Qu Changtao Photo: Courtesy of Qu Changtao

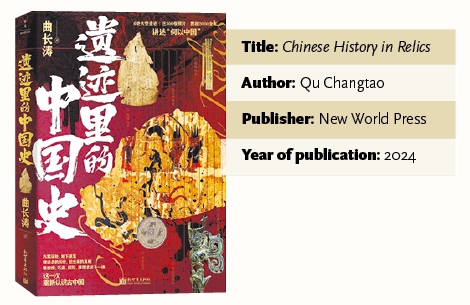

Although his first historical book Chinese History in Relics was just published in April 2024, writer Qu Changtao is no novice when it comes to ancient Chinese stories. With over 22 years of work experience as a newspaper journalist, Qu has been collecting historical and archaeological stories from all around the country.

Qu has been enchanted by Chinese histories that have simultaneously puzzled him. He told the Global Times that the more he delves into history, the more he realizes that it is still unfolding. Queries about the past motivated him to compile his recently published book, in which he has explored six of the most well-known Chinese archaeological ruins.

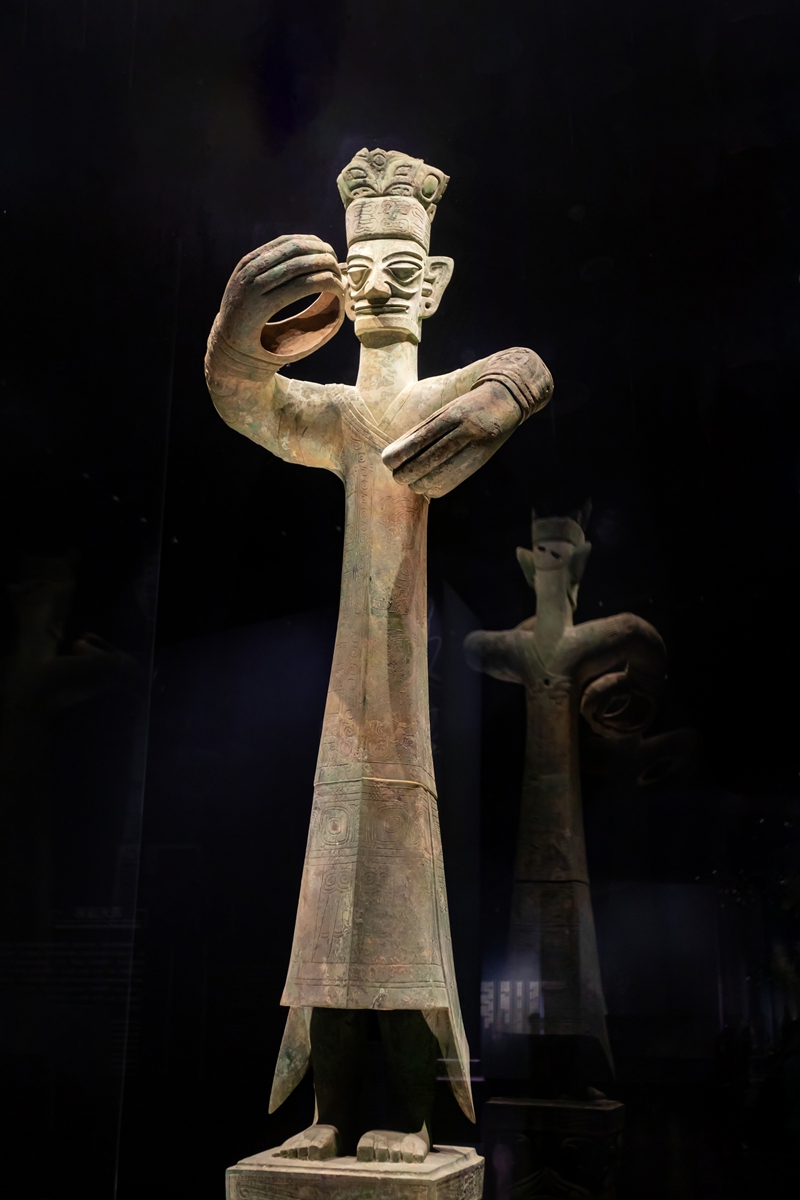

Chinese History in Relics includes six chapters. In chronological order, they unpack the mysteries of the Yinxu Ruins, the Sanxingdui Ruins, the tomb of King Anxi of Wei, the Shuihudi site, the Mawangdui site, and the Haihunhou tomb in Nanchang.

