Illustration: Chen Xia/GT

The Kingdom of Bhutan is located on the southern slopes of the eastern Himalayas and situated between China and India. It has maintained close political, economic, cultural and religious ties with Xizang for a long time throughout history. In the middle and late 18th century, Britain began to invade Bhutan. From the end of the 19th century to the beginning of the 20th century, Britain forced Bhutan to sign a series of unequal treaties, bringing Bhutan under the "protection" of Britain, which gradually disintegrated the suzerain-vassal relationship between Xizang of China and Bhutan. After independence, India insisted on inheriting the colonial legacy of the British Empire and established an unequal "special relationship" with Bhutan, controlling Bhutan's national defense and economy, while interfering in Bhutan's internal affairs and foreign affairs by various means.1. "Special relationship" is the basis for India's control over Bhutan

The so-called special relationship between India and Bhutan is the political basis of India's control over the country. It stems from India's insistence on inheriting the colonial heritage of the British Empire and India's concept of regional hegemony, and takes the unequal treaties signed by the two countries as the legal basis.

The British colonists continued to erode Bhutan's national sovereignty. In the late 18th century, in order to open up trade routes to Central Asia and the Chinese mainland and weaken China's influence in the southern foothills of the Himalayas, Britain began to infiltrate and invade kingdoms such as Nepal, Sikkim and Bhutan. In 1772, a British Expeditionary Force captured Bhutan-controlled Cooch Behar. In 1773, the British Expeditionary Force invaded Bhutan. On April 25, 1774, Bhutan signed a so-called peace treaty with the British East India Company. Bhutan agreed to return to its pre-1730 boundaries, and pay Britain a symbolic tribute of five horses a year and allow the British to harvest timber in Bhutan. In 1826, the British annexed Lower Assam, and Britain-Bhutan relations began to become tense. From 1834 to 1835, the British invaded Bhutan, and Bhutan lost part of its territory.

In 1841, Britain annexed Assam Duars, a tea-producing region controlled by Bhutan. In 1842, Britain took control of the Bhutanese-administered Bengal Duars. From 1864 to 1865, Britain launched the Duar War. Bhutan was defeated and signed the Sinchula Treaty. Bhutan ceded Assam Durs and Bengal Duars, as well as the 83 square kilometers of territory around Dewangiri in its southeastern part.

To ensure the safety of the northern part of the British India, Britain signed the Treaty of Punakha with Bhutan in January 1910. According to the treaty, Britain guaranteed Bhutan's independence, gave the Royal Government of Bhutan more subsidies, and controlled Bhutan's foreign relations. According to Leo E. Rose of the University of California, Berkeley, this treaty began the practice of delegating Bhutanese foreign relations to another suzerain, the treaty also affirmed Bhutanese independence as one of the few Asian kingdoms never conquered by a regional or colonial power.

India insisted on inheriting the British colonial heritage and established the "special relationship" between India and Bhutan. After independence, India pursued hegemonism in South Asia, inherited the Bhutan policy of British India, and established the so-called "special relationship" between India and Bhutan. On August 8, 1949, India and Bhutan signed the Treaty of Friendship between India and Bhutan. Article 2 of the treaty stated, "The Government of India undertakes to exercise no interference in the internal administration of Bhutan. On its part the Government of Bhutan agrees to be guided by the advice of the Government of India in regard to its external relations." On February 8, 2007, Britain and Bhutan amended the treaty and signed the India-Bhutan Treaty of Friendship. The new treaty deletes the provision that Bhutan should be guided by the advice of the Indian government in regard to its external relations, and adds content to consolidate and expand cooperation in the fields of economy, culture and education between the two countries. It should be said that the India-Bhutan treaty in 2007 allowed Bhutan to resume part of its sovereignty and gain greater autonomy, but it did not change the foundation and situation of India's control of Bhutan.

In this regard, academia generally regards the India-Bhutan Treaty as a continuation of India's policy toward Bhutan during the British colonial rule. According to T. T. Poulose of the University of Delhi, "It is true that India inherited the British Treaties with Bhutan and that she decided to continue substantially the same relationship with Bhutan as before." T. K. Roy Chowdhury of the University of North Bengal advanced, "This accord was partly in keeping with the spirit of Bhutan's relations with British India - enshrined in the Treaty of Sinchula in 1865 and renewed in the Treaty of 1910." Joseph C. Mathew of the University of Azad Jammu & Kashmir said, "This treaty is a refined version of the treaties signed between British India and Bhutan in 1774, in 1865 and in 1910."

