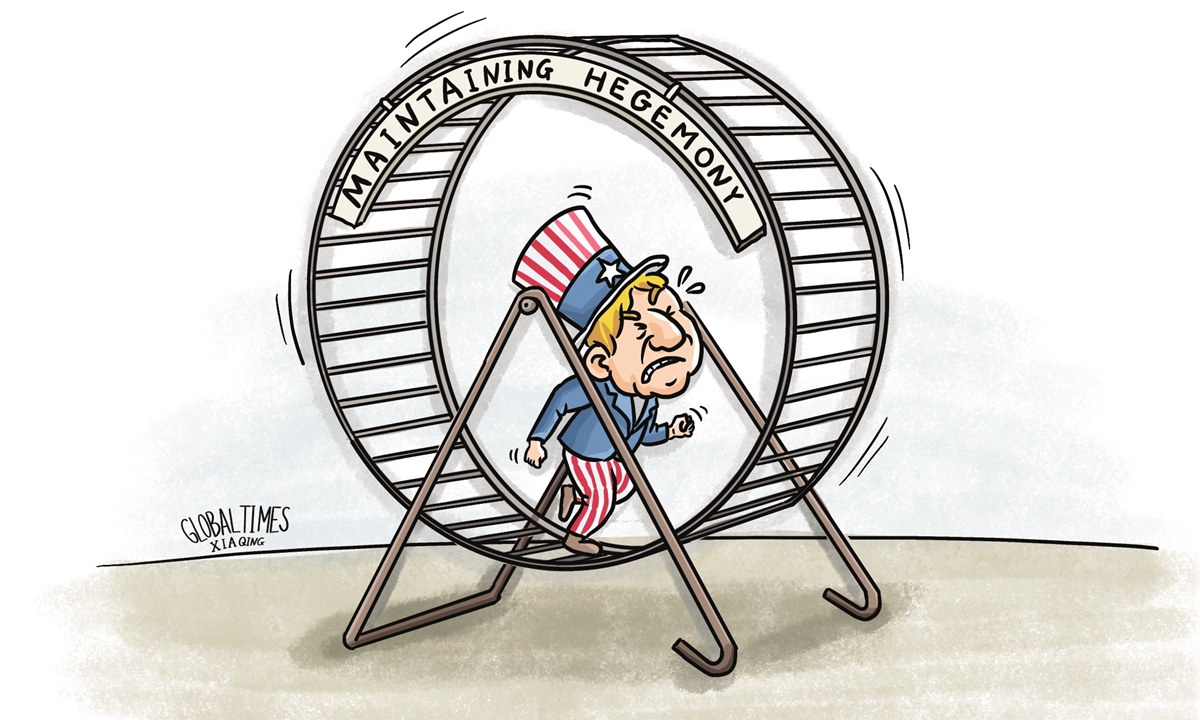

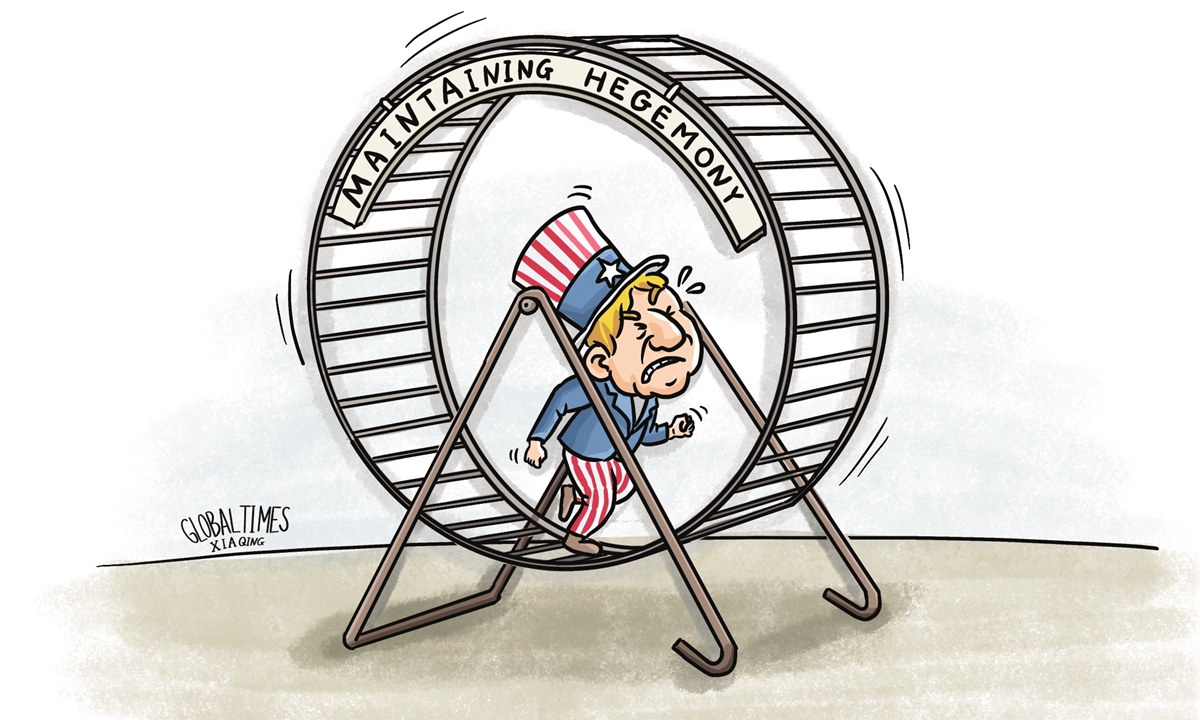

Illustration: Xia Qing/Global Times

There's a new viewpoint that's emerging in recent days that the US and its Western allies are uneasy about the prospects of a multipolar world. In fact, the US hardly recognizes this unavoidable fact while, at times, its European allies do pay some lip service to it. The US only has one viable option to combat this trend, with military force, which will inevitably weaken the US in every other sphere: economically, diplomatically, politically and in trade relations.

The reason that the US can only muster a military response is apparent: The US has the world's largest military budget and in the era since WWII has built up a global infrastructure to essentially police the world and its various trade routes. The lack of an interconnected Eurasia through land-based infrastructure has allowed the US to control the periphery of the so-called world island, where most of the world population and global wealth resides, with its navy.

However, for instance, the China-proposed Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) is beginning to connect Eurasia. This is precisely why the US is afraid of the BRI and why its media has launched relentless attacks on it, from drawing skepticism over its success to making charged claims of "Chinese imperialism."

The past week saw Japanese Prime Minister Fumio Kishida mount a five-country sojourn across Europe and North America, capped off with a summit with US President Joe Biden, and with a string of defense agreements signed. Now, Japan is planning to amass long-range missiles capable of attacking the Chinese mainland. It shows that the US and its allies are doing all they can to maintain their strategic position on the periphery of Eurasia.

But the US sees the all-important China-Russia strategic partnership, which spans most of the Eurasian continent, a significant threat to this. Various simulations have shown that the US would lose a war with both powers if it began a conflict with them at the same time, creating a serious simultaneity issue for Washington. That's why it is now trying to stagger competition by vigorously opposing Russia through the conflict in Ukraine while building up the infrastructure capable of containing China militarily.

