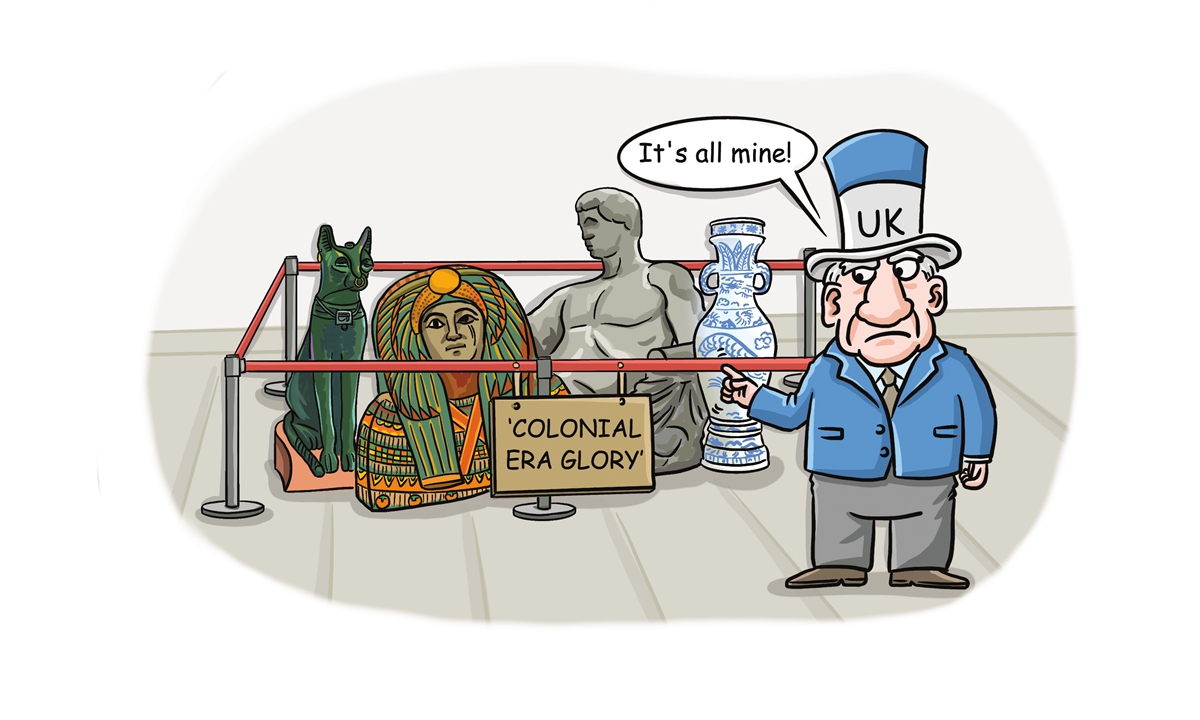

Illustration: Xia Qing/GT

It is possible to present an argument in favor of a museum's relics being retained and displayed and not returning them to their land of origin. However, it doesn't hold up when you hear the other side. One argument in favor of repatriation that overwhelmingly tips the rhetorical balance is quite simple: The objects do not belong to them.

For the past 60 years, the British Museum has relied upon a very convenient law that prohibits the return of artifacts to their home countries, regardless of how they were plundered or misappropriated. This is why the museum's trustees refuse to hand back Chinese artifacts or those from other nations, such as Greece.

They say such objects are legally theirs and would be safer if kept in London (an assertion undermined when it was recently alleged an employee had taken almost 2,000 objects from the museum's collection - including gold objects and semi-precious stones - and sold them on eBay).

It gets worse. Britain's intransigence and arrogant attachment to the bygone age of its Empire - when up to a quarter of the world's land surface was ruled from Whitehall - created a preposterous diplomatic incident between the UK and Greece.

When the British Empire conquered, colonized and subjugated about 458 million people at its height, it was considered perfectly acceptable to steal the antiquities of other cultures to cart home as trophies. Though Greece was never part of the British Empire, it was subjugated by the Ottomans, and it was from them that Britain's ambassador to Greece in 1801 says he was given permission to take antiquities from the Parthenon. Nobody asked the Greeks what they wanted. Even in Georgian England, the acquisition was controversial, with some accusing the diplomat of cultural vandalism. However, the country's elite - in the form of parliament - closed ranks around him and declared his actions legitimate.

It is well known that Greece has for generations insisted the stone carvings taken from the Acropolis in the early 19th century belong in Athens. In Britain, where they have remained since 1803, they are called the Elgin Marbles, named after the British lord who swiped them. Greeks, on the other hand, call them the Parthenon Marbles, after the Classical archaeological site where they had remained safely for more than two millennia before the British tore them down.

Greek Prime Minister Kyriakos Mitsotakis arrived in the UK over the weekend ahead of a planned meeting with his UK counterpart Rishi Sunak. Topics such as the war in Ukraine, the Middle East crisis and climate change were said to be on the agenda. It was widely anticipated that the Parthenon Marbles would also be raised.

On Sunday, Mitsotakis was interviewed on BBC television and repeated his country's long-held position that the Marbles in the British Museum should be reunited with the other half of the frieze, currently in Athens' Acropolis Museum. He said that leaving half in the UK would be "like cutting the Mona Lisa in half." For Greece, the Marbles are about much more than ownership, they are a direct link to their illustrious forebears in Fifth-century Athens and a symbol of immense national pride.

Just how sensitive Britain is about its historical piracy was then revealed by Sunak's wildly disproportionate reaction, "irritated" by the Greek PM's comments. He canceled the meeting the two had long planned. Hours before the 45-minute meeting scheduled for Tuesday lunchtime, the British called it off. Mitsotakis flew home without discussing the Marbles, or anything else on the agenda. He was probably as baffled as most people about why Sunak took such umbrage.

Sadly, Britain has a track record of holding on to other countries' heritage objects, as China knows well. In August, China joined a growing list of nations demanding that the British Museum repatriate artifacts from its collection, in Beijing's case about 23,000 Chinese national treasures that were improperly acquired. The request was met with the same response given to the Greeks - that the British Museum Act of 1963 forbids the return of any object unless it is duplicated, damaged and no longer of public interest. The law, however, was designed to keep in Britain what patently does not belong to Britain, and perhaps a reasonable government - once its prime minister has calmed down - might consider new laws that would allow justice to be done. Even so, this is not about the law.

Both the British Museum and the UK government claim that the artifacts were legitimately acquired and are legally owned. They fail to see that the law is not the overriding issue here. It is a moral issue. It's about doing the right thing.

Britain still clings to its colonial past like a child to a comfort blanket. Many see the UK's colonial legacy not as one of exploitation but as a reminder of a past when Britain really could be called "Great." This provides a warped justification for institutions here to hoard cultural objects that don't belong to them. They also miss the point that justice, rather than legality, is the issue here - restorative justice, perhaps with an acknowledgement of wrongdoing. It would be a way of apologizing for the wrongs of the Empire; failure to do so perpetuates the outmoded ideas that have enabled places like the British Museum to build such a fabulous collection of eight million objects - many of which come from ancient civilizations and don't belong there.

The author is a journalist and lecturer living in Britain. opinion@globaltimes.com.cn