There is no basis for pinning the blame on China for the Bhutan policy of the UK and India. Indian scholars generally believe that the series of treaties signed by Britain or post-independence India with Bhutan and the establishment of a "protection relationship" or "special relationship" aim to deal with China's territorial claims to Bhutan. For example, Chowdhury believes that "India's main aim was to keep Bhutan free from the power politics which China's policy to absorb Tibet entailed." However, this view does not conform to the facts.

When British India signed treaties with Bhutan in 1865 and 1910, China was facing the onslaught of Western powers during the Qing Dynasty (1644-1911) and the collapse of the late Qing regime respectively. The central government's ability to govern Xizang was severely weakened, and it was impossible for China to pay attention to Bhutan, which once submitted itself to the rule of Xizang. When India and Bhutan signed the treaty in 1949, the People's Republic of China had not yet been established. It is illogical to explain India's actions in 1949 with the historical facts of the peaceful liberation of Xizang in the 1950s. In addition, the views of some Indian scholars have also denied the above-mentioned views from different angles.

For example, Poulose interpreted the behavior of Britain and India from the perspective of national interests, arguing that "The treaty carefully preserved the essence of the British policy, namely safeguarding the vital national interest of India." Nitasha Kaul from the University of Westminster focused on economic needs, arguing that "the British involvement in India was driven by an economic imperative, and much of the territorial and political aggrandizement during the late eighteenth century and throughout the nineteenth century has to be understood as resulting significantly from this… The specific nature of the imperial economic imperative shifted, from one in which commercial interests were paramount in determining the Company's attitude toward Bhutan in the late eighteenth century, to the ascendance of production interests in which fertile territories were brought under control for the plantation economy in the late nineteenth century, to one in which overwhelming economic dominance was a tool to keep Bhutan firmly aligned with India in the twentieth century." Therefore, the narratives of Indian officials and scholars about the relationship between India and Bhutan are one-sided statements that aim to confuse the public.

2. India's security and economic control over Bhutan

The India-Bhutan Treaty provided the basis for India to control Bhutan, and the so-called special relationship led India to consider itself the "protector" of Bhutan. India's control and influence over Bhutan are first reflected in the security and economic fields.

India is deeply involved in Bhutan's national defense and military construction. India saw Bhutan as a buffer between China and India and included Bhutan in its national defense strategy due to Bhutan's strategic location adjacent to the Indian states of West Bengal and Assam, as well as bordering China's Xizang and what was then East Pakistan (now Bangladesh). On August 28, 1959, then-Indian prime minister Jawaharlal Nehru stated in the Lok Sabha that "the defense of the territorial uprightness and frontiers of Bhutan was the responsibility of the government of India." Although the 1949 treaty contained no such clause, India unilaterally declared itself the "protector" of Bhutan. Nehru stated in the Parliament of India in November 1959 that "any invasion against Bhutan… shall be considered an invasion against India."

After the Tibetan nobles rebelled, India tightened its control over Bhutan, building strategic roads in Bhutan and increasing its "aid" to Bhutan. In 1962, when the situation on the China-India border deteriorated, India took the opportunity to deploy troops in Bhutan. The equipment used by the Bhutanese army came from India. Bhutan's defense plan was formulated by Indian military experts.

India has always maintained its position as Bhutan's largest aid donor. The budget of Bhutan's first Five-Year Plan (1961-66) stood at $13 million, and all the money was provided by India. The second Five-Year Plan (1966-71) with an outlay of $25 million was also entirely funded by India. Bhutan drew up its third Five-Year Plan (1971-76) jointly with the Planning Commission of India, with an allocation of $43.75 million, entirely provided by India. The fourth Five-Year Plan (1976-81) cost at $110 million, of which India paid 90 percent. The fifth Five-Year Plan (1981-86) reached $330.5 million, three-fourths of which was borne by India.

Bhutan has actually received a total of $4.7 billion in aid from India from 2000 to 2017, making it the top recipient of Indian aid in South Asia. In December 2018, Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi announced a Rs 4,500 crore financial assistance to Bhutan for its 12th five-year plan (2018-23). The significant proportion of aid has forced Bhutan to consider India's interests and feelings in both domestic and foreign affairs.

India is Bhutan's only transit trade channel and most important trading partner. Due to the absence of diplomatic relations between China and Bhutan, economic and trade relations have become an important means for India to influence Bhutan's policies. The India-Bhutan Agreement on Trade, Commerce and Transit, which was first signed in 1972, provided for duty-free transit of Bhutanese exports to third countries. The agreement has been revised five times since then, establishing a free trade system between the two countries.

In addition, India is Bhutan's most important trading partner both as a source and market for its trading goods and commerce. Since 2014, India's trade with Bhutan has almost tripled from $484 million in 2014-15 to $1.42 billion in 2021-22, accounting for about 80 percent of Bhutan's overall trade. India has a significant trade surplus in India-Bhutan trade, with trade surpluses of $184 million, $188 million, $201 million, $168 million, $286 million, $334 million, $305 million, and $332 million from 2014 to 2022, respectively.

