OPINION / GLOBAL MINDS

The end result of Russia-Ukraine conflict to be a frozen conflict devoid of a genuine peace agreement: John Mearsheimer

Smoke rises above buildings in the course of Russia-Ukraine conflict in Donetsk, Ukraine on February 19, 2024. Photo: IC

Editor's Note:February 24 marks the anniversary of the Russia-Ukraine conflict, which has been ongoing for two years with no end in sight. Why can't the conflict be resolved? As it continues, has the West's mentality of "defeating Russia" evolved? How does the conflict impact global geopolitical patterns? As the two-year anniversary approaches, the Global Times (GT) collected views within the US and Europe.

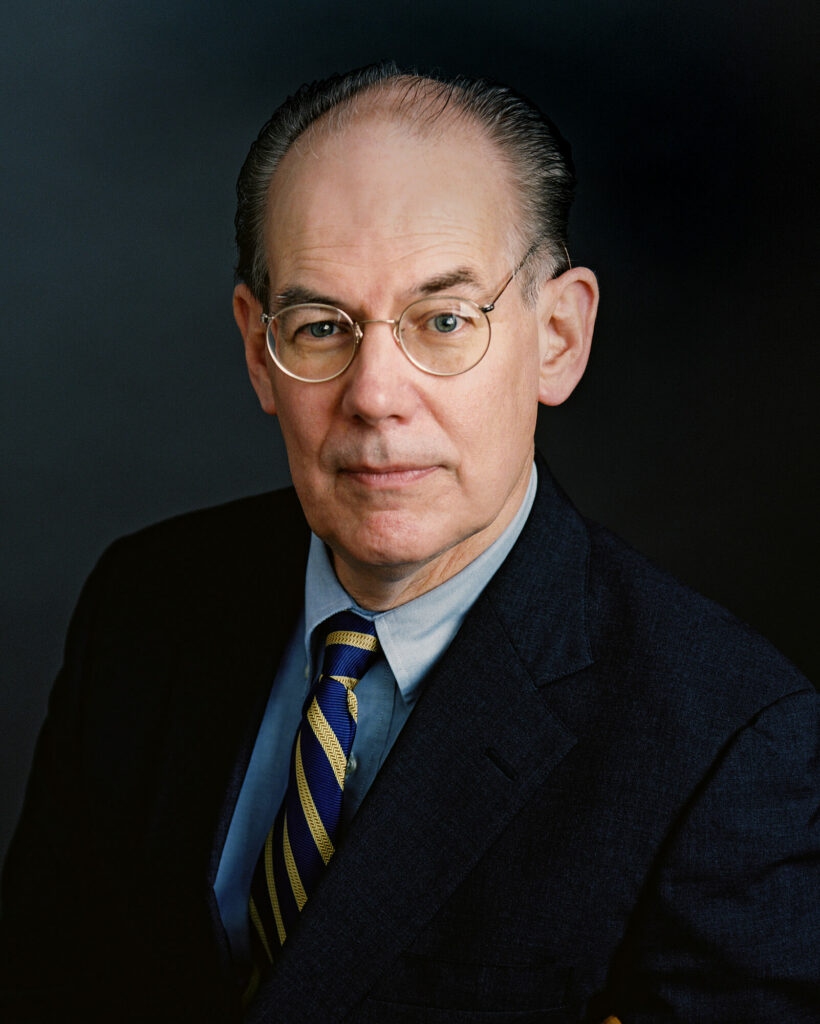

In the third interview of the series, John Mearsheimer (Mearsheimer), the R. Wendell Harrison Distinguished Service Professor in the Political Science Department at the University of Chicago, justified his long-held belief that the West is to blame for the conflict and US policy has failed.

GT: In a previous interview, you said the Ukraine conflict will be a long-term danger. Since the conflict is about to enter its third year, how long will it last? Under what circumstances will it end?

Mearsheimer: I think that the actual fighting will not last beyond 2025. The Russians will capture more territory than they now control, and there will be a cease-fire. The end result will be a frozen conflict, but you will not have a genuine peace agreement, and therefore, there will always be the danger that the frozen conflict will, once again, become a hot conflict.

The West, mainly the US, won't accept a final peace agreement where Russia captures a significant portion of Ukrainian territory. So even though you have a frozen conflict, the West and the Ukrainians will go to great lengths to subtly undermine Russia's position in the areas of Ukraine that it conquers.

At the same time, the Russians will go to great lengths to make sure that the Ukrainian rump state is a weak and dysfunctional political and economic entity. You will have this conflict that won't be a hot war, but will be a security competition between Russia on one side and Ukraine and the West on the other for as far as the eye can see. This is a very depressing situation, because there is really no end in sight to the conflict between the two sides. An acute and deep hostility will exist for a long time. I don't think that Russia will have good relations with the West or Ukraine at any point in the foreseeable future.

