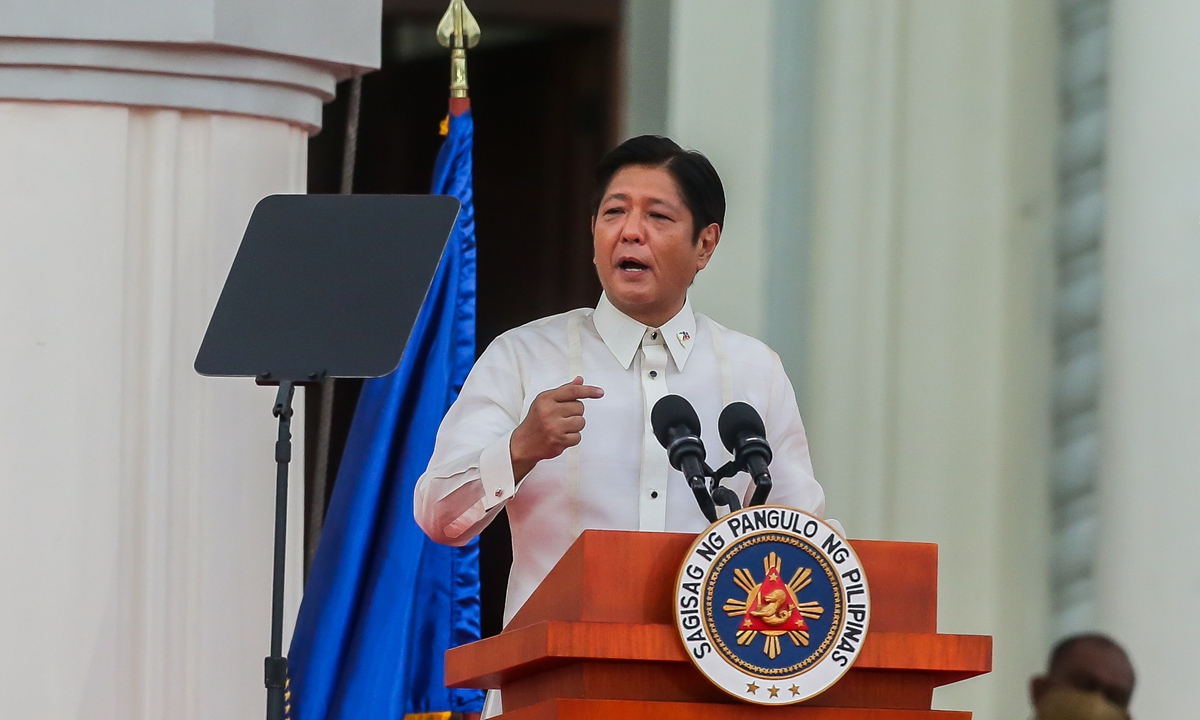

Ferdinand Romualdez Marcos, Jr. delivers his inaugural address as the 17th president of the Philippines at the National Museum in Manila in front of thousands of people on July 1, 2022.Photo:Xinhua

Since the beginning of this year, the Philippines has been intensifying its effort to make waves over Huanyan Dao (also known as Huangyan Island), through a series of moves ranging from groundlessly smearing Beijing for using cyanide to destroy the fishing area to rotational deployment of Philippine Coast Guard (PCG) and Bureau of Fisheries and Aquatic Resources (BFAR) ships in the waters.

The Philippine side has seemingly turned a blind eye to China's temporary special arrangement out of goodwill - which allows Filipino fishermen to carry out fishing activities near Huangyan Dao to support their livelihood - and repeatedly staging the real-life drama of The Farmer and the Viper - one of Aesop's Fables which shows kindness to evil will be met by betrayal.

If the Philippine side insists on taking advantage of China's goodwill arrangement as a bargaining chip for infringement, it will ultimately only result in a lose-lose situation, causing trouble for China, and leading the Philippines to pay a corresponding price.

Clear historical facts show that China was the first to survey Huangyan Island and exercise long-term effective administrative jurisdiction and development.

China conducted astronomical and geographical surveys of the South China Sea, including Huangyan Island, in the 13th century during the Yuan Dynasty (1279-1368). It shows that China discovered and exploited Huangyan Island in the Yuan Dynasty, to say the least.

In January this year, Philippine National Security Advisor Eduardo M. Año publicly tossed out the so-called "historical evidence" that in the early Spanish maps of the Philippines, including the 1734 Pedro Murillo Velarde Map, Huangyan Dao was always part of Philippine territory, and the Philippines exercises sovereign rights and jurisdiction over it. This official statement from the Philippines is pure nonsense.

As is well known, the modern territorial map of the Philippines is the result of a complex historical process that includes considerations of indigenous tribes, the Sultanate of Sulu, and successive colonial rules by Spain and the US.

The fundamental basis for determining the modern territorial boundaries of the Philippines includes the 1898 Treaty of Paris, the 1900 Treaty between the Kingdom Spain and the United States of America for cession of outlying islands of the Philippines, and the 1930 Convention between the United States of America and Great Britain delimiting the boundary between the Philippine archipelago and the State of North Borneo. But none of these treaties included Huangyan Dao.

Before the 1990s, the Philippines had never challenged China's sovereignty and jurisdiction over Huangyan Dao. In the late 1990s, the Philippines advanced its territorial claim over Huangyan Dao on the grounds of geographic proximity and on the excuse that Huangyan Dao is located within the 200 nautical miles of the Philippine EEZ according to its one-sided interpretation of UNCLOS.

