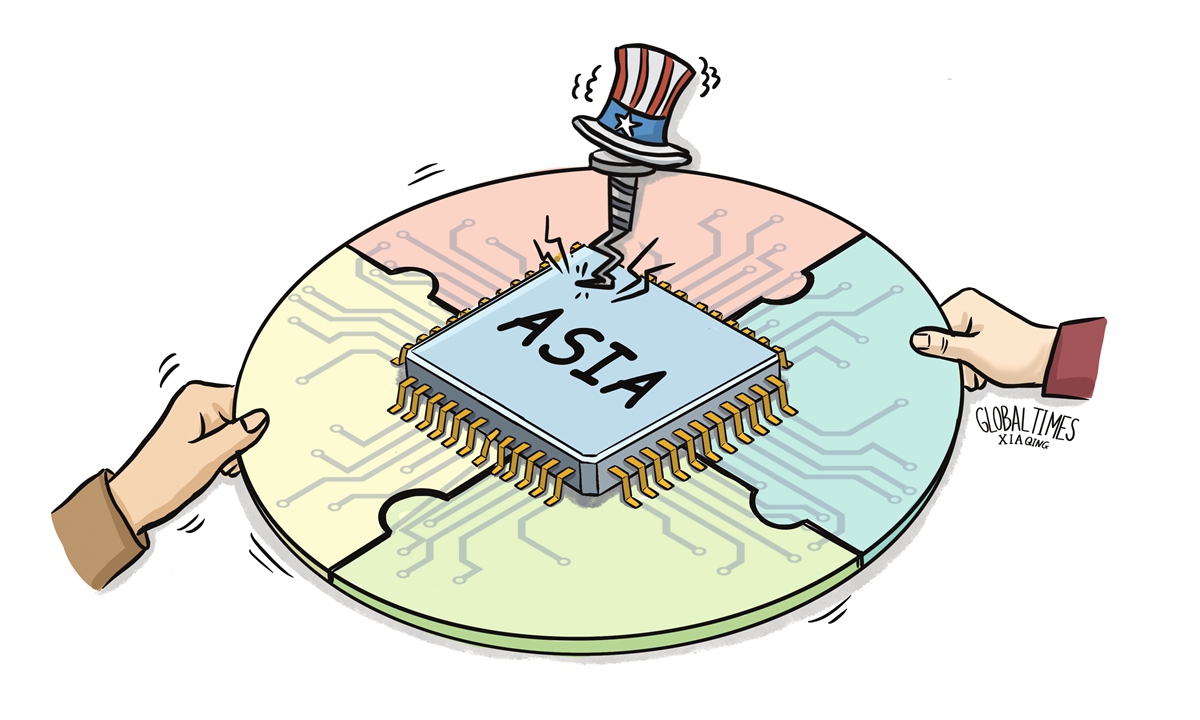

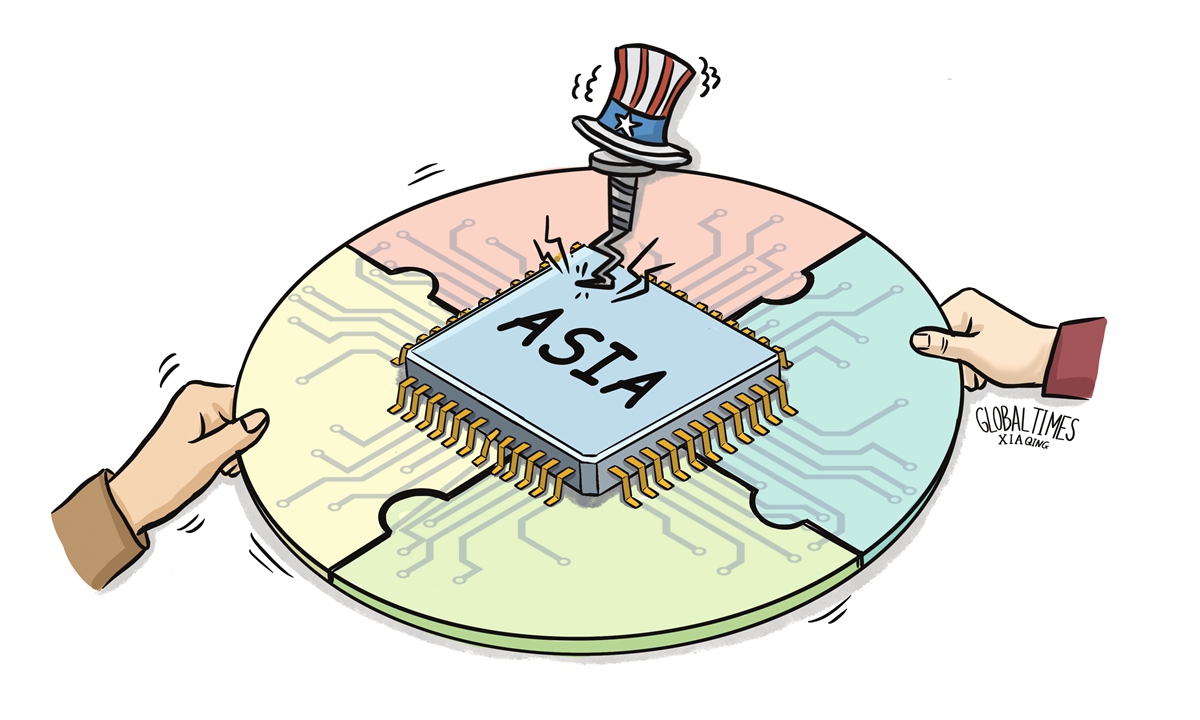

Illustration: Xia Qing/Global Times

Japanese Minister of Economy, Trade and Industry Yasutoshi Nishimura is set to visit the US from Thursday to discuss issues such as cutting-edge semiconductor technology cooperation as well as US restrictions on selling advanced chip technology to China, the Sankei newspaper reported on Tuesday. Many believe Nishimura's trip will pave the way for a summit between Japan's Prime Minister Fumio Kishida and US President Joe Biden which is scheduled to take place next week in Washington.

It is unclear whether semiconductor is a focus of Nishimura's upcoming trip to the US and how Japan will respond to Washington's export restriction push, but one thing is almost certain: the US appears ready to pressure Japan even more to ask Tokyo for coordination in stymieing China's efforts to develop high-end semiconductors, and Japan has a desire to enhance cooperation with the US and revitalize its semiconductor industry.

In May 2022, Kishida and Biden reaffirmed their intention to strengthen semiconductor-related cooperation. A document released by the two countries showed that they will work together with like-minded allies "in areas such as semiconductor manufacturing capacity, diversification, next-generation semiconductor research and development and responding to supply chain shortages," according to the Japan Times. There is a possibility that such ideology-based semiconductor cooperation will be enhanced during Nishimura's upcoming visit and the Kishida-Biden summit.

However, some politicians in Tokyo may perhaps be naive to count on US-Japan cooperation to revive the country's stalled semiconductor industry. Looking back at history, the last time the US launched a "semiconductor war" was against Japan in the 1980s. Japan was once a global leader in semiconductor manufacturing, but the US attack during the 1980s exacerbated the collapse of the Japanese semiconductor sector. It is hoped that Japan will not turn itself to cannon-fodder again in Washington's "semiconductor war" today.

