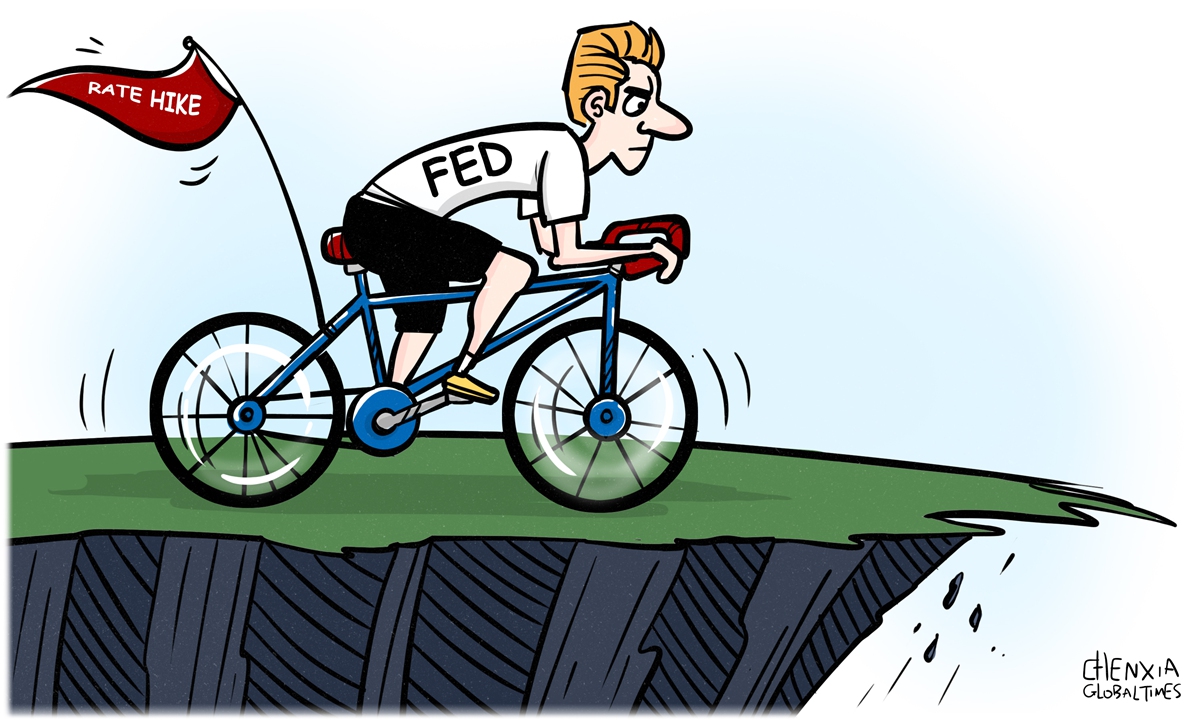

Illustration: Chen Xia/Global Times

Facing many months of persisting high inflation, the US Labor Department reported recently that the benchmark consumer price index, a major gauge of the country's inflation, slowed down to 7.7 percent year-on-year growth in October, from 8.2 percent in September and 9.1 percent in June, which was the highest in 40 years. The CPI measures what consumers pay for goods and services, and its decline should give the monetary policymakers a hard-won relief.Inspired by the news, financial markets across the world soared on the hope that previously staggering price rises and elevated inflationary pressure are now being curbed, finally, and the US economy might avoid a deep contraction in 2023.

Whether the US economy could come out of its traditional boom-and-bust cycle this time largely depends on the Federal Reserve's coming choice of monetary policy. The clear signs that workers' wage growth is slowing and the inflation is coming off the boil should build up the case for the US central bank to pause or slow raising interest rate soon.