But even if Russia's objectives in Ukraine weren't met, the modern battlefield is no longer fought with guns and tanks. It is, instead, fought through trade and economics. And that's why the US repeatedly uses unilateral sanctions as a measure to combat its geopolitical adversaries and impose its will on foes. We have seen, through the Ukraine conflict, that efforts to do so against Russia are unsuccessful. This translates to diminished US economic and trade power.

Given China's indispensable supply chains, watching this situation playout from the perspective of Beijing leaves one clear conclusion: In the event of such an outright conflict between the West and China, as it is happening with Moscow, the majority of the global community could not and would not join Western-led sanctions on Beijing. From this point of view, China has already won the most important realms of modern conflict and is in a far better position strategically than the US.

That being said, this does not imply that Beijing would naturally be the center of the new unipolar world order, essentially dethroning Washington as the new center of global power. Instead, it suggests that Beijing would be one of several power points in a multipolar world, though an important one.

With the continuing political integration of Africa, through the African Union; renewed calls for Latin American unity; breakthrough economic deals in the Middle East and the already-existing Arab League; the European Union and the continued eastward drift of the global financial center, this reveals where the new centers of power will be. That is, Latin America, Africa, Europe and Asia, and North America to a lesser degree.

Again, Washington's only option to resist this inevitably is through its military. And that is a prospect that fundamentally and irrecoverably endangers world peace. America's unipolar moment was brief; it was not unheard of in history but it was indeed a rarity. Multipolar eras, on the other hand, are far more often the norm. And given the postwar consensus embedded in the Charter of the United Nations, the emerging multipolar world would be far more peaceful than any other that preceded it if it holds true to its agreed-upon values.

The author is a Prague-based American journalist, columnist and political commentator. opinion@globaltimes.com.cn