Some statistics show Japan now accounts for only nine percent of the global semiconductor production. However, although no longer the world's largest semiconductor producer, Japan still maintains a high market share and international competitiveness in product groups such as sensors.

As Washington tries to persuade allies to join its China chip technology export ban, some Japanese political elites' obsession of playing geopolitical games has prompted the nation to work together with "like-minded allies" in semiconductor industries, but they must avoid hurting Japanese semiconductor enterprises' interests in the Chinese market. This is a dangerous balancing game, and if they go too far, the remaining advantages in the development of Japanese semiconductor sector will be exhausted.

Tokyo Electron is the largest semiconductor manufacturing equipment provider in Japan and the third largest in the world. Nikkei Asia reported in August that the company said it is "very concerned" about US moves to expand high-tech export curbs against China, a key market for the Japanese chip equipment maker. China is reportedly the biggest market for the firm in its last business year, with sales from the Chinese market accounting for 28.3 percent of the total.

China's vast market is of great significance for Tokyo Electron and other Japanese semiconductor companies that constitute the core competitiveness of the Japanese economy. When the US government enacted sweeping rules that aimed to cut off China from key chips and semiconductor manufacturing equipment, Japanese semiconductor companies may fall victim to US government bullying.

At the very least, the Japanese government should defend its semiconductor companies' legitimate rights and interests, otherwise, those firms will be exposed to bullying by the US government and suffer financial losses caused by Tokyo's compromise against US pressure.

High-tech trade is mutually beneficial to both China and Japan, and it involves the interests of many Japanese companies such as Tokyo Electron. Hopefully Japanese politicians can remember this forever, especially when they think about how to work together with "like-minded allies" in semiconductor areas and face pressure from the US government.