The 10th Beijing Xiangshan Forum – from balance of powers to balance of interests

Illustration: Chen Xia/Global Times

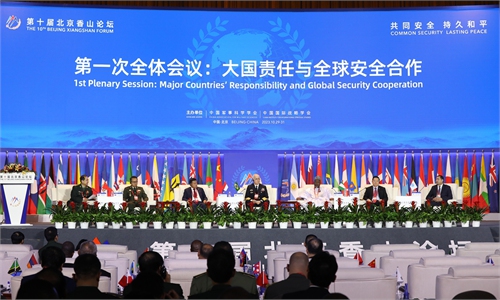

The 10th Beijing Xiangshan Forum, which took place in Beijing from October 29 to 31, was in no way yet another routine expert event on international security matters. The forum summoned about 1,800 international security experts from all over the world, including many men and women with big stars on their shoulders. It involved both official delegations from more than 90 countries and international organizations led by high-ranking governmental representatives up to the level of the Ministers of Defense and Heads of General Staff and some of the brightest independent scholars working on various dimensions of the vast international security agenda.The event was a graphic illustration of the breadth of China's engagement in international security cooperation. According to General Zhang Youxia, vice chairman of the Chinese Central Military Commission, who delivered the keynote speech at the opening of the forum, today China participates in more than 600 international conventions.

The forum remains one of the very few venues, where you can still see a US general comparing notes with his Russian counterpart, and a security expert from Saudi Arabia chatting friendly with his colleague from the Islamic Republic of Iran.

However, it was not only the scale or the inclusiveness that made the forum such an outstanding event, but the thematic priorities and the overall atmosphere. The majority of security-focused international forums, especially those that have a strong army brass presence among participants, tend to concentrate most of their attention on regional or global balances of power. At many forums capabilities of nation-states are presented as far more important than political intentions. As a rule, deliberations are based on the assumption that material resources outweigh values and moral considerations and at the end of the day, hard power always prevails over soft power.

The world of realpolitik is a cruel and merciless place, especially for small and medium-sized nations. If big players can afford true sovereignty, and almost unconstrained foreign policy independence, international actors of smaller size have no other choice but to bandwagon to their stronger partners and allies, even if such bandwagoning turns out to be detrimental to national interests and aspirations of the former. As a famous US film director, Stanley Kubrick, aptly put it, in the world of power balancing "The great nations have always acted like gangsters, and the small nations like prostitutes."

One could expect a highly professional group summoned in the Beijing International Convention Center to concentrate mostly on the nuts and bolts of the shifting balances of power: missile warheads counting, comparing technical characteristics of modern tanks and armored personnel vehicles, exchanging views on the lessons learned from recent military conflicts and speculating about the likely role of AI in the future warfare. Though all these and many similar topics were indeed preset on the agenda of the forum, participants spoke more about security interests than about sheer power and military capabilities. If I were to summarize the forum's discussions in one phrase, I would say that the big question of the event was about how to find a way to move from the balance of power to the balance of interests as the foundation for the new global security order.

Critics of this approach would probably argue that hard power is solid, while interests might be fickle. Raw power is easier to measure and its dynamics are easier to monitor. However, there are many examples in history, including recent history, of nation-states grossly underestimating the power of their adversaries and overestimating their own capabilities.

Then again, if the name of the game in world politics is constantly shifting the balance of powers, the quest for changing this balance in your favor might become irresistible thus leading to fierce competition in arms or economic might. Moreover, if you feel that the balance is indeed changing in your favor, you might be tempted to capitalize on the perceived change by provoking your adversary and expecting him to yield. Many wars started precisely because the adversary did not agree with the calculus on the other side, and was reluctant to yield and instead preferred to escalate.

Of course, balance of interests is still a novel concept, which is waiting to be properly conceptualized and operationalized. One could not expect the 10th Beijing Xiangshan Forum to provide detailed answers to many questions arising from this concept. No two nations on this planet have identical interests, these interests may coincide, overlap or collide with each other. So, how can a line be drawn between the "legitimate" and "illegitimate" interests of a nation-state? What is the difference between truly national interests and powerful group interests that try to speak on behalf of the whole nation, but do not really represent it? How far should political leaders go to try to accommodate the interests of their opponents in order to reach a sustainable compromise?

The picture becomes even more complicated once we approach the balance of interests not on the bilateral, but on the multilateral level. If the changing balance of power in the world implies a shift from the unipolar to the multipolar system, trying to fix the balance of interests requires a move from predominantly unilateral foreign policy to true multilateralism. While multipolarity is something that humankind has experienced more than once in its long history, true multilateralism remains to a large extent uncharted waters to most nation-states. This is especially true for some great powers, which have developed a nasty habit of trying to impose their will on weaker players instead of seeking a mutually acceptable balance of interests.

Still, the shift from the balance of powers to a balance of interests is critically important, if humankind wants to survive through the 21st century. The future does not belong to "gangsters" or "prostitutes," it belongs to responsible players ready to respect each other and to fine-tune a delicate balance of interests, not a crude balance of power. It is also important that this idea is promoted by China - a nation that has all the resources needed to successfully play the old balance of power game. Only by fundamentally changing the core paradigms of our thinking, can we achieve common security and lasting peace - the ultimate goal reflected in the theme of the 10th Beijing Xiangshan Forum.

The author is the academic director of the Russian International Affairs Council. opinion@globaltimes.com.cn