Humanity cannot afford to aggravate the toxification of the planet: UN special rapporteur

Illustration: Chen Xia/GT

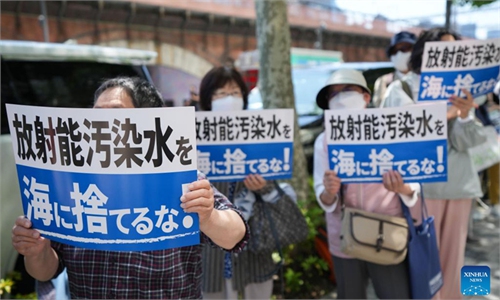

Editor's Note:The process of Japan's dumping of nuclear-contaminated wastewater into ocean has begun. Regardless of concerns from neighboring and worldwide countries over the spread of hazards, Japan has started sending seawater into an underwater tunnel that has been built to release Fukushima nuclear-contaminated wastewater into the sea. Against this backdrop, Marcos A. Orellana (Orellana), a UN special rapporteur on toxics and human rights, told Global Times (GT) reporter Li Aixin that Advanced Liquid Processing System (ALPS) method is insufficient, and the UN special rapporteurs have not received evidence regarding the application of the water treatment technology that would conclusively and compellingly dispel this concern.

This is the seventh piece of the series.

GT: The Japanese government has been claiming that the release of "treated" nuclear-contaminated water is safe. Still, we noticed that you mentioned the dumping would impose considerable risks to the full enjoyment of human rights of concerned populations. Can you elaborate on the view? How serious would the risks be?

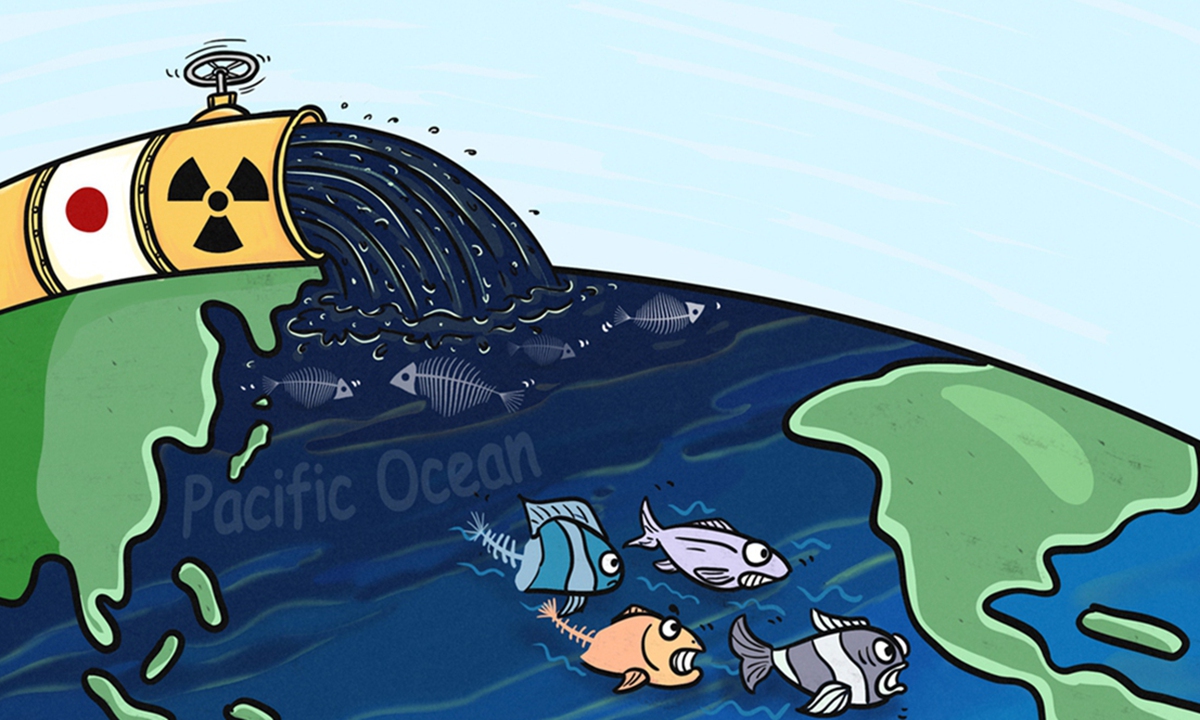

Orellana: Several UN Special Rapporteurs have sent the Japanese government a letter expressing our concern about the plans to discharge contaminated water into the Pacific Ocean. Japan has replied noting that it has treated water using ALPS technology. However, we are concerned the ALPS method is insufficient because it does not treat some radioactive elements such as carbon-14 and tritium. If discharged, this contaminated water moves up in the food chain, affecting plants and fish and ultimately can affect humans. The radiation is of low dose, but tritium's half-life is about 12.3 years. So, for more than 100 years, the low dose radiation may impact on people and environment in the Pacific.

GT: In 2021, you mentioned in a statement, UN experts have voiced their concerns to the Japanese government about the potential threats to human health and the environment resulting from the discharge of radioactive water to the Pacific Ocean. Now two years later, do you hold on to the same stance?

Orellana: UN Special Rapporteurs have sent the Japanese government a letter expressing concern about the discharge of contaminated water from Fukushima. Since Japan's original reply to that letter, the UN Special Rapporteurs have not received additional evidence regarding the application of the water treatment technology that would conclusively and compellingly dispel this concern. States should honor their duty to prevent exposure to hazardous substances.

GT: The Tokyo Electric Power Company started to send seawater from June 5 afternoon into an underwater tunnel that has been built to release Fukushima nuclear-contaminated water into the sea. What do you think is the major reason for Japan to stick to its discharge plan despite domestic and international concern?

Orellana: Japan has argued that there is not sufficient space to continue storing the water at the Fukushima facility. But while the specific facility may be running out of space, there are other ways to store water contaminated with radioactive elements next to the facility.

Japan has also argued that it is addressing the aftermath of Fukushima comprehensively. In order to support this narrative, the water of Fukushima needs to be dealt with. Otherwise, the contaminated water on site continues to remind the population about the risks of nuclear power and the Fukushima catastrophe.

Marcos A. Orellana Photo: his Twitter account

GT: Is there a more scientific and safe alternative to dumping nuclear-contaminated wastewater into the ocean?Orellana: International environmental organizations ban the dumping of radioactive waste to the oceans, including high-level and low-level radioactive wastes. That is because of the serious risks and harms posed by radioactive wastes to the marine environment and human health. Humanity cannot afford to aggravate the toxification of the planet.

GT: So far, we have not heard any opposition from the US on the official level. Do you take it as an encouragement for Japan?

Orellana: Japan has sought international support for its decision to discharge water contaminated with radioactive elements from Fukushima. For example, it has reached out to the G7 and to the International Atomic Energy Agency.

GT: What else can the UN and the international community do to mitigate the harm and risks of the release?

Orellana: States in the region whose rights could be directly infringed by the transboundary contamination with radioactive wastewater could seize the peaceful mechanisms for the settlement of disputes that have been established by international laws. The International Tribunal for the Law of the Sea, for example, has the power to indicate provisional measures to protect the marine environment and potentially could order Japan to suspend its decision to discharge contaminated wastewater to the Pacific. But to this date, neither China nor South Korea, has filed a complaint with that international tribunal.