Illustration: Xia Qing/ GT

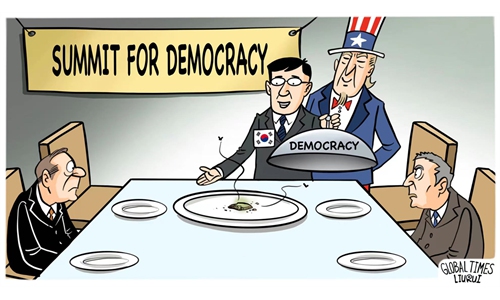

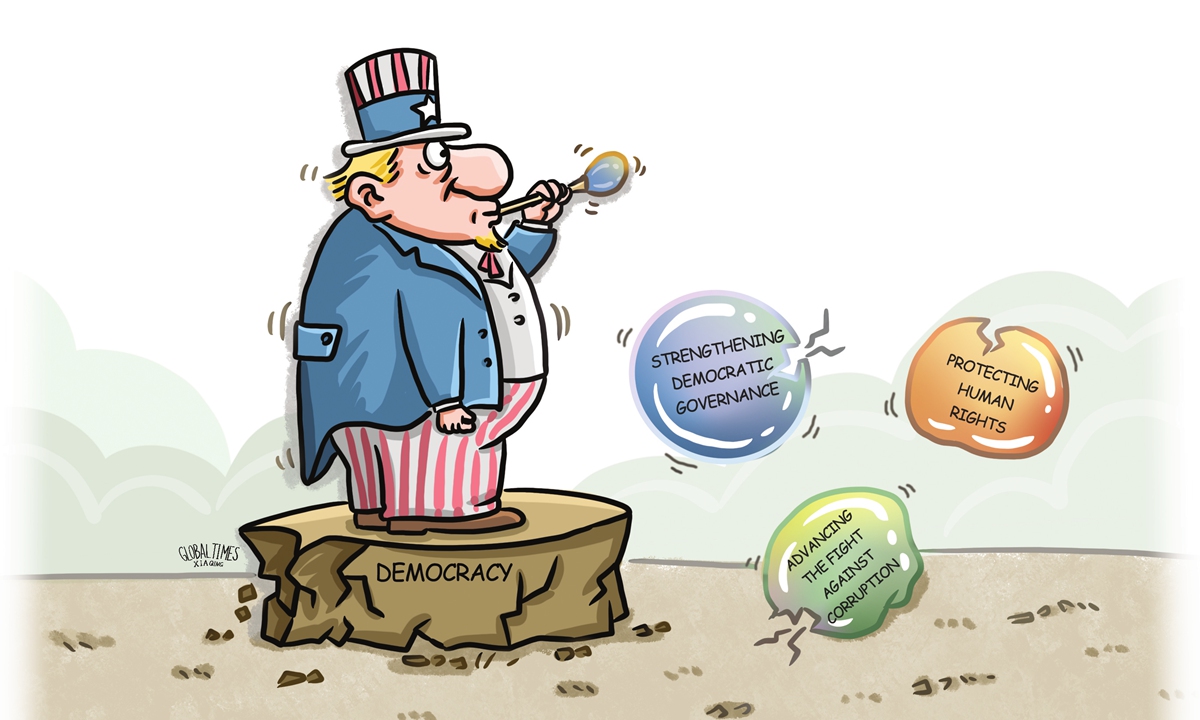

US Secretary of State Antony Blinken led an American delegation to attend the third Summit for Democracy in Seoul on March 18. According to the US State Department, the summit is essential because it "has brought together hundreds of leaders from governments, civil society, and the private sector committed to strengthening democratic governance, protecting human rights, and advancing the fight against corruption."

Critics might take US interest in "strengthening democratic governance, protecting human rights, and advancing the fight against corruption" more seriously if the US set the global standard in each of those areas. Put another way, while some countries are in worse shape than the US, America's chronic boasting about being the global champion in the aforementioned three concepts falls flat when findings from credible international organizations are evaluated.

Quite simply, for "strengthening democratic governance," the US is not the example other countries should be looking to. Consider data from the University of Wurzburg's Democracy Matrix, which places America at 36 out of 176 total countries. The matrix concludes that the US is a "deficient democracy," which is a bitter, but necessary, pill for often chest-thumping Americans to swallow. In the meantime, the Economist Intelligence Unit has for several consecutive years defined the US as a "flawed democracy."

In the fractured political climate in which the US finds itself, presidential candidates are hinting at a "bloodbath" if the November election ends up a certain way. This is generating domestic and international headlines because such comments are absolutely inconsistent with democratic practices. Yet, you and I need to remember that as we dig deeper into American democracy, concerns about denying citizens the right to vote and Americans' overall dissatisfaction with the democratic process affirm that the pillars of democracy are weakening. Left unstated is whether the American experiment in democracy has withered so much that a "bloodbath" could take place in just a few months.

America has much to do in the area of "protecting human rights." For example, courts limited human rights protections by striking down abortion rights and gun regulations and preventing the administration from ending exclusions of asylum seekers at the US-Mexico border. The Center for American Progress identified another problem with America's commitment to human rights: "Today in the United States, workers are not guaranteed a single paid day off by federal law, and many aren't even entitled to unpaid time." The US lags behind almost every other nation when it comes to maternity/paternity benefits; most workers get 12 weeks of unpaid leave when they are home taking care of a newborn.

America's long history of hatred toward the "other" because of their skin color, religious beliefs, or ethnic background has once again become a daily conversation. The attacks against Muslims at the beginning of this century and the recent attacks against Asians serve as evidence that human rights are not guaranteed in the US. The commitment to the "right to life" seems questionable when you consider the neonatal and educational deficiencies that exist throughout the country. It may sound harsh, but if you are a white, straight, middle- or upper-class American, you likely do not have to worry about your human rights. However, if you do not fit into those categories, you live in fear. This reality does not align with America's claim to be a beacon for human rights.

Finally, when it comes to "advancing the fight against corruption," America has much work to do. Transparency International's latest data place the US 24th out of 180 countries in the Corruption Perception Index. The lack of judicial independence is a major factor contributing to this ranking. The International Institute for Democracy and Electoral Assistance has also noted that the US continues to trail many of its global democratic partners in judicial independence. At present, one US elected political figure after another is linked to abusing their office for personal gain, furthering the belief that the wealthy or well-connected play by a different set of rules than the average citizen.

In announcing America's participation in the Summit for Democracy, Kelly Razzouk, a special assistant to the president and a National Security Council senior director for democracy and human rights, said, "We intend to highlight the ways that the United States continues to lead in strengthening democratic resilience and respect for human rights around the world."

But what about making improvements at home?

The author is an associate professor at the Department of Communication and Organizational Leadership at Robert Morris University. opinion@globaltimes.com.cn