Li Zhixing records a narration for a barrier-free movie in the dubbing room of the Guangming Cinema in Beijing on June . Photo: Lu Yameng/GT

In China's cinematic landscape, a groundbreaking revolution is quietly taking place at the Guangming Cinema, which embraced cutting-edge digital methods to immerse visually impaired people in the magic of storytelling through the medium of film.

"Welcome to the Guangming (Light) Cinema. Here we convey film through voice and perceive art through sound. Today you will experience the movie Ne Zha," a narrator explained to a group of young opinion leaders from 15 countries.

As they settled into their assigned movie theater seats, the 16 international youth opinion leaders from 15 countries were about to have a unique viewing experience at the Guangming Cinema in China's capital of Beijing. Here, they got to "watch" a movie while blindfolded, to learn what a movie-going experience is like for those living with visual impairment.

They sat in front of a screen, listening carefully to the sounds from the movie. Throughout the movie screening, along with the character voices, film score, and background action sound, those taking part in the sensory experiment also heard the voice of a narrator describing scenes, moves, and visual effects otherwise hard to enjoy without the sense of sight.

Actually, the movie these overseas young people were "watching" is a barrier-free movie - also named voice-descriptive movie, a product specially adapted for people living with visual impairment - created by a group of volunteers at the Guangming Cinema to allow visually impaired people to enjoy the equal right of walking into a cinema and enjoying a well-rounded movie-going experience like people with sights would have.

The Guangming Cinema Audio-descriptive Movie Making and Promotion Project, a public welfare project established by the Communication University of China (CUC) in Beijing in 2017, aims to create reproducible and transmittable audio-descriptive products to meet the growing spiritual and cultural needs of the visually impaired.

The movie Ne Zha, which deeply moved the audience of young international visitors, is just one of several hundred barrier-free movies that come with complete narration and are re-recorded by volunteers.

Data showed that there are 17.32 million people living with visual impairment in China, and the number of people with dyslexia may be even higher. To meet the cultural and spiritual needs of such a large population posed a great challenge for Chinese society and related government departments in the past.

In the plan for protection and development of disabled people during the 14th Five-Year Plan (2021-25) period, the Chinese government pointed out the necessity of supporting people living with disabilities and enhancing the quality of public services, such as rehabilitation, education, culture, and sports. The creation of a barrier-free environment in China has become an important aspect of promoting the modernization of the national governance system and governance capacity.

The Guangming Cinema Project is a vivid example of the country's efforts to build a barrier-free environment for the visually impaired. Since its establishment, the project has provided rich inclusive and culturally relevant products for a large number of visually impaired people.

As of May 2023, the Guangming Cinema has produced 520 barrier-free movies and two barrier-free television series, and has carried out public welfare screenings in 31 provinces, municipalities, autonomous regions, and the Macao Special Administrative Region, reaching over 2 million people across the country.

Overseas Gen Zers enjoy a barrier-free movie at the Guangming Cinema in Beijing on June 18, 2023. Photo: Courtesy of Tencent

Arduous but rewarding process

At the Guangming Cinema, a group of volunteers including professors, undergraduates, and postgraduate students, have devoted most of their leisure time participating in activities related to the film project, such as the re-recording of barrier-free movies, coordinating and promoting the screening of such movies, with the desire to help visually impaired people to experience and enjoy the world through cinema.

Xue Hanjie, a junior undergraduate student majoring in radio and television editing at the CUC Television School, told the Global Times that she joined the project in her freshman year and worked as a volunteer in the project's production group.

For Xue and other volunteers with the project, making barrier-free movies is not only about describing the stories in a movie, but also about helping the visually impaired to understand the meaning that the director wanted to convey to audiences. The opening shot, the landscape, the appearance and movements of a character, any and all aspects pertinent to the development of the plot are narrated, to help those who are visually impaired to gain a complete picture of what's happening in the movie.

Sometimes, when there are too many characters and different languages in a film, narrators dub the movie in Chinese and in different voices, so that the visually impaired can fully understand the plot only by listening.

In the dubbing room, volunteer Li Zhixing, a postgraduate student at the CUC, watches the scenes of a movie and actively adjusts his emotions and voice accordingly. Judging from the needs of the role, he sometimes plays the role of a young soldier, and then switches to the voice of an old man.