GT: You famously warned in 2014 that NATO was provoking Russia in Ukraine on the state of the war and the troubles ahead. Why such voices like yours were neglected?

Mearsheimer: When NATO decided to expand in the 1990s, there was a big battle inside the US. Opponents of NATO expansion who were basically realists said that if you expand NATO eastward, you're going to antagonize Russia and end up at some point with a serious conflict. They were opposed by an influential group of foreign policy liberals who believed that the US was a benign hegemon, and that the US could move NATO eastward toward Russia, and it would not lead to trouble. In the 1990s, Russia was very weak and could not do anything to stop NATO expansion.

So, the advocates of NATO expansion won the debate. The first major expansion occurred in 1999, and then the second in 2004. Very importantly, in April 2008, NATO, with prodding from the US, said that Ukraine will be brought into the alliance. The Russians made it unequivocally clear at the time that Ukraine in NATO represents an existential threat to Moscow and they would not allow it to happen.

Nevertheless, the US and its European allies continued to push eastward and continued to try to bring Ukraine into NATO. In February 2014, a major crisis broke out. This is when I wrote my famous article in Foreign Affairs saying that the West was largely responsible for the crisis. I said the principal cause of the crisis was NATO expansion, and more generally, the West's efforts to make Ukraine a Western bulwark on Russia's borders. I argued at the time that this was remarkably foolish, because the Russians clearly viewed it as an existential threat. And if we continued to push to bring Ukraine into NATO, it would lead to even bigger trouble.

Anyway, after the crisis broke out in February 2014, the US and its allies doubled down and continued pushing to bring Ukraine into NATO. Every time the Russians tried to work out a negotiated agreement to avoid a war, the Americans and their allies refused to negotiate with the Russians. They told the Russians that they had to accept that Ukraine would become part of NATO. But the Russians refused to accept this outcome. And in February 2022, eight years after the conflict first broke out in February 2014, the Russians invaded Ukraine, because they were determined not to let Ukraine become part of NATO.

GT: You published a new book, co-authored with Sebastian Rosato, How States Think: The Rationality of Foreign Policy, in which you argue that NATO expansion was rational. You also believe that Putin's hard pushback against it was also rational. How should we understand these decisions, which ended up leading to war?

Mearsheimer: In our book, one of the things that we had to do was answer the question: What does it mean for a state to be rational? Our argument is that a state is rational if it has a credible theory about international politics that underpins the relevant policy that the state is pursuing. We also argue that because foreign policy decisions are collective decisions, and individuals often have different views on what is the proper policy, it is important that the decision-making process be done in a deliberative way so that people who are involved in the decision-making process have an opportunity to express their views and to question each other.

As I said before regarding NATO expansion, there were two groups that argued about whether it made good strategic sense. One group was comprised of realists who opposed NATO expansion. They based their view on basic realist theory. They had a realpolitik view of international relations. That is certainly a credible theory. Therefore, opposing NATO expansion was rational.

The proponents of expansion had a view that was based on the three big liberal theories of international politics - democratic peace theory, economic independence theory, and liberal institutionalism. These are all credible theories and widely accepted in the international relations literature; thus the policymakers who pushed NATO expansion were also acting rationally.

Our argument is that the two contending sides in the debate as to whether to expand NATO based their views on credible theories. Therefore, even though the side that I disagreed with won, I thought that it was pushing forward a rational policy. This discussion shows that there's a difference between being wrong and being rational. I thought the proponents of NATO expansion were wrong, but I believe they were rational.

With regard to Vladimir Putin, this is a straightforward case of a country that felt that it was facing an existential threat from NATO expansion. It decided that to prevent that from happening, it would launch a war into Ukraine. This is called a preventive war. A preventive war, whether one likes it or not, is rational. Thus, I think that Putin was behaving in a rational manner when he invaded Ukraine. One can make a strong case that it makes good sense for a leader, faced with an existential threat, to launch a preventive war. One could argue that the Russian invasion of Ukraine was a mistake or that it violated international law. You can make such arguments, but whether it's wrong or whether it's rational are two different things. I think it was rational because it fit very neatly with preventive war theory, which is a credible theory of international politics.

John Mearsheimer Photo: Courtesy of Mearsheimer

GT: Putin's latest interview with Tucker Carlson reveals how he envisions negotiations and peace. How much will the Western audience listen to him? How will the interview influence Western public opinion on the war?

