent in 1990 to 12 percent in the early 2020s. The country currently has no capacity to fabricate the most advanced microchips at home. Plus, its production of high-end chips lags behind both China's Taiwan region and South Korea, with R&D and capital investment falling short too.

To sustain its sway, the country that chafes at following the lead of others is wielding tools previously despised by itself. In early August, President Joe Biden signed into law the CHIPS and Science Act that provides financial incentives for boosting the domestic supply of semiconductors, including subsidies and tax cuts, something hardly compatible with any "liberal" economic system.

The US is unequivocal about federal support for its semiconductor sector. The Act earmarks $52.7 billion for "American semiconductor research, development, manufacturing, and workforce development," and provides a 25 percent investment tax credit for the production of semiconductors and related equipment. This huge expenditure serves a clear objective set out by the government -- to revitalize domestic manufacturing and enhance supply chain resilience. Such statist planning, together with the industrial policy designed for one sector, is rarely seen in the US. After all, this country detests intervention so much that it coined the expression "state capitalism" for economies where "the state is the principal actor and judge, and uses markets for political gain."

The government appropriation does not come for free, but with "strong guardrails" prohibiting recipient companies from building certain facilities in China and other "countries of concern" for 10 years. Amidst what the US calls "stiff competition" with China, the Department of Commerce, responsible for fleshing out and implementing the Act, may be empowered to censor American semiconductor businesses to ensure compliance, and dictate the exemptions for doing business with the flagged countries.

Once a seeming fundamentalist of globalization peddling the liberal economic order, the US is now reneging on its commitment to the WTO, which prohibits "subsidies contingent, whether solely or as one of several other conditions, upon the use of domestic over imported goods," and "specific subsidy" that "explicitly limits access to a subsidy to certain enterprises."

As Washington now sees it, it's time that the world moved on from globalization to Americanization. It spares no efforts to build neo-colonies for US strategic supplies and technologies. On the supply side, the US campaigns to reduce reliance on others and bring production back home. Morris Chang, co-founder of Taiwan's chip producer TSMC, criticized that Intel and other US companies argue for onshoring the chip supply chains out of "selfish interests." The US Commerce Department even asked major chip companies, including TSMC and Samsung, to "voluntarily" submit key information, sometimes trade secrets. If companies refuse to cooperate, the US has other tools available to require them to provide the data needed, said Gina Raimondo, the Commerce Secretary.

On the demand side, the US has long added Huawei and other Chinese hi-tech companies to a list of firms with which American companies cannot do business, unless officially permitted. The latest "poison pill" in the CHIPS Act will further strain business ties between China and the US along the semiconductor industrial chains.

The US also forces its allies to select business partners along ideological lines. A former British intelligence officer revealed in a recent article that the Deputy National Security Advisor under former President Donald Trump once yelled for five hours at British officials, demanding them to remove Huawei from British telecommunication networks without giving any convincing rationale.

But cutting China out hardly does any good to US interests or its image. China's semiconductor import bill totals $300 billion a year. In 2018, a quarter of that bill came from US companies. And US companies could lose 18 percentage points of global share and 37 percent of their revenues if the government completely bans sales to Chinese customers, according to the US-based Boston Consulting Group.

While trying hard to decouple in the semiconductor sector, what the US is doing now amounts to taking out the chip out of a computer, leaving everyone in the system to bear the consequence.

The author is a commentator on international affairs, writing regularly for CGTN, Global Times, Xinhua News Agency, etc. He can be reached at xinping604@gmail.com