Additionally, India controls Bhutan's most important source of revenue, the hydropower industry. On the one hand, India has moved away from the initial 60:40 model (60 percent grant and 40 percent loan) to a 30:70 model (30 percent grant and 70 percent loan). This change has led to Bhutan's serious debt, and also deepened Bhutan's economic dependence on India. On the other hand, a significant portion of Bhutan's hydropower has been exported to India, constituting about one-fourth of the country's GDP.

3. Indian interference in Bhutan's internal affairs and foreign policy

India controls Bhutan's security and economic lifelines, which enables it to interfere in Bhutan's internal affairs and foreign policy, highlighting India's regional hegemony in its policy toward Bhutan.

India frequently interferes in Bhutan's internal affairs by virtue of its absolute control over Bhutan in the spheres of security and the economy. On the one hand, New Delhi pressures Bhutan to crack down on cross-border militancy within its borders. After the end of the Cold War, some of the northeast Indian insurgent groups fled to Bhutan and initially set up camps mainly in the Samdrup Jongkhar District. The United Liberation Front of Asom (ULFA) and the National Democratic Front of Bodoland (NDFB) then exploited these camps in Bhutan to launch guerrilla warfare in the Indian state of Assam. After being hit by the Indian government forces, they withdrew to their camps in Bhutan.

Since these armed groups did not pose a threat to the safety of the Bhutanese people, the Bhutanese government was not particularly concerned about the presence of these armed groups in its territory. The Indian government repeatedly demanded that Bhutan conduct joint strikes with India to crack down on the cross-border armed groups, but Bhutan was relatively inactive in responding to this initiative.

Under India's constant pressure, the Bhutanese government agreed in 1998 to negotiate with the leaders of ULFA and NDFB, hoping that they would gradually reduce their camps in Bhutan and eventually leave the country. On December 15, 2003, Bhutan launched an attack codenamed "Operation All Clear" on the armed group's camps in southern Bhutan with 6,000 troops.

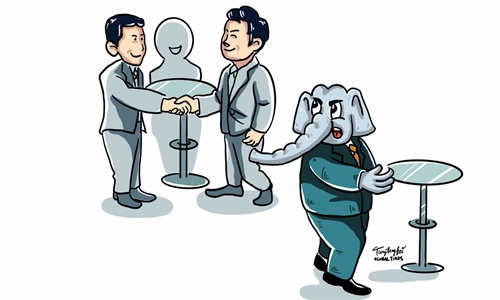

On the other hand, India meddled with Bhutan's election to prevent a pro-China party from coming to power. On July 13, 2013, People's Democratic Party (PDP), the opposition party, won the second-ever parliamentary election in Bhutan, beating the ruling party - Druk Phuensum Tshogpa (DPT) - with a surprising margin.

However, in the first round of voting a month and a half earlier, the ruling party, which was considered friendly to China, held a clear lead. The reason for this unexpected result lies in that India had interfered in the Bhutanese election by using the tool of "economic assistance" just before voting. India suddenly announced to stop supplying subsidized gas and kerosene to Bhutan and canceled price subsidies for imported electricity from Bhutan's Chukha hydroelectric power station.

India controls Bhutan's foreign policy through various means. On the one hand, India limits Bhutan's establishment of diplomatic relations with other countries. Although India has repeatedly stated that Bhutan is an independent sovereign country, it remains very vigilant about Bhutan's development of foreign relations and even opposes Bhutan's contacts with other countries.

So far, only over 50 countries have diplomatic relations with Bhutan, and only India, Bangladesh, and Kuwait have embassies in Bhutan. India continues to suppress Bhutan and hinder its efforts to establish diplomatic relations with China. Bhutan has not even established formal diplomatic relations with any of the five permanent members of the United Nations Security Council. Neville Maxwell, an Australian-British journalist, stated in an interview with Ashok Kantha, India's former ambassador to China, that "Bhutan has not been allowed to open formal diplomatic relations with the PRC, and that years of border negotiations with China have never moved beyond stalemate can only reflect India's inhibitory, undeclared control of Bhutan's approach."

On the other hand, New Delhi interferes in the China-Bhutan border negotiations. China has resolved most of its land border issues through negotiations since the 1950s, but does not complete its border talks with Bhutan because India insists on representing Bhutan in the negotiations, while China hopes to directly engage with Bhutan.

The author is an associate research fellow with the National Institute of International Strategy at the Chinese Academy of Social Sciences. opinion@globaltimes.com.cn