Mearsheimer: It's very clear that Tucker Carlson's interview with Putin will have virtually no influence in the West. What's really amazing is the extent to which Western elites across the board had nothing but bad things to say about the interview and Putin himself. If you look at the Western response, there was no interest in responding in a positive way to anything Putin said. I think this interview will have zero effect on how the Ukraine war plays out.

GT: Ever since the war started, you have held the belief that the West is to blame and US policy is failed. Some think that you get Russia wrong. How would you refute such criticism?

Mearsheimer: The conventional wisdom in the West is that Putin started the war because he's basically an imperialist or an expansionist. Specifically, he's said to be interested in creating a greater Russia, which means he is determined to conquer all of Ukraine. And then he's going to conquer other countries in Eastern Europe and create a new Russian Empire.

My argument is that this view is wrong; what Putin was doing when he attacked Ukraine was launching a preventive war. He did not have imperial ambitions. He was not committed to creating a greater Russia. His decision had everything to do with the fact that he viewed NATO expansion into Ukraine as an existential threat to Russia and he was determined to prevent that from happening.

So, I have a view that is directly at odds with the conventional wisdom in the West. You asked me, how would I show that I'm right and the conventional wisdom is wrong? The answer is simple. There is zero evidence to support the conventional wisdom. There is no evidence that Putin wanted to create a greater Russia. There is no evidence that he wanted to conquer all of Ukraine. And there is certainly no evidence he wanted to conquer other countries besides Ukraine.

On the other hand, there is an abundance of evidence that shows he was motivated by NATO expansion into Ukraine, or more generally, he was motivated by the West's efforts to make Ukraine a Western bulwark on Russia's border. He said on numerous occasions that this is unacceptable. I think all the available evidence shows that my position is correct, and the conventional wisdom is wrong.

GT: Russia was not defeated, and Western sanctions imposed on Russia have been proven ineffectual. Has the West's mentality of "defeating Russia" changed?

Mearsheimer: It's very clear that the economic sanctions have failed. It's quite remarkable. The Americans thought that once the war started, the sanctions on Russia, coupled with the Ukrainian army's early victories on the battlefield, would allow Ukraine to defeat Russia inside of Ukraine. The sanctions were considered to be a war-winning weapon against Russia. But they have almost completely failed. The Russian economy is doing very well. If anything, it's the European economies that have been hurt by the sanctions. The sanctions against Russia haven't worked.

Now, the question is, how is the US reacting to its failure to defeat Russia? Is the US facing up to reality and pushing the Ukrainians to negotiate a settlement with Russia? The answer is no. I think the US wants to continue the war for the foreseeable future in the hope that somehow Ukraine - with help from the West - will be able to reverse the situation on the battlefield and help Ukraine recover its lost territories. This is not going to happen. In fact, it's delusional thinking. It would make much more sense for the Ukrainians to try to work out a settlement with the Russians now. But that will not happen, because the West won't quit and it appears, at least for the time being, that the Ukrainians are not going to quit either.

GT: How do you comment on the current US policy toward China?

Mearsheimer: It's very important to emphasize that the engagement policy that the US employed toward China from roughly 1990 to 2017 is dead. We're not going back to engagement. The US has now adopted a containment policy. The US is determined to contain China's rise and that policy is not going to change. What this tells you is that the relationship between China and the US is going to be fundamentally competitive moving forward.

There is going to be cooperation between them for sure. China and the US do have common interests. So, they will cooperate on some fronts. For example, I believe there will be much trade between the US and China, although little of it will involve high-end technologies. The US will go to great lengths to slow down Chinese development of cutting-edge technologies, but otherwise, there will be a great deal of trade involving food stuffs, textiles, manufactured goods, and so on between China and the US. The two countries will also cooperate on issues like nuclear proliferation, and hopefully climate change.

But it's very important to understand that this cooperation will take place in the shadow of an intense security competition. That competition will dominate the relationship between China and the US, because they are the two most powerful states on the planet. Both countries will compete for power and will worry greatly about the balance of power between them.

Hopefully, both sides will go to great lengths to manage the competition in smart ways so that we don't end up in a shooting war. That would be disastrous. Nevertheless, it's going to be difficult to avoid conflict between the two sides, just as it was difficult to avoid fighting during the Cold War between the US and the Soviet Union. Thankfully, Moscow and Washington managed their intense security competition between 1947 and 1989 in ways that avoided actual shooting between the superpowers. We live in troubled times, and the dangers we face are not going to change for the better. If anything, things will get worse over time.

It was Donald Trump in 2017 who abandoned engagement with China and adopted a containment policy. After the 2020 election, where Biden defeated Trump and became president, he did not revert to engagement. Instead, he followed in Trump's footsteps and even doubled down on containment. So, whether Biden or Trump is in the White House in 2025 will not matter much for US-China relations.