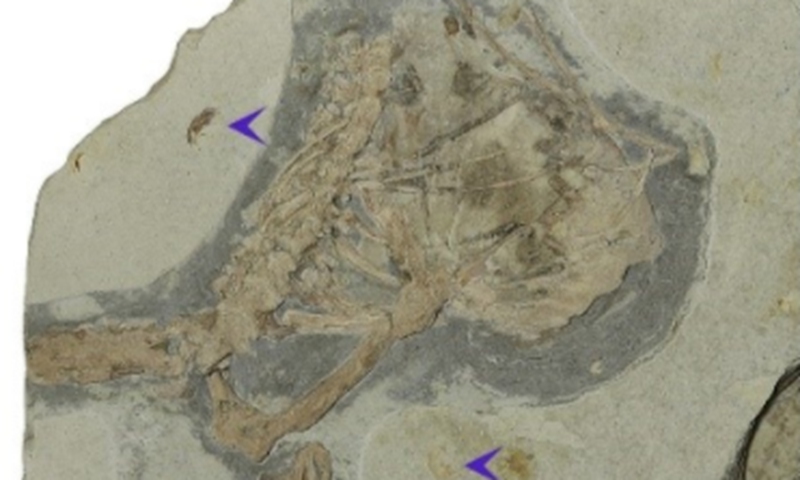

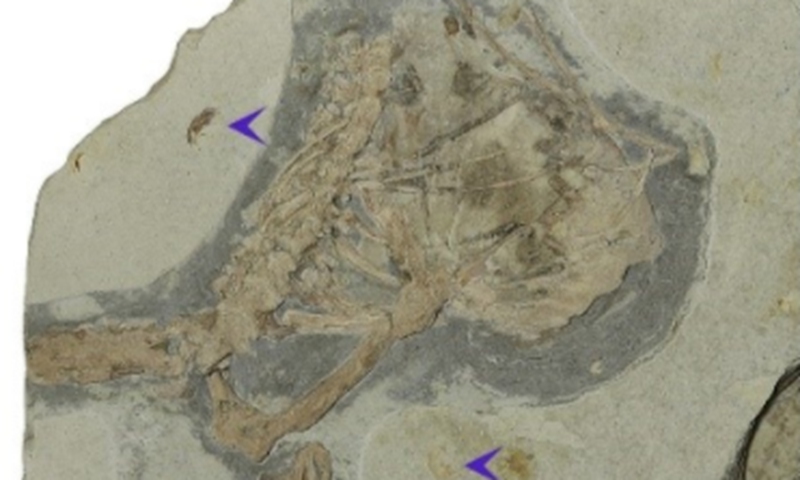

Part of the fossil of Cratonopterus Huabei Photo: Courtesy of Institute of Vertebrate Paleontology and Paleoanthropology

Is the hollow bone structure of pterosaurs an adaptation to reduce weight for flight? Is the relatively thick bone wall a unique feature of the Junggar pterosaur group?

A new species of pterosaur recently found by Chinese scientists in North China's Hebei Province challenged many traditional understandings about pterosaurs in the field of paleontology and provided revolutionary insights into the evolution of their bone wall.

The new species was named

Cratonopterus huabei, according to latest findings by a research team with the Institute of Vertebrate Paleontology and Paleoanthropology, Chinese Academy of Sciences. The Chinese team conducted in-depth research on pterosaur fossil materials collected from the approximately 130 million-year-old strata of the Jehol Biota in China.

"Craton," from the Greek "Kratos", means strong, solid, referring to the Earth's crust layer where the specimen was found and "pteron," in Greek, means "wing," often used for pterosaurs.

The new research paper on

Cratonopterus huabei was recently published in Heliyon, under the internationally renowned academic journal Cell.

The Early Cretaceous terrestrial Jehol Biota in Northeast China has been famous globally since the early 1990s for producing feathered dinosaurs and many other exceptionally preserved vertebrate fossils. This biota was divided into three evolving stages, as represented by fossil assemblages from the Huajiying (early), Yixian (middle) and Jiufotang (late) formations, according to the institute.

Cratonopterus huabei is the second fossilized pterosaur discover in the Huajiying Formation which represents the early stage of the Early Cretaceous Jehol Biota. Though incomplete, the partial skeleton includes vertebrae (cervical and dorsal), the sternum, the right scapulocoracoid and most elements of the right wing, Jiang Shunxing, a researcher with the team, told the China News Service on Sunday.

The only known pterosaur specimen was incomplete and assigned to the Ornithocheiroidea while

Cratonopterus huabei is assigned to the Ctenochasmatidae.

Cratonopterus huabei is a medium-sized archaeopterodactyloid with a wingspan of about 1.8 meters. It can be distinguished from all other members of the clade by the following autapomorphies: a large pneumatic foramen present on the ventral surface of the proximal end of the first wing phalanx, and coracoid lacking an expansion at its contact with the scapula, according to Jiang.

For a long time, pterosaurs have been believed to have a thin, hollow bone structure similar to birds. This type of bone structure is considered an adaptation for flight and is often explained as a means to reduce their weight during flight. Among pterosaur groups, the Junggar pterosaurs are considered a type with particularly thick bone walls, which is one of their distinguishing features. Some researchers have proposed that the thickening of the bone walls in Junggar pterosaurs is an adaptive characteristic for frequent take-offs.

Not belonging to the Junggar pterosaurs, the

Cratonopterus huabei also features a thick bone wall structure, which defied the conventional understanding of the pterosaurs' bone wall structure and offered a revolutionary revelation to the evolution of their bone wall.

The research team found that thick bone walls are not unique for the Junggar pterosaurs as previously thought, and the relatively thick bone walls are regarded as a primitive feature of pterosaurs, Jiang noted.

It was also discovered that not all Junggar pterosaurs have thick bone walls. For example, the bone walls of the humerus and radius are relatively thin. This phenomenon is also seen in living flying vertebrates such as bats.

Therefore, the relative thinning of the bone walls of the humerus and radius in Junggar pterosaurs is likely an adaptation similar to that of bats for flight. It increases their skeletal resistance to twisting during flapping flight, rather than merely reducing their weight, said Jiang.

The team's conclusion provides a completely new interpretation to the long-held belief that pterosaurs' thinning bone walls were solely for the purpose of reducing weight.