Frequent officials’ visits between US, India cannot fundamentally change conflicting visions of world order

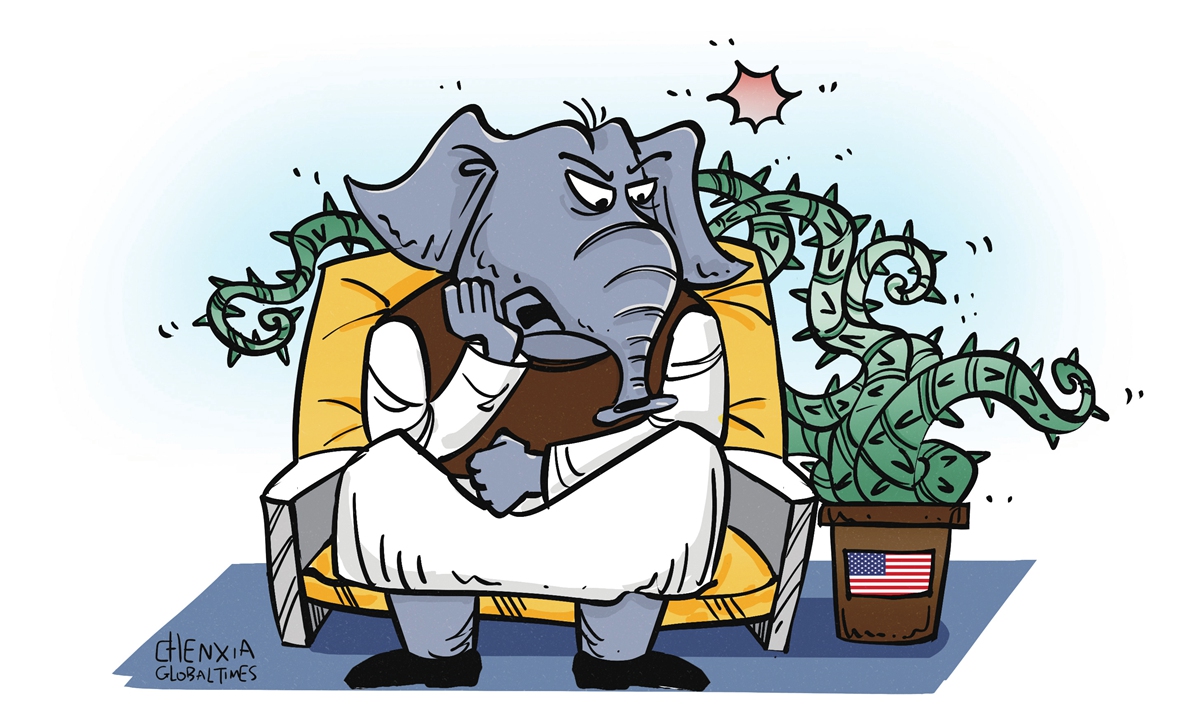

Illustration: Chen Xia/GT

US Secretary of Defense Lloyd J. Austin III kicked off his visit to India on Sunday to discuss ways to further expand the bilateral strategic engagement. Prior to his visit, a US Congressional Committee recommended the inclusion of India in "NATO Plus." Austin is expected to discuss a range of defense cooperation projects that are set to be unveiled after Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi's trip to the US later on June 22. During Modi's trip, US President Joe Biden will host the Indian Prime Minister for State Dinner, the third formal state dinner of Biden's presidency, a gesture of showing his emphasis on US-India relations.The frequent high-ranking official exchanges between India and US demonstrate that both countries are keen to develop their ties, particularly in light of their shared concerns about China. However, India's divergent approaches to handling the Ukraine crisis have somewhat overshadowed this. Earlier this year, the G20 Finance Ministers' meeting and G20 Foreign Ministers' meeting unveiled the dissatisfaction of the US and its allies against India's consistent support for Russia despite their staunch opposition. With a high-profile arrangement to receive Modi, Biden will make another attempt to woo India.

But a suspicious India is warier of a series of warning signs from the US and its allies. Last September, the US' decision to provide a sustenance package for Pakistan's fleet of F-16 fighter aircraft alarmed India and reminded the latter's bitter memory of the notorious Indo-Pak hyphenation practices by the US. Indian officials believed it was as an act of US to punish India's unwavering refusal to sanction Russia.

Earlier this year, a BBC documentary titled "India: the Modi Question" reexamined the role played by the Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi during sectarian riots in 2002 when he was the chief minister of Gujrat. The Indian government reacted by raiding the British broadcaster's office in New Delhi.

India also believes that despite their warming ties, the US is intervening in its domestic affairs. In March, the US Commission on International Religious Freedom criticized India's religious freedom conditions, saying they have taken a drastic turn downward since Narendra Modi took power in 2014. The US State Department also slammed India on human rights practices in its annual report. Modi had to enter the debate and declare that India is indeed "the mother of democracy" at the Summit for Democracy.

Bearing in mind their differences, a Financial Times article reminds the world that India will never be America's ally and that the West's assumption that India shares the same worldview is essentially wrong. It further argues that a proud India neither wants to see China's rise nor continuous hegemony by the US, and does not want to be part of either camp.

US scholar Ashley Tellies is one of the architects in assisting India to develop its overall capacity with US help to be a capable state to balance China in the region, hence designing a roadmap of the US-India alliance. But he recently admitted that the US had made a bad bet on India and the latter won't side with the US against China in a potential conflict. He further argued that the US is systematically exploited when India asks for concrete benefits from the US, but is reluctant to give strategic favors in return.

In response to Tellies' article, Ram Madhav, former BJP general secretary, criticized the West's assumption that India's rise is a result of the US' benevolence and argued that India's defense acquisition of "high-tech weapon systems from America not as a charity but against payment." Madhav further proudly asserted that India plays an important role in a multipolar world, and the US should respect India's primacy in the region.

A determined US aims to wrap a dominant share in India's defense imports, but the differences between them are both ideological and structural. Austin's trip to India happens in the context of the successful penetration of US firms into the Indian defense market, and the bilateral cooperation in the defense section becomes a symbol of the level of their ties in recent years. But Austin's trip and the forthcoming leaders' meeting won't fundamentally change their conflicting visions of world order.

Now the choice is Biden's. On the one hand, he is trying all means to woo India's support to contain China and thus maintain US hegemony. On the other hand, the consideration of India is equal to that of the US. This might be the dilemma a declining hegemon has to face, giving all out to contain a rising power by relying on its allies and at the same time preserving its boss style in front of other major powers.

The author is an associate professor at the Institute of International Studies, Fudan University. opinion@globaltimes.com.cn