In order to control the voice performance of the actors and accurately convey emotions, a seemingly simple sentence has to be repeated and recorded four to five times over.

At the same time, outside the dubbing room, two volunteers at the tuning table align Li's dubbed dialogues and narrations with the appropriate scenes in the movie being worked on.

Cai Yu, a PhD student from Television School at the CUC, and also a volunteer with the project for about six years, explained that the making of a movie is usually time consuming and detail oriented. "In the beginning, we invite a volunteer to write the narration script. Teachers and other volunteers then review and proofread the script three times, polish the details, and then we start recording in the dubbing room, and go through editing, film encoding, and finally reviewing," Cai elaborated.

On average, narrating and dubbing a 90 to 120 minutes' film usually takes two to three months. A volunteer can usually only make one film over the course of one semester, Cai said.

The professionalism and responsibility of volunteer work left a deep impression on the overseas youth opinion leaders.

"Empathy and understanding were the thoughts that came to my mind when we were exposed to the project and the movie. It was a moving experience since I was able to put myself in blind people's shoes," Jose Carlos Feliciano, deputy director of the Center for China and Asia-Pacific Studies, University of the Pacific, Peru, told the Global Times after having a visually impaired movie-going experience.

Igor Alexander Bello Tasic, founder and CEO of Meta Ventures from Spain, said that when he wore the blindfold and "watched" the movie, he could feel that volunteers were not performing a technical job, but an artistic one.

They were not just trying to create a layer of information, but were narrating the story in a way similar to "Director's cut" - a human layer that connected that media with people who could experience it in its original form, Tasic said.

'Human reality' of volunteers

Due to work experience, Tasic knows some of the technologies related to visual reality and augmented reality, but at the Guangming Cinema, he said that what he felt was a sort of "human reality," a humanization of senses that he has never seen before.

The project has attracted more and more like-minded students, who want to help improve the quality of life of those living with visual impairment in the Chinese society. Cai said that each year, about 100 undergraduates and postgraduate freshmen join the project's volunteer team.

Rida Hameed, a journalist with Pakistan's K21 News, said that visiting the Guangming Cinema was the best moment of her life, giving her a sense of peace and satisfaction that there are people in this world who don't work for money but for the sake of humanity and kindness.

The Guangming Cinema now aims to produce 104 barrier-free films each year. "There are 52 weeks in a year, and we want to ensure that at least two barrier-free movies are provided for the visually impaired every week," Xue told the Global Times.

In the control room, the visitors saw printed movie narration scripts stacked into two 50-centimeter-high piles beside the tuning table. According to preliminary statistics, the number of words written by the volunteers in one year can be as many as 3 million.

"I was able to see the editing process for the voices, and realized that it really takes a lot of time and patience. The project has a long working hour process and requires great commitment (from the volunteers)," said Feliciano to the Global Times.

At the end of the year or during special occasions, the project team integrates the barrier-free movies and saves them in specially-made mobile hard disk drives and U disks, so that these movies can be played on computers even in the remotest villages in China. The team also stores movies in audio recorders with a memory card in it, allowing people with visual impairment to listen to the movies anytime and anywhere.

