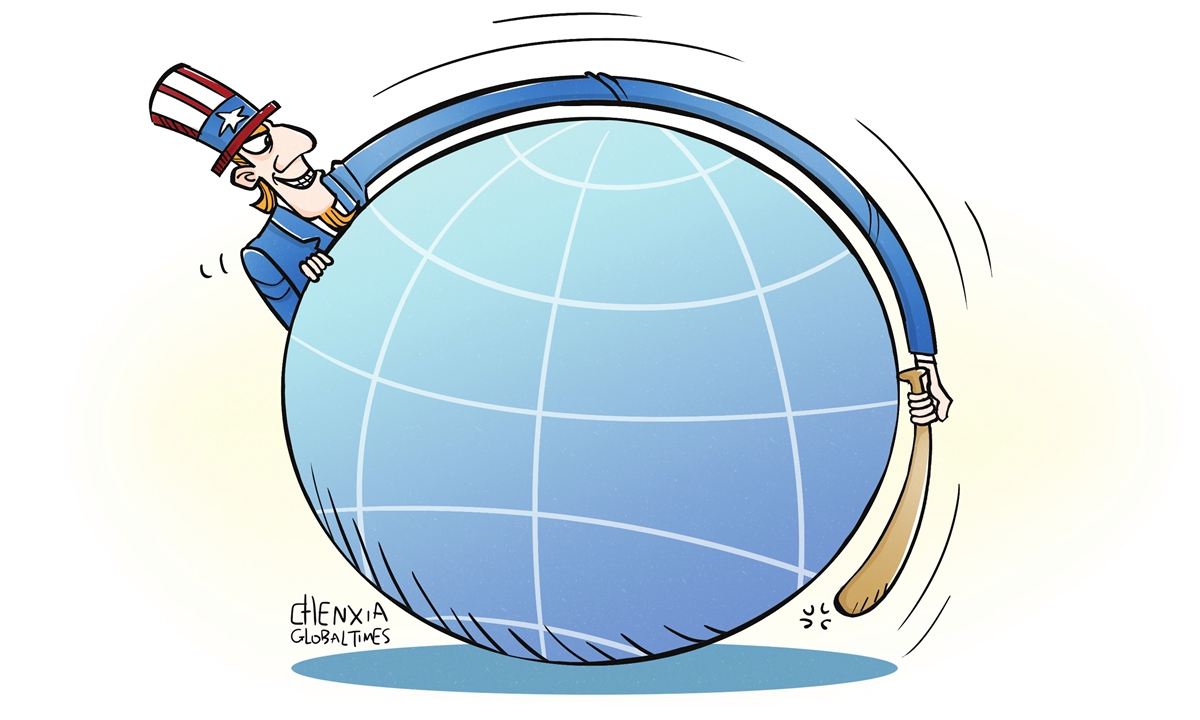

Illustration: Chen Xia/GT

On March 16, the US Congress introduced the Transnational Repression Policy Act, stating to "hold foreign governments accountable when they stalk, intimidate, or assault people across borders," which "would help elevate countering transnational repression as a key foreign policy priority of the US." Although the 32-page bill did not explicitly mention China, several members of Congress directly addressed China in their statements. The US has long suppressed dissent through secret surveillance, illegal wiretapping, global manhunts and behind-the-scenes deals. The "transnational repression" is an allegation that best matches the US' own practices.The US, the pioneer of "long-arm jurisdiction," is now attempting to capitalize on this concept that it devised and to use it against China. For example, the infamous PRISM program has revealed that the US is the world's biggest safe haven for hackers perpetrating indiscriminate and illegal cyber espionage and surveillance throughout the world. Confronted with unjust accusations from the US regarding overseas Chinese individuals, one can't help but wonder if the US government has forgotten about the PRISM program.

Every instance of "long-arm jurisdiction" the US employs is adeptly packaged. On April 17, the FBI arrested two Chinese-American residents in New York City under suspicion of "operating illegal overseas police station of the Chinese government." The US government alleged that they were "monitoring and intimidating dissidents and those critical of its government through China's repressive security apparatus." Through the smear of "transnational repression" and the introduction of a related bill, the US claims that this is "part of a broader strategy to advance democratic principles and respect for human rights, domestically and internationally."

However, in reality, These moves are laying the groundwork for their potential abuse of "long-arm jurisdiction" against China in the future. Just as they attacked China over the alleged genocide in the Xinjiang region, nobody can ensure the authenticity, objectivity, scientific basis and impartiality of the fraudulent Xinjiang-related "databases" and the so-called witness testimonies. More importantly, who granted the US the authority to meddle in the affairs of other sovereign nations and even conduct legal trials regarding such affairs? In fact, the US understands the answers to these questions better than anyone else, because those who wrong you often know better than you how you've been wronged.

The US, which recklessly employs "long-arm jurisdiction" everywhere, acts as a social menace without any sense of "boundaries," inflicting various hardships on the global community. In reality, "long-arm jurisdiction" itself isn't inherently derogatory. International law possesses its inherent limitations, coupled with the rapid transformations occurring in the global economy and societal structures, making it challenging for international regulations to keep pace with the times. As a result, often there's a need to fill the gaps in international rules with existing domestic laws that are objective, impartial and grounded in science. This should represent the rational intention of sovereign nations extending the application of their domestic laws beyond their borders. Furthermore, during the era of globalization, large economies will inevitably "go global," and the protection of the legitimate rights of their nation and its citizens demands some form of extended criminal jurisdiction over foreign affairs.

China is no exception to this principle. Confronted with an increasing demand for safeguarding overseas interests, we should contemplate how to establish our own "long-arm jurisdiction" system. However, this approach differs fundamentally from the US model of "long-arm jurisdiction."

First, China's expansion of extraterritorial jurisdiction is not boundless; it still adheres to the "boundaries" between nations and seeks equilibrium between domestic laws and international regulations. At the very least, there exists a basic and unequivocal criterion: respect for the sovereignty of each nation. Elaborating on this, there's the noninterference principle that China has consistently upheld.

Second, China doesn't forcefully impose its will as a hegemon. Instead, it positions itself as an equal partner, assuming the role of an international peace guarantor. We either provide our nation's legal governance experiences as reference points to the global community - for instance, the International Organization for Mediation established in Hong Kong in February, the world's first intergovernmental legal organization dedicated to resolving international disputes through mediation - or during the process of establishing a new international order, we're willing to patiently heed the opinions of other nations, respect their national contexts and citizens' choices, and employ diplomatic channels to amicably resolve conflicts and seek mutually beneficial solutions, thereby achieving the utmost "win-win" scenario.

Of course, a fair and just international order with a clear sense of "boundaries" can't solely rely on the proactive endeavors of predominantly well-intentioned nations. It's advised that the US don its own shoes, walk its own path, exercise more "boundaries" in international interactions, and desist from stretching its arm too long.

The author is an associate research fellow at the Institute of American Studies, China Institutes of Contemporary International Relations. opinion@globaltimes.com.cn