Since May 1997, the Philippines revealed its intention to occupy China's Huangyan Dao. In 1999, the Philippine Navy deliberately ran its landing craft BRP Sierre Madre aground on the Ren'ai Jiao, using a hull leak repair as an excuse, and stayed there with regular rotated soldiers, refusing to withdraw ever since. In 2009, the Philippines amended the Philippine Territorial Sea Baselines Act to include Huangyan Dao into its territory. In April 2012, the Philippine Navy made a provocative arrest of Chinese fishermen working in the Huangyan Dao waters in what was later known as the Huangyan Dao Incident.

After the incident, China began to normalize patrols around Huangyan Dao, maintain orderly fishing activities, strengthen marine ecological protection, and prevent a recurrence of maritime crises. However, since 2012, the Philippines has seen the gradual spread of populism, nationalism, and revanchism triggered by this incident, with some factions in the government and society vowing to return to Huangyan Dao.

During former Philippine president Rodrigo Duterte's administration, China and the Philippines conducted friendly consultations and a tacit understanding and temporary arrangements at the operational level for Filipino fishermen in the waters near Huangyan Dao, yet Philippine fishing boats are not allowed to enter the lagoon, fish for rare marine life.

Despite deliberate distortions and smears by the Philippines, the fact that a significant number of Filipino fishermen benefit from this arrangement cannot be denied. At the same time, both countries have fully utilized bilateral mechanisms to engage in consultations on the South China Sea issue and communication between coast guard agencies to effectively address differences and crises related to Huanyan Dao. Although this cannot fundamentally resolve the contradictions and differences between China and the Philippines, the agreement has played a positive role in maintaining overall stability in the maritime situation.

However, starting in the second half of 2023, the Ferdinand Marcos Jr. administration, influenced by maritime expansionism, placed Huanyan Dao and Ren'ai Jiao as a prioritized diplomatic agenda for the Philippines, turning the impulse to return to Huangyan Dao into actual maritime and diplomatic actions.

The Philippine Navy, PCG, and BFAR took turns in attempting to forcibly making breakthroughs in the waters under the guise of providing food and fuel supplies to fishermen, trying to enter the lagoon of Huangyan Dao. The Philippines' proactive actions have kept China and the Philippines on the edge of repeating the 2012 incident since the second half of last year, with China Coast Guard ships and Philippine military and government vessels engaging in low-intensity friction in the waters.

The Marcos Jr. administration's distortion of right and wrong shows its fundamental intentions. First, the Marcos Jr. administration harbors the fantasy of "regaining control" of Huangyan Dao, to curry domestic voter approval, thereby rebuilding the prestige of himself and his family in the Philippines, especially shaping the positive image of the president as "tough," "patriotic," and "wise." Second, the tough actions at Huangyan Dao also meet the preferences of the PCG, Philippine Navy, and other government agencies. Third, the Philippines also sees its actions at as an important measure to support the US' Indo-Pacific Strategy framework to contain China at sea. It also reflects the Marcos Jr. administration's tendency to lean on the US to flex muscles on the South China Sea issue.

China's temporary special arrangement over the recent past, the consensus and tacit understanding with the Philippines have eliminated the high costs of frequent maritime standoffs and diplomatic confrontations, as well as the negative spillover effects. This has provided a stable environment for Filipino fishermen to engage in fishing activities around Huangyan Dao, which has been truly a win-win situation.

Particularly benefiting from increased political mutual trust and smooth diplomatic channels, the two countries successfully explored a new path of cooperation in maritime fisheries from 2017 to 2019. China's provision of fish fry, aquaculture facilities, and technical training assistance has brought tangible benefits to Filipino fishermen.

On the contrary, the Marcos Jr. administration's hardline policies, expansionist tendencies, and "unconventional" style of behavior have disrupted the tacit understanding between Beijing and Manila, greatly weakened the foundation of political mutual trust, and turned the win-win cooperation between China and the Philippines on Huangyan Dao into a zero-sum game, which is tantamount to turning back the wheel of history.

The normalization of the Philippines' intruding actions in the adjacent waters of Huangyan Dao has replaced "dialogue and cooperation" with "confrontation" as the main approach for China and the Philippines to address their relevant contradictions. The Marcos Jr. administration's aggressive actions at sea may earn diplomatic "applause" from the US and the West, but the frequent and tense confrontations on the ground only drain significant military and diplomatic resources from both China and the Philippines, apart from wasting economic investments, escalating the risk of unforeseen maritime incidents, and yielding no valuable benefits.

At the same time, the unilateral destruction of the consensus and tacit understanding on Huangyan Dao by the Philippines has weakened the foundation of mutual trust between the two sides. As a result, South China Sea tension between China and the Philippine has risen to near record levels. While meetings between Chinese and Filipino leaders and joint statements between the two governments have repeatedly confirmed that the South China Sea issue is not the entirety of China-Philippines relations, the Marcos Jr. administration has prioritized the contradiction on Huangyan Dao as the top issue in handling relations with China and foreign affairs, seriously deviating from the previous consensus of the two countries.

The Philippine government often talks about the livelihood of fishermen, but its actions are tinged with the taste of "sophisticated selfishness." Using "fishermen's resupply" as a cover to "regain control" of Huangyan Dao reveals its true intention, satisfying only the needs of some politicians. The fishermen have to face political and security risks and economic losses in tense maritime frictions. Moreover, the aggressive stance of the Philippine government also forces China to reconsider the arrangements for the fishing order on Huangyan Dao.

If the Philippines continues to fantasize about staging a "Farmer and the Viper " scenario, using the so-called fishermen's resupply as a pretext to actually gain territorial sovereignty, then China may have no better choice but to take escalated control and management measures, including lifting the temporary arrangements, to prevent the situation from escalating and avoid a repeat of the 2012 incident.

The author is director of the World Navy Research Center at the National Institute for South China Sea Studies. opinion@globaltimes.com.cn