Japan's treating oceans as a radioactive waste dump a 19th-century approach: nuclear expert

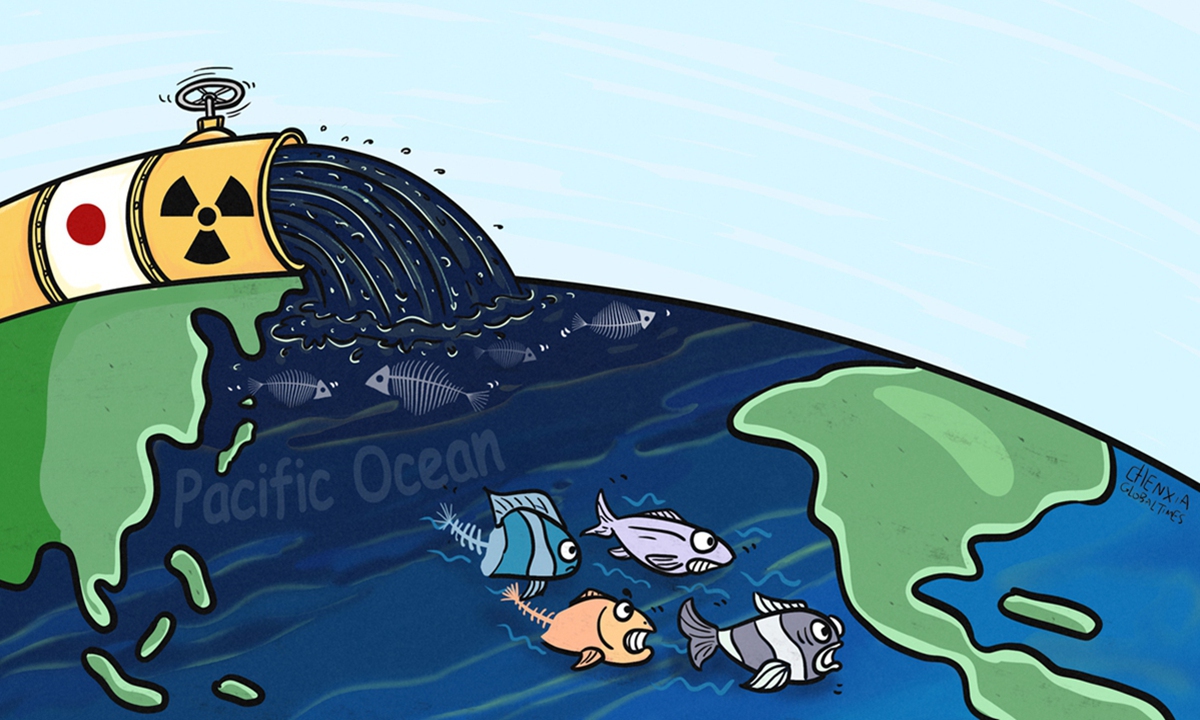

Illustration: Chen Xia/GT

Editor's Note:

Japan's plan to dump nuclear-contaminated wastewater into the ocean has been strongly condemned by the international community. Nonetheless, Tokyo is still going its own way and speeding up the plan to make the rest of the world pay for it. What harm will Japan's action bring in terms of the environment and international relations? What should relevant parties do to prevent the selfish act of Japan?

"This is 19th-century approach to pollution - out of sight, out of mind - dilution is the solution to pollution," said Melbourne-based Tilman Ruff (Ruff), co-president of International Physicians for the Prevention of Nuclear War (Nobel Peace Laureate 1985) and co-founder and founding international and Australian chair of the International Campaign to Abolish Nuclear Weapons (Nobel Peace Laureate 2017), in an interview with Global Times (GT) reporter Wang Wenwen. Treating the oceans as a radioactive waste dump belongs to a past distant century, said Ruff.

This is the second piece of the series.

GT: From the nuclear perspective, what harm does Japan's dumping of nuclear-contaminated wastewater pose to the environment?

