Illustration: Xia Qing/Global Times

On July 1, 1987, a group of US lawmakers staged one of the most iconic "Japan-bashing" acts during the height of the US-Japan trade war. Blasting Japanese electronics giant Toshiba for allegedly selling high-tech machinery to the Soviet Union, the US lawmakers smashed one of the firm's radios with a sledgehammer. Besides the allegation of selling advanced milling machines and computer programs to the Soviet Union, Toshiba, being at the forefront of Japan's world-leading semiconductor industry at the time, had already drew the ire of US politicians and industry competitors.In fact, a year prior to the sledgehammer incident, in August 1986, the US government practically forced Japan into signing a semiconductor agreement, under which Tokyo made huge concessions, including limiting sales of Japanese chips in the US market, increasing the share of US chips in the Japanese market and allowing the US government to intervene in the pricing of Japanese chips. Such concessions directly led to the downfall of the Japanese semiconductor over the past several decades. Japan made more than half of the global supply of semiconductors in the 1980s, but its global market share has fallen under 10 percent in recent years.

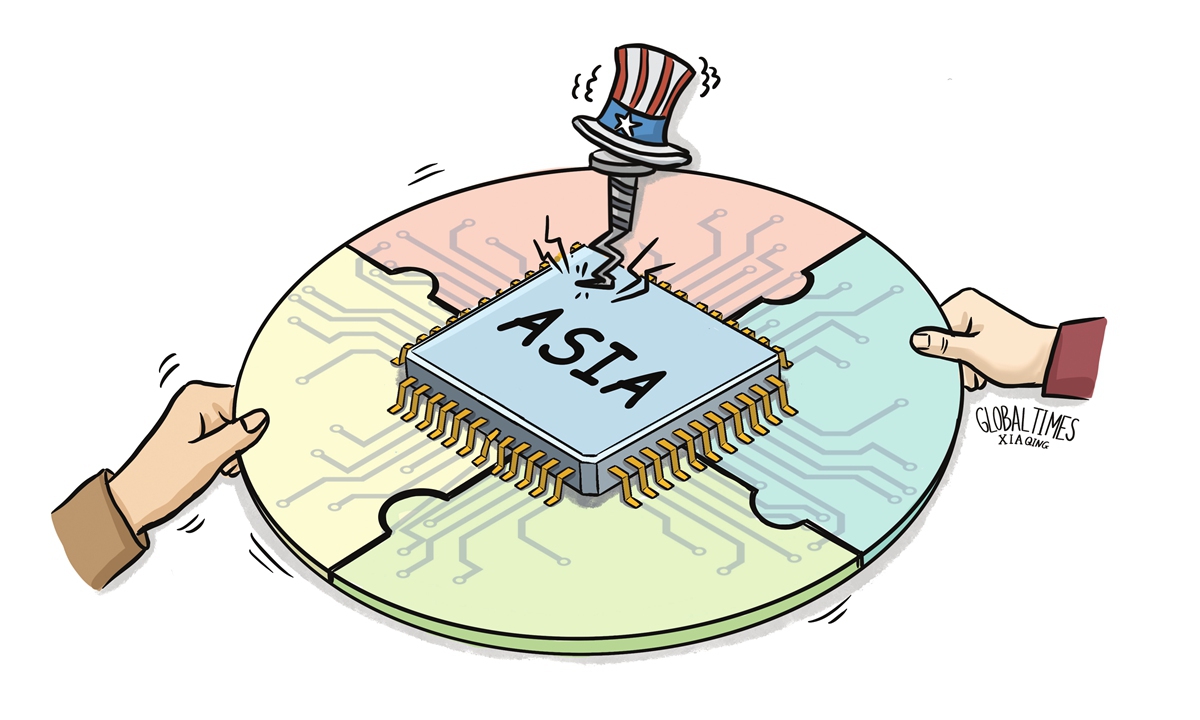

Nearly 40 years after that fateful agreement, Japan's semiconductor industry has once again attracted attention from US politicians. This time around though, Washington wants Japan to carry out its order of implementing the US' chip ban against China. As its sweeping export restrictions on shipments of chipmaking tools to China imposed in October 2022 has so far shown no real effect, Washington has recently stepped up pressure on allies like Japan, the Netherland and South Korea - all major exporters of chipmaking equipment - to carry out the ban at its behest. Evidently, the move has put the three major suppliers in a huge dilemma. They have a tough time saying no to Washington, but bowing to Washington's pressure could mean massive economic losses.

