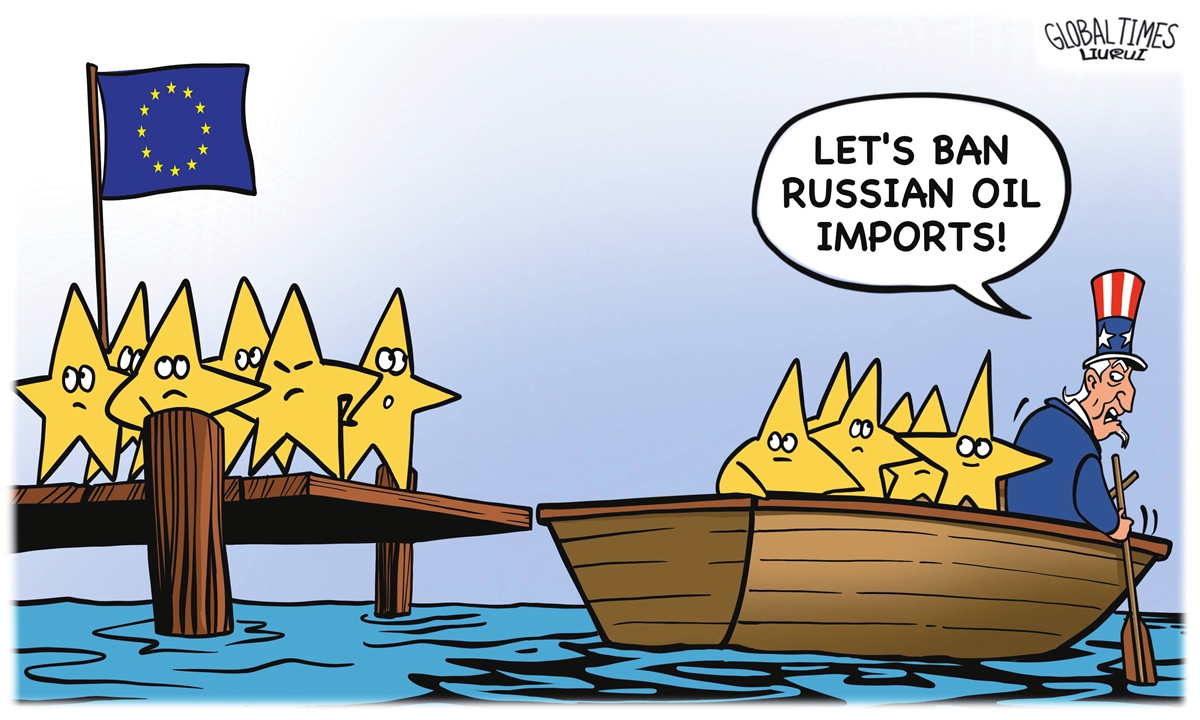

Cracks between US and Europe on sanctions Illustration: Liu Rui/GT

Following months of deliberation, the European Union finally agreed on a gas price cap as its latest attempt to reduce gas prices, a move that highlights the EU’s growing concerns over energy supply. But whether the move will help the bloc tame the energy crisis remains unknown, analysts said, warning that the EU's long-term energy crisis may drain manufacturing industries and harm its development.

In a Monday meeting, EU energy ministers agreed to trigger a cap on the price of month-ahead natural gas futures on the Dutch Title Transfer Facility (TTF) – the bloc's benchmark gas exchange – to 180 euros ($191) per megawatt hour if it exceeds this level for more than three consecutive working days, media reported.

The cap can be triggered starting from February 15, 2023. The deal will be formally approved by countries in writing, after which it can enter into force. Once triggered, trades would not be permitted on the front-month, three-month and front-year TTF contracts at a price more than 35 euros/MWh above the reference LNG price, Reuters reported.

The EU has debated a gas price ceiling for a long time, and its goal has shifted from capping the price of Russian gas to reduce Moscow’s income from selling energy to ensuring that gas prices in the EU stay acceptable, Cui Hongjian, director of the Department of European Studies at the China Institute of International Studies, told the Global Times on Tuesday.

EU members diverged on whether to set the price ceiling. According to Reuters, Germany voted to support the deal but also raised concerns about the policy’s impact on Europe’s ability to attract gas supplies in the price-competitive global market. Hungary reportedly voted against the price cap and the Netherlands and Austria abstained.

Despite internal divisions, the EU agreed to the price restriction, highlighting the bloc’s growing concerns over future energy supply, Zhang Hong, an associate research fellow at the Institute of Russian, Eastern European and Central Asian Studies of the Chinese Academy of Social Sciences, told the Global Times.

The price ceiling is intended to cope with severe situations and cannot assist Europe in fundamentally resolving the energy shortage, said Zhang, noting that without Russian supplies, the EU will face a gas shortage of 30 billion cubic meters. The market determines the price of oil and natural gas, and when supply and demand are out of balance, intervention will have negative consequences.

Zhang noted that reacting to the EU's pushing of gas prices, producers may decide to shift gas sales to Asia, which is also not good news for the EU.

Analysts said that it seems that the EU has set several conditions to trigger the cap in order to make the mechanism “more reasonable,” including that the cap will also apply to three-month and year-ahead gas trades, and it will remain active for at least 20 working days once triggered.

Setting a price limit, on the other hand, is an unusual practice that violates market norms.

How gas producers and key purchasers would respond remains unknown, and that uncertainty in the gas market will grow as more complicated games may begin, Cui said.

Analysts believe that the EU's recent decision will also have an impact not just on Russia, but also on other producers such as Norway and other nations in North Africa and the Middle East.

Following the Russia-Ukraine crisis, the EU has accelerated its decoupling from Russia on energy supply, giving American energy firms the opportunity to make big profits, Zhang said.

Cui said that the EU has worked to reduce its reliance on Russia for energy – from the previous 40 percent to the current 7 percent, at the expense of enormous upheavals in its energy system. And to insure energy supply security, the EU has to purchase high-priced gas from the US.

The energy shortage may improve next year as the EU has signed long-term contracts with some suppliers in the Middle East and North Africa, Cui said, however, one dilemma for the EU is that although it can solve its energy supply difficulties in the short term, its manufacturing businesses and other energy-consuming industries may be unable to withstand the energy crisis and may opt to leave the EU, which will be a heavier blow to the EU's economy and development.

Europe got hit by roughly $1 trillion in surging energy costs since the Russia-Ukraine conflict, and the deepest crisis in decades is only getting started, Bloomberg reported, noting that after this winter, the region will have to refill its gas reserves with little to no deliveries from Russia, intensifying competition for fuel tankers.