Ruff: Radioactivity, once let loose in the environment, cannot be contained. It travels with the wind and the water, and the currents and with organisms, indiscriminately across all borders and for extremely long distances. For example, after the Fukushima nuclear disaster first happened in March 2011, within one year, there were contaminated tuna that were containing cesium fallout from Fukushima that were caught off the coast of California.

Also, fish swim. Predatory big fish travel very long distances as do sea birds, turtles, sharks and sea mammals like whales and dolphins. This radioactivity with many different isotopes that behave in all sorts of different ways chemically and biologically disperses in the water. Also some are concentrated up the food chain, particularly some biologically important ones like Cesium and strontium. So at the top of the food chain in fish like tuna, the concentrations can be thousands of times higher than in the water that the plankton at the bottom of the food chain concentrated the material from in the first place.

With radiation, we know that every little bit extra is harmful. There's no level that you can say, if you only get this much, it's fine, no harm. It increases our long-term risk of cancer, heart attacks and strokes and some other chronic diseases. Women and girls, and particularly children, are much more susceptible to the same dose of radiation. We should minimize the amount of additional radiation in the environment as much as possible.

GT: Instead of directly dumping the water into the ocean, does Japan have other options?

Ruff: A number of scientific experts and civil society groups have suggested quite feasible ways in which this water could be managed without the trans-boundary, trans-generational effects that would extend out of control way beyond Japan.

The first and probably the simplest would be to simply build large seismically safe tanks. There are more than 1,000 tanks that are on the site now, containing 1.32 million cubic meters of contaminated water. Those are not designed for long-term secure, seismically safe storage. They're not properly welded. They leak. They were put together very quickly in an emergency context.

Japan has experience of building large, long-term seismically safe tanks. It has such tanks for its long-term fuel storage facilities as its national reserve. So such seismically safe tanks could be built, and many of the isotopes will decay over time, and some of them reasonably quickly. Tritium, for example, which has been discussed most often on the Japanese side, has a half-life of about 12 years. So every 12 years, the amount of tritium was reduced by half. In 12 years, you have half as much as you started with. In 24 years, you have 1/4 as much as you started with. So it reduces rather quickly. So if the water was simply stored for 50, 60, 70 years, and then released, it would be much less radioactive.

Another alternative would be either with or without purification, preferably with, this contaminated water could be used to make concrete that is used for structural applications. For example, foundations for roads and bridges, buildings, large infrastructure projects where it won't come into contact with people or other animals. Much of the harmful radiation, the beta radiation, would not be released from the concrete. It would be trapped within the concrete, even if the concrete is subsequently broken up. An industrial country like Japan goes through a lot of concrete for structural purposes.

There have been proposals to evaporate the water without taking the isotopes with it as a way of reducing the volume that could be combined with a storage option. Various combinations of those options could be an effective way of removing all of the risk of trans-boundary, trans-generational, out-of-control radioactive pollution. And those options haven't been adequately considered by either TEPCO or the Japanese government.

They haven't really given a detailed explanation. Any explanation that they give is, frankly, not really plausible or credible. This is a 19th-century approach to pollution - out of sight, out of mind - dilution is the solution to pollution, and there are many unfortunate precedents in most nuclear facilities around the world.

But it's really the cheapest and dirtiest solution. Unfortunately, in the management of the Fukushima disaster, there is a long history of decisions being made not in the best interest of either public health or environmental health. For me, the worst example of that was the arbitrary 20-fold increase in the radiation protection standard that Japan initiated within a month of the disaster to reduce the cost of relocation and compensation, which persists with no plan to bring it back down.

Unfortunately, bad decisions continue to follow one after the other. I can't justify or explain this decision. In this modern era, we really should not be treating the oceans - our common, shared cultural, biological, economic heritage - as a radioactive waste dump. It really belongs to a past distant century.

GT: How will Japan's decision affect its international image?