In October, inflation-adjusted weekly earnings of American workers fell, and are down 3.7 percent in the last 12 months. Prices for used cars and trucks, which contributed heavily to inflation, dropped 2.4 percent in October from September. Food prices rose more slowly in October than in September, with grocery prices up 0.4 percent from the prior month, the smallest gain since December 2021. The price of gasoline, another major contributor to price rises, has remained volatile, and energy will remain a wild card when it comes to inflation in 2023.

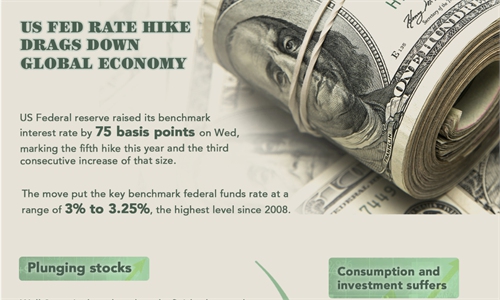

If the Fed chooses to continue its current strong monetary tightening measures by raising the federal-funds rate by 0.75 percentage point for the fifth time in a row during its next policy meeting on December 13-14, the US economic activity will be significantly watered down and cooled off, and consequentially, a deep recession will pop up quickly. The most appropriate move for the US central bank is to start adopting a piecemeal pace, raising the benchmark interest rate by 0.25 percentage point, or at most by half percentage point, in December.

Earlier this month, the US central bank raised its key interest rates to a fresh 14-year high after it approved the fourth consecutive rate increase of 0.75 percentage point, raising the federal-funds rate to a range between 3.75 percent and 4 percent, which is the highest since January 2008.

Now as the CPI is clearly moving downwards, market investors have gained a glimmer of encouragement that interest rates wouldn't have to rise to levels above 5 percent as previously estimated by the market. On Thursday in New York, the Dow Jones Industrial Average rallied more than 1,200 points, or 3.7 percent, and the benchmark S&P 500 index soared by 5.5 percent. China's stock market rose too on Friday, with the Shanghai composite index closing 51 points or 1.69 percent higher, while Hong Kong stock market's Hang Seng index surged by 7.7 percent.

The Fed officials have the luxury to see another month of inflation data from the Labor Department just before they convene their next policy meeting on December 13 and work out a policy decision the next day. There is a good chance that November's CPI rise could come up at between 7.2-7.4 percent as compared to October's 7.7 percent, which will further bolster the case that elevated inflation has been effectively tamped down, and the endpoint for the Fed's current cycle of rate rises is probably at a range between 4.75-5 percent.

However, some Fed officials including Chairman Jerome Powell have taken a more hawkish stance, saying that the US monetary policy will need to remain restrictive for some time to pull down inflation. Powell said that strong consumer demand, a tight labor market and more stubborn services price pressure in the US may continue to require the central bank to raise rates in 2023 to "slightly higher levels" than market investors had anticipated.

Higher interest rates mean higher borrowing cost, which make it less likely that people will spend on big-ticket items, such as homes, cars, computers, television sets or ramping up investment to expand their businesses, and that fall in demand will curb price rises.

But, inflation is unlikely to get to the Fed's target of 2 percent anytime soon, because the heady gains in American equity assets and the generous household savings enabled by the Biden Administration's $1.9 trillion pandemic rescue bill in early 2021 will continue to support relatively strong consumer spending. So, trying to keep US core price index at around 4 percent for an interval of 6-9 months might be more appropriate than the Fed's rush to hike the rates steeply to over 5.5 percent that will decimate the US economy.

As a matter of fact, the high inflation in the US has been fueled by the Fed's extraordinary monetary easing policy, or quantitative easing, and the US government's stimulus spending splurge in the aftermath of the outbreak of COVID-19 in 2020. The recklessness of the US central bank in slashing benchmark interest rate to around zero, while purchasing several trillions of government T-bonds and other securities, and keeping that easing policy for too long, has triggered the current round of runaway inflation. The conflict between Russia and Ukraine further stoked inflation in the world, driving up prices for energy, food and other commodities.

The author is an editor with the Global Times. bizopinion@globaltimes.com.cn