As US-triggered Ukraine crisis prolongs, EU faces grim prospect of deindustrialization

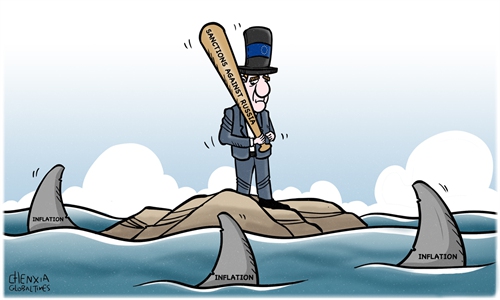

Illustration: Chen Xia/GT

"Deindustrialization," which has been hotly discussed in Europe recently, overshadows the efforts of Western developed countries to rebuild their industrialization."Deindustrialization" is not new in Western countries. Since the 1970s, industries in Europe and the US have been moving out of their countries for comprehensive reasons. But the newest wave of "Deindustrialization" Europe is facing this time is largely influenced by a single effect, that is, rising energy prices and imported inflation, further exposing all old problems that already existed.

For several decades, the rising proportion of tertiary industries, including financial and service industries in the Western world was the overall trend. Second, those countries would deliberately shift their manufacturing industries abroad due to globalization and the rising costs of production. Many developed countries have increasingly put forward the goal of "reindustrialization" in the early 21st century.

Now, electricity and gas prices have soared because of the Russia-Ukraine conflict. In an open letter to EU leaders, including Ursula von der Leyen, the President of the European Commission, European industry association Eurometaux raised the alarm about Europe's escalating energy crisis posing an "existential threat" to industry, calling on EU and member state leaders to "take emergency action to preserve their strategic electricity-intensive industries and prevent permanent job losses."

Growing costs will cause a lack of industrial raw materials in Europe, including metals. Together with soaring energy prices, as well as the rise in import prices due to the devaluation of the euro, the decline of profit margins will bring troubles to both the enterprises and the broader manufacturing industry.

As a result, the effects of the Russia-Ukraine conflict are another burden on Europe's unresolved problem of past deindustrialization.

Of course, decision-making errors also contribute to the current energy shortage in Europe, with some countries having put forward radical energy transition goals, including the decision to phase out nuclear power, the negative impact of which has just been catalysed by the crisis in Ukraine. Facing energy difficulties, some European countries were forced to boost coal use or extend the life of some nuclear reactors, which now leave them further away from Europe's earlier energy ambitions, Wang Shuo, a professor at the School of International Relations of Beijing Foreign Studies University, told the Global Times.

Moreover, the EU had proposed a ban on long-term contracts to import natural gas into the bloc to end its reliance on foreign producers before the Russia-Ukraine conflict broke out, leaving no access for temporary purchases now.

If the German economy, the engine of European economy, slows down while its export-oriented model is hit, the entire eurozone economy will be affected, likely resulting in a technical recession in Europe from next year, according to Wang.

What's worse, there's not much hope for Europe to come up with any solutions in the next few years for energy shortages. Governments in the EU may have to turn to subsidies in facing higher prices of electricity, gas and oil, which draws another problem of "where does the money comes from?" Meanwhile, the European Central Bank has announced measures to tighten monetary policy in response to growing inflation, a policy which contradicts the proposal of potential large-scale subsidies. As a result, there is limited policy space for Europe, which will suffer more if the energy crisis drags on as the Russia-Ukraine conflict continues to prolong and escalate.

However, Europe, despite being an important stakeholder during this crisis, does not have the ability to address the problem since it is unable to influence the resolution of the conflict in Ukraine.

Indeed, there will be growing coordination between the US and Europe in terms of monetary and economic policies due to the US concerns the conflict brings about broader global market turmoil and affects US interests, but current US policy seems to be deliberately pushing the world further toward a crisis, rather than easing it, given that the Federal Reserve has just raised interest rates by 75 basis points for the third consecutive time. In doing so, it is using its monetary policy to pass on its domestic economic crisis to other countries.

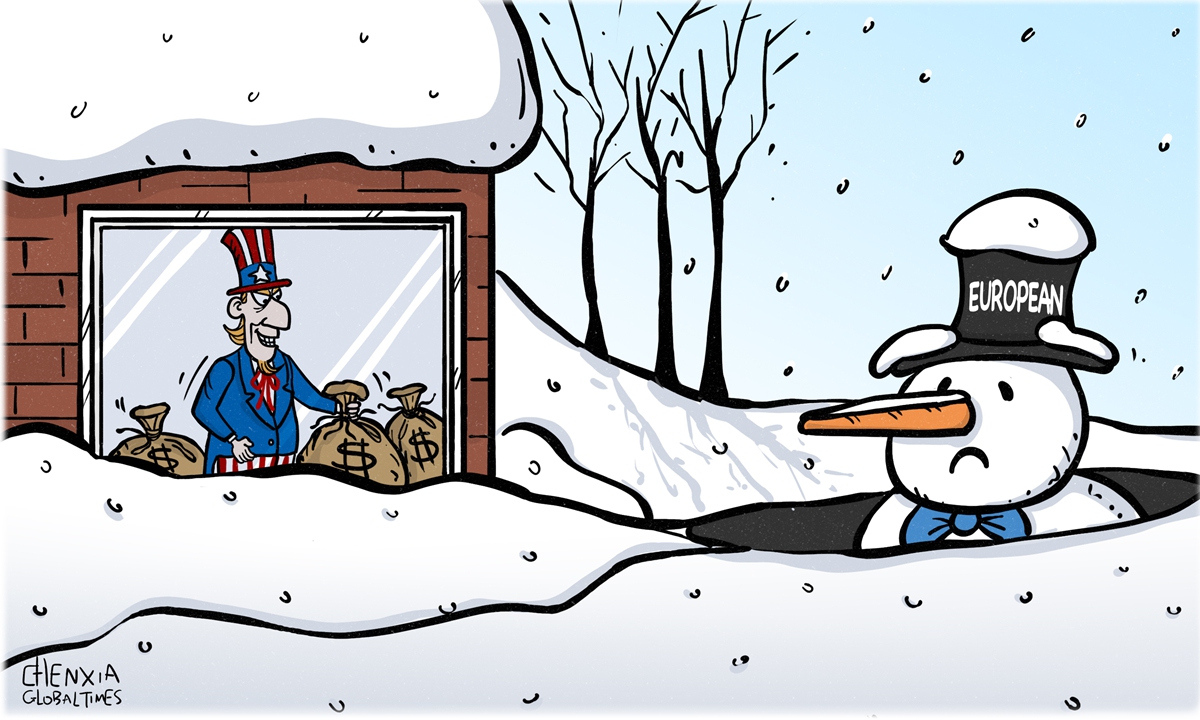

Furthermore, once the growing deindustrialization of Europe becomes a reality, the US may try to benefit from it by promoting the trend, because the US will become a preferential destination of European industries that choose to leave the continent.

This is the last thing Europeans want to see, which is to pay for the Russia-Ukraine conflict instigated by the US.

The author is a reporter with the Global Times. opinion@globaltimes.com.cn