Ruff: There has been very strong and consistent criticism of this proposal from the government and scientific organizations in China, from the government of South Korea, from almost all Pacific island nations and the Pacific Islands Forum, from multiple UN Special Rapporteurs and many civil society organisations around the world. The Japanese foreign minister in March made a tour of a number of Pacific island countries, clearly in part to try and reassure nations that this plan is okay and won't cause them long-term harm, which I think many of them will be singularly unconvinced by.

In the Pacific, there is a very bitter memory. And it's not a past one. It's still an ongoing memory and experience of the legacy of more than 310 nuclear test explosions that France, Britain and the US imposed on Pacific jurisdictions with great cost to the health and wellbeing of the people of the Pacific. This plan runs contrary to previous commitments that the Japanese government at the highest level has made for decades. In 1985, then Japanese prime minister committed Japan not to engage in radioactive waste dumping in the Pacific. Prime Minister Fumio Kishida previously said that Japan would respect evidence-based respectful international consultation processes in consideration of this issue. That doesn't seem to have happened.

There is a real sense that, I think, particularly among Pacific island nations, that Japan is not living up to its promises. It is certainly acting contrary to the spirit of the South Pacific Nuclear Free Zone. It's the only nuclear free zone in the world, which is not called a nuclear weapons free zone. The intention was much broader. There are commitments that Japan has made that are really being contravened and not respected. This can only harm Japan's international image.

GT: Your letters to the relevant Australian federal ministers on this matter have gone unanswered for a couple of weeks, and no evidence is publicly available that the Australian government has supported Pacific neighbors in raising concerns about the planned discharge with its Japanese counterparts. Why is this the case?

Ruff: I can't answer that question. They haven't responded yet. I don't understand it because Australia has made a commendable and serious effort since the new government was elected in May last year to engage on a much more meaningful basis in a much more real partnership with Pacific island neighbors. We have a government that at least is half serious about addressing climate change compared with the previous government, which was clearly not serious about addressing climate change at all. And climate change is clearly the major long-term, political security, health, sustainability, economic issue that is front of center for all Pacific island nations who are bearing the brunt of the consequences that are already upon us.

But there's been a much more serious attempt to engage with Pacific neighbors on a partnership basis, rather than a sort of paternalistic big brother basis. If Australia were really serious about that, then we should express our concern to the Japanese government about this plan. Now is a critical time because the pipeline to discharge this water is well under construction. It's due to be completed in June. I hope that raising this issue more broadly now will help encourage governments to share these concerns with Japan and really encourage them to reconsider course. This program could be stopped at any time, even after it's commenced.

GT: Do you think the inaction of Australia, as well as the US and the West, have anything to do with politics?

Ruff: I'm sure it has everything to do with politics, but I can't speculate too much about why. But for the US and other states that discharge large amounts of radioactive material into the environment from their nuclear facilities, maybe they don't want to shine too strong a light on their own practices by raising concerns about this.

In Australia's case, it's hard to understand why. Japan is our close trading partner. There have been many joint initiatives. There's a lot of cultural contact. It's hard to understand why this friendship couldn't withstand honest concerns being raised on such an important environmental issue for the region.

GT: Your organization, International Physicians for the Prevention of Nuclear War, won the Nobel Peace Prize in 1985. From the perspective of peace, how will Japan's moves affect world peace?

Ruff: I think it's an important question. Peaceful relations are not just about military, non aggression and avoiding war, but it's about constructive, positive collaboration on shared concerns and issues in a way that the actions of one country don't disadvantage the people and the environment of other countries. So all of the big global problems, nuclear weapons, risks of war, pandemics, inequity, and poverty, environmental pollution, and the massive problem of global heating require cooperative solutions - they can only be solved together.

These issues are fundamentally peace issues. This kind of unilateral action by one government that has trans-boundary and trans-generational harmful consequences for a wide range of other nations right across the Pacific is not conducive to peaceful, constructive relationships and building the safe, healthy future we all desperately need.