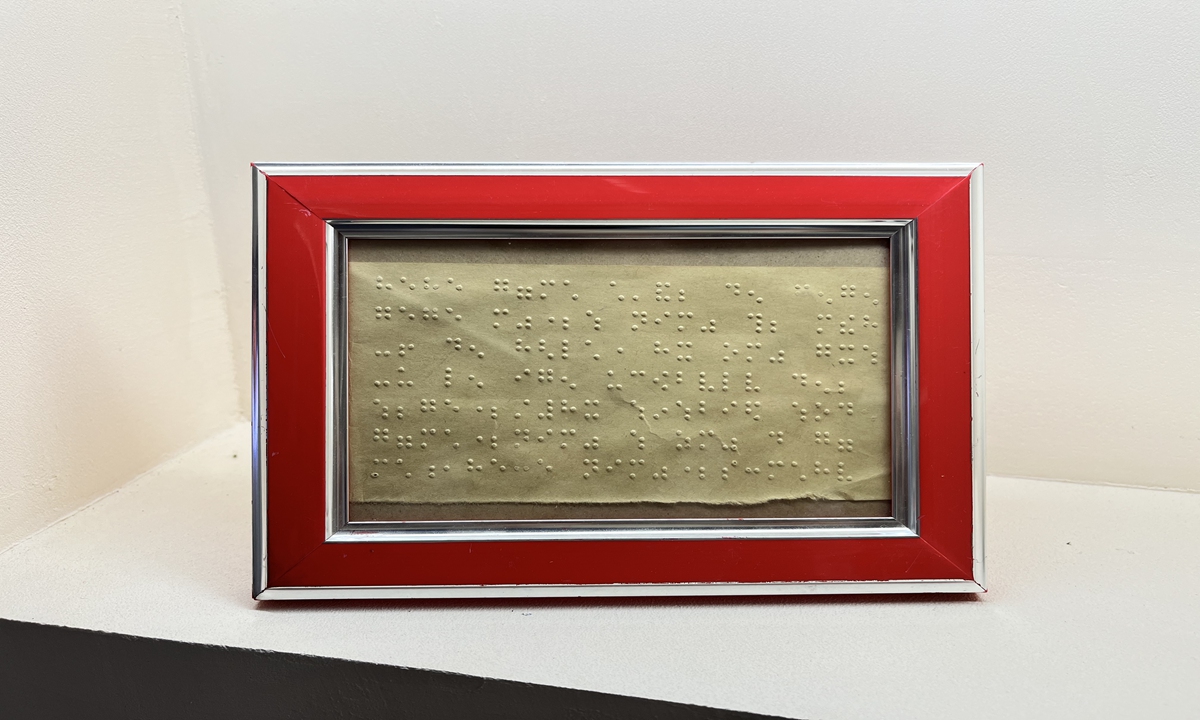

A piece of Braille text written by a little girl from the Beijing School for the Blind to the Guangming Cinema. Photo: Lu Yameng/GT

Pursuing for 'bright' future

In May 2022, the Marrakesh Treaty, which is the first and only human rights treaty that is copyrighted, officially came into effect in China.

The treaty allows authorized entities to produce print formats of cultural works geared toward those living with disabilities without authorization from copyright holders, from Braille books and audiobooks to films and TV shows. Experts noted that it is a practical move that China adopted to expand the country's human rights protection sphere for some 17 million print-disabled people, giving them equal access to culture and education.

Based on the Marrakesh Treaty, the Guangming Cinema has carried out many public warfare activities for people with visual impairment. Since April 2021, the project team has cooperated with the Beijing School for the Blind to screen barrier-free movies for children once a month.

In the Guangming Cinema, a special collection attracted the international visitors' attention and deeply moved them. It was a Braille text written by a little girl from the Beijing School for the Blind to the Guangming Cinema, displayed in a 6-inch red photo frame, on which it reads "Everyone is someone's light, and you are our light."

In order to allow the visually impaired to gain the full movie-viewing experience, the volunteers also chose to screen barrier-free movies in places such as the Chaoyang Theater in Beijing, a highly populated residential area with convenient transportation facilities for visually-impaired people.

"We insist on providing barrier-free movies in theaters and cinemas, because we want to help achieve equal rights for those who are visually-impaired. They deserve an equal right to walk into a cinema and enjoy a movie," said Xue.

Additionally, volunteers from the Guangming Cinema went to remote places in China to carry out public welfare screenings, so that visually impaired people in those areas and people in ethnic minority areas could also enjoy the cultural experience brought by movies. The movies and television series made for people living with disabilities by the project volunteers were also sent out to 2,244 special education schools across China.

As of 2021, there were 2,288 special education schools in China, increased from 1,933 in 2013, according to the Report on the Cause for Persons with Disabilities in China (2023) issued in May, 2023. This means that about 98 percent of special education schools in China have benefited from the project, where students in said schools can enjoy barrier-free movies made.

Feliciano told the Global Times that in Guangming Cinema, he was impressed by how digitization was used to empower philanthropy and social projects in China. "It's very interesting to see how Chinese innovative solutions can be an inspiration to other countries," he said.

He also said that he would share the digital example with his students and write articles about what he had learned on his trip in China, to let more people know about China's practices in the digital sphere.

This is really a noble cause and other countries in the world must learn from how China is taking good care of its people, not only at present but are also trying to make the future better as well, Hameed said.