But just like how it faltered embarrassingly under US pressure in the 1980s, Tokyo appears to be on its knees again amid the latest round of US pressure. Last week, media reports suggested that Japan and the Netherlands had reached an agreement with the US to join the latter's ban against China. Despite the stream of media reports, details, especially official details, about the supposed deal have been scarce. Then on Saturday, Japanese media reports not only confirmed that Japan will carry out the US ban but also how it will do so. According to Kyodo News, Japan will change its foreign exchange law in order to implement the US' ban. Let this sink in again: a sovereign country - the world's third-largest economy, no less - has to change its domestic laws just to follow orders from another country to target a third-party country.

Alas, Tokyo's eagerness to cling to Washington's apron strings has not and will unlikely change regardless of the profound humiliation and incalculable losses the country and its people suffered over the past several decades. No doubt such seemingly absolute obedience will cost Japan's semiconductor industry and its economy dearly going forward.

Increasingly feeling the pain of its shrinking semiconductor industry, the Japanese government has in recent years, especially after the COVID-19 pandemic, announced a series of measures to rebuild its chip industry. In December 2022, Japan passed a supplementary budget package, which features 1.3 trillion yen ($10 billion) for semiconductors. That includes funding for a new plant of the Taiwan island-based chipmaker TSMC in Japan. The Japanese government wooed TSMC with a subsidy of up to 476 billion yen ($3.6 billion), said to be the largest ever single payment to a factory project. The Japanese government has also backed chip venture Rapidus with 70 billion yen in seed capital. The venture needs about 7 trillion yen of mostly taxpayer money to begin mass production of advanced chips in around 2027, Reuters reported.

All these efforts could go to waste, if Tokyo does not play its cards right - or to put it in blunter terms, if Tokyo carries out US orders at all costs. For starters, Tokyo's ambitious plan to revive its semiconductor industry in itself may be a little too ambitious. Despite demand from its sizable automobile industry and technological advantages in certain areas such as optical sensors and materials, Japan has neither the complete industrial chain to make chips independently or a market big enough to consume all the chips it aims to produce. In fact, no country alone, whether it's the US or Japan or South Korea - or even a US-led chip alliance of several major chip producers - can hold monopoly on the global supply chain.

Moreover, though Japanese politicians like to hype "risks posed by China," the real threat to Japan's semiconductor industry is from other major chip producers like South Korea and the US. While the US is seeking to form a chip alliance against China, its protectionist policies to revive its own domestic semiconductor industry is unleashing a chip war among its allies with all adopting protectionist policies to bolster their own domestic industries. The US' CHIPS and Science Act passed in late 2022 offers 25-percent tax credits for new chip investment in the US and about $50 billion in additional public investment. That has raised concerns for a "hollowing-out" of the semiconductor industries in many countries and regions, including South Korea and Japan, regardless of their own efforts.

Still, for Japan's semiconductor industry, the biggest threat is the Japanese government's tendency to bow to US pressure. Even if Japan's plan to revive its semiconductor industry by some miracle actually succeeds, does any Japanese politician actually believe Washington will sit idle and let it thrive? Is Tokyo prepared to give up its entire semiconductor industry again at the order of the US, as it did in 1986? If so, what's the point for its rebuilding efforts?

The author is a reporter with the Global Times. bizopinion@globaltimes.com.cn