These ruins are scattered across different Chinese provinces including Sichuan, Henan, Hubei, and Jiangxi. They represent differences between Chinese historical periods spanning from the Warring States Period (475BC-221BC) to the Western Han Dynasty (206 BC-AD25).

Such sites were not chosen at random, but rather are interconnected through a timeline of 2,000 years of Chinese history. They showcase how the Chinese civilization evolved in certain periods when compared to its more than 5,000-year history.

"The Shang marks when the early civilization was forming gradually, and by examining the Qin and Han dynasties' sites, I found how historical legacies birthed the formation of the country's early cultural and social frameworks," Qu told the Global Times.

"I want readers to see how the Chinese civilization developed with diversities and continuity," the author emphasized.

Employing his journalistic storytelling skills, Qu's narration of history differentiates from the traditional chronological format as well as a stoic retelling of events. He packages his investigations as concise stories, giving them intriguing headlines such as "Tao Te Ching, the truth and the false."

He wrote about classic Chinese philosophical texts by referring to a silk Tao Te Ching manuscript that was discovered at the Han Dynasty Mawangdui site in 1973.

The Tao Te Ching was created by thinker Lao Tzu in the Spring and Autumn Period (770BC-476BC). The text has been interpreted numerous times, including by philosopher Wang Bi during the Three Kingdoms period (220-280). Wang's work is still the most popular Tao Te Ching interpretation to date, despite scholars debating its accuracy.

After interviewing experts and studying historical materials that he acquired from the local museum, Qu discovered, and was also convinced by a big distinction between the Han and Three Kingdoms period versions, with a more than 420-year gap.

In his book, he accounts for such distinctions, taking Tao Te Ching's first line "Dao Ke Dao, Fei Chang Dao" as an example, which is also present in Wang Bi's interpretation.

In a simple explanation, the opening line means that Dao (the ways to life) defines the universal law that cannot be explained explicitly with words, and conversely, any ways to life that can be explained explicitly are often not the most long-lasting or the real law to life.

The profound saying was documented differently on Han silk, where the line reads "Dao Ke Dao, Fei Heng Dao Ye."

The word "Heng," meaning "eternity" in Chinese, was presented to change the whole idea into describing that any way to life has its law, and there is no single eternal law that can guide one through his or her life until one learns to cope with the changing universe and society.

"I find the Han Dynasty one was more logically coherent and I'm convinced by it," Qu told the Global Times. He also added that stories like those in his books aim to open up readers' imaginations about the profound Chinese literary and philosophical legacies.

An oracle bone at the Yinxu Ruins Photo: VCG

Project continues

Such stories make Qu's book an interesting historical compilation that challenges readers' existing understanding of the sophistication of Chinese history.

In another story, he notes how the Qin people valued agriculture and invented an early ecological protection system by enacting laws such as prohibiting deforestation in spring - unless one has coffin-making requirements - as well as inventing strict criteria to assess agricultural officials.

A well-performing official in charge of stock farming who passed all four annual tests would receive a bottle of fine wine, 10 strips of dried pork, and also received an enviable 30 days of holiday.

Qu's depicted stories are seen as reflections of not only the history of dynasties, but also the history of how ancient humanity grew in China along with the changing times.

"I want readers to experience the vividness of Chinese culture through my writing," Qu said.

Published by New World Press, the book has received positive reviews from readers. "I wonder whether or not the book is this good," the author rather modestly questioned

He told the Global Times that his journey into Chinese history will not end in Chinese History in Relics since he is aiming to investigate around "10 to 20" historical sites and publish his findings in the future.

A bronze standing figure at the Sanxingdui Ruins Photo: VCG