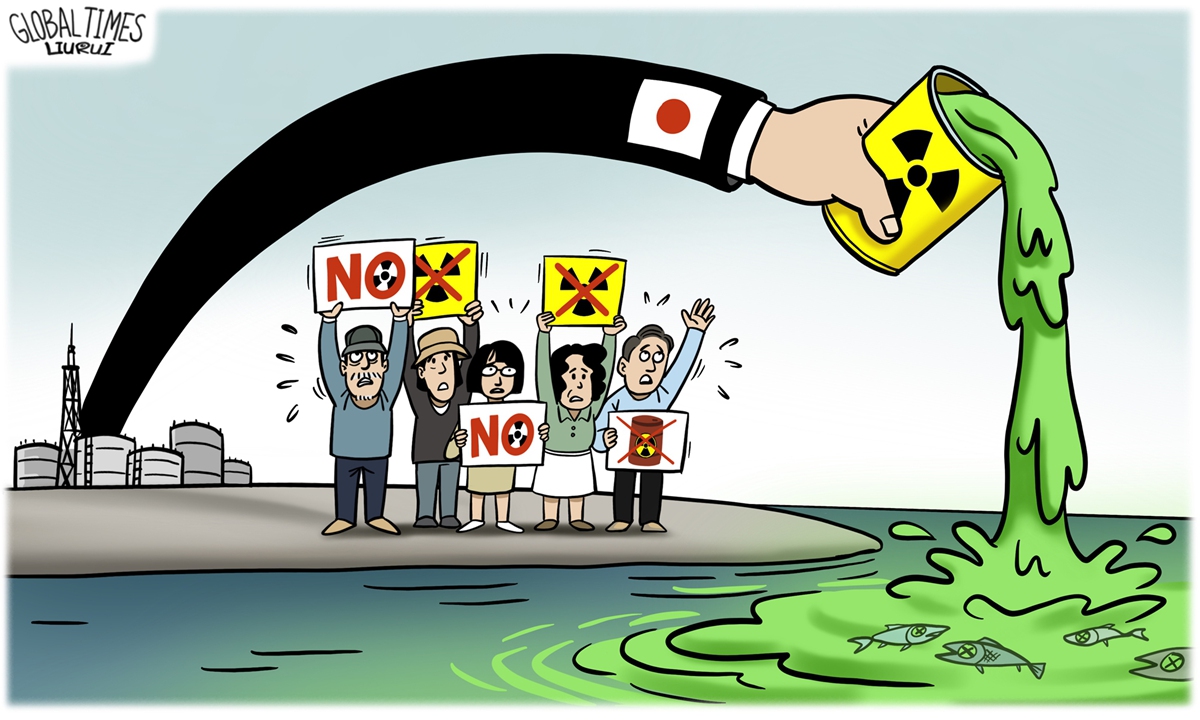

Illustration: Liu Rui/GT

The second round of dumping nuclear-contaminated wastewater from the wrecked Fukushima Daiichi nuclear power plant into the sea began on Thursday. According to Japanese media reports, this round of dumping is expected to last for 17 days, and a total of approximately 31,200 tons of nuclear-contaminated water will be discharged before the end of March next year. Japan defends its decision to continue dumping nuclear-contaminated water by unilaterally claiming that "no abnormal levels of tritium and other radioactive substances have been detected in seawater or fish samples collected from around the nuclear power plant since the first round of the discharge running from August 24 to September 11."What Japan refers to as "no abnormal levels" only means that the nuclear-contaminated water meets the standards set by the International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA) after treatment. Some Western politicians and scientists argue that the "treated water" can be drunk. However, it's important to note that none of them have actually consumed the water themselves, and it is unlikely they ever will. Consequently, Japan is using the IAEA's "license" to promote the discharge of nuclear-contaminated water in the international community and attack countries and individuals who oppose the dumping as "anti-science." South Korean President Yoon Suk-yeol has gone even further, considering the opposition party that opposes the discharge of nuclear-contaminated water as "anti-state forces."

Japan's claim that the dumped nuclear-contaminated water is "safe treated water" is only intended to confuse the public. In reality, even "treated water" does not necessarily mean it is clean water, and whether it is "clean" or not can only be determined by testing for radioactive substances. However, current technology may not be capable of detecting all harmful substances in water contaminated by nuclear radiation, and the technology to purify such water into truly clean water is limited. Even water that appears to meet the so-called "scientific standards" may be considered unqualified when tested in nature which has a complex biological chain.

If the "treated water" is truly safe, why wouldn't leaders of the US, Japan and South Korea, who support the discharge of nuclear-contaminated water, publicly consume it during their meetings?

Coincidentally, a report from a mainstream South Korean media outlet on September 28 wrote that even if the sewage treatment plant meets the standards and the discharged water is diluted, it can still have an impact on the ecosystem. Although it is said to have been treated, the treated water still contains a complex mixture of pollutants, nutrients and pathogens, which may cause hidden environmental impacts. It is worth noting that this report cited a research paper published by an international research team from Spain, Germany, Brazil and other countries in Volume 347 of the Journal of Environmental Management, which investigates the environmental impact of treated water discharged from sewage treatment plants.

The report noted that meeting scientific standards does not necessarily mean meeting ecological standards. Even if sewage appears to have been treated and meets the so-called standards, when it is discharged into the natural environment, long-term observation and comparison will reveal that it could cause considerable destructive effects on the entire biological chain and the environment.

The approach taken by Western governments such as the US and South Korea to Japan's dumping of nuclear-contaminated water is based on political judgment under the guise of science, without fully considering its long-term negative impacts on the health of all human beings and the safety of marine ecosystems.

The Japanese government should take the legitimate concerns of the international community seriously and immediately stop dumping nuclear-contaminated water. It should conduct more transparent and long-term examinations to determine whether the so-called "treated water" will have destructive effects on the environment and the biological chain, rather than simply brushing it off.

The author is the director and professor of the Center for Korean Peninsula Studies at the Shanghai University of International Business and Economics. opinion@globaltimes.com.cn