LIFE / ATTITUDES

China-Serbia friendship, shared aspirations

Illustration: Liu Xiangya/GT

Upon arriving in Belgrade amid the warm breezes of early May, I was greeted by the cordiality of Serbians and given a glimpse into the "ironclad" friendship of China and Serbia.

The shuttle van driver, after learning that myself and two other reporters were from China, proudly introduced the beautiful landscape and landmark buildings we drove pass.

Located at the confluence of the Danube and Sava rivers, Serbia has a European city view with baroque, classicism buildings and grand Orthodox churches, while the socialist period left some commune mansions. Some ruins from war time have not been demolished, yet brand new, glass-wall skyscrapers have been built.

The driver also offered to show us some important places marking the friendship between the two countries such as the Pupin bridge on the Danube, which was built with China's support and nicknamed the "China bridge," and the memorial for the Chinese Embassy to Yugoslavia that was bombed by NATO in 1999. When showing us the city, he pointed at billboards of Chinese brands and institutions like Huawei, Xiaomi, the Bank of China, and so forth.

Though I had a general concept of the sound relationship between the two countries, such hospitality was beyond my expectations.

On the way from Belgrade Nikola Tesla Airport to the city center, Chinese and Serbian national flags fluttered in the sunny weather, yet I thought they were part of some diplomatic proprieties. However, after I found that the entire capital was ornamented by Five-Star Red Flags and welcome banners of different sizes at every corner, I was convinced of Serbia's warmhearted embrace for friends from afar.

This strong sentiment of brotherhood was repeatedly reinforced in the days to follow.

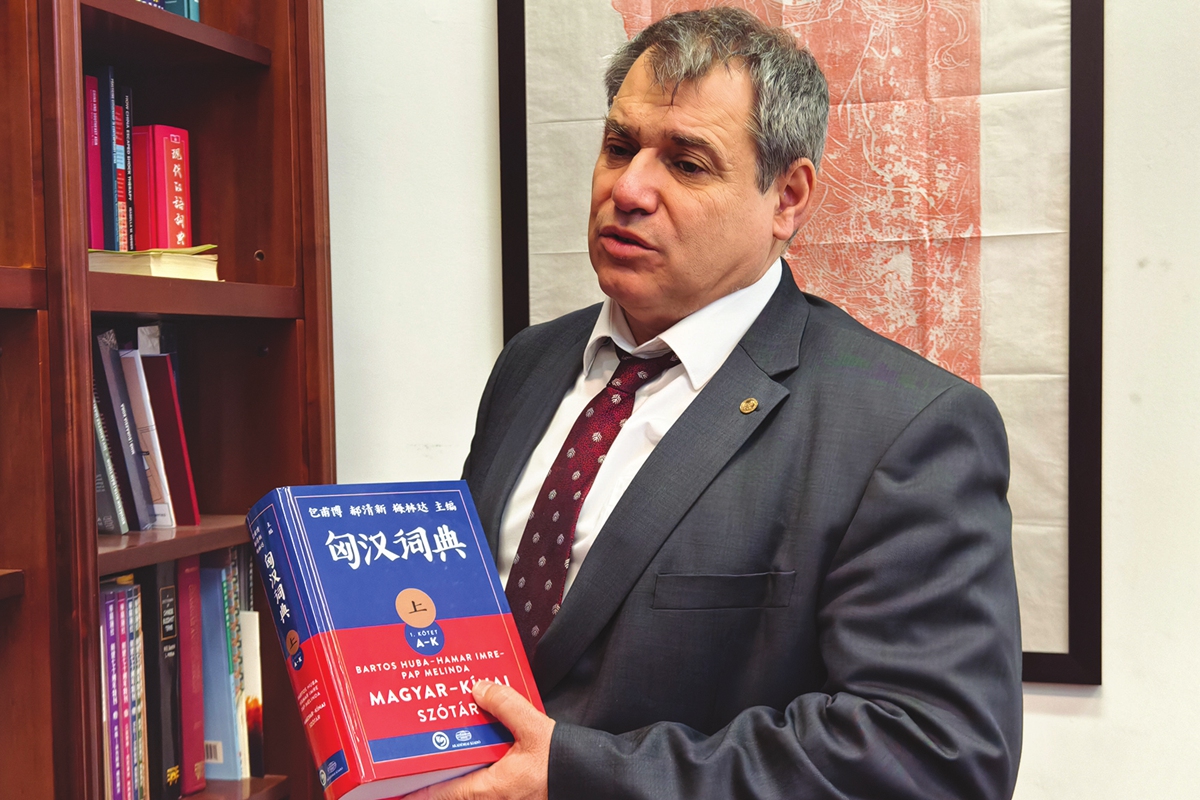

The newly opened China Cultural Center was the first stop of all my interview locations. Knowing it was Orthodox Easter, I was concerned that students might hesitate to come to the center in the middle of a six-day holiday, May Day and Easter combined.

I was totally wrong.

They were more than willing to help. Police officer Danijela Radanovic came off a 12-hour night shift and gave us two hours of her precious rest time, even though she had another 12-hour shift that night. The cultural center stands beside the memorial for the old embassy. Noting that the bilateral friendship was forged with blood at that time, Radanovic said the bombing 25 years ago was a major part of her childhood memories.

Another student, Vladimir Roglic, who had quite some knowledge of Chinese history, said Chinese people suffered in the 19th to early 20th centuries, and Serbians had also suffered a lot as a result of frequent external conquest due to their nation's strategic position.

"But our peoples are tough and can always stand up again from ruin. We have many similarities and we understand each other," Roglic said.

Yet one does not have to dig into history to understand the friendship between the two countries, as contemporary examples are vivid and abundant.

When doing street interviews with passersby about how they felt about being called "sai tie" in Chinese, which can be translated to "Serbian ironclad friend," China's medical aid to Serbia in the early days of COVID pandemic was frequently mentioned.

Some shared their experiences with Chinese business partners or friends, or visiting China themselves. Big smiles and bursts of laughter fully spoke of the joy and delight China has brought them.

Roglic, a Tai Chi practitioner for more than 10 years, said he has dreamed of living on the Wudang Mountain and following real masters to improve his techniques. His classmate Jana had visited China, where she felt really supported and safe.

When a young woman on the street said "ganbei" (cheers) when she was asked to say something in Chinese, I realized another similarity between our two countries could be an interest in liquor.

A young man who did not give his name said China's help in upgrading Serbia's roads, highways, high-speed rail links to Hungary and other infrastructure.

I took a ride on the Belgrade-Novi Sad section of the railroad, which has handled 7 million trips over its two years of operation. With a design speed of 200 kilometers per hour, the train is stable, comfortable and cuts the original travel time from one and a half hours down to 36 minutes.

A one-way ticket costs about six euros ($6.50) while a round trip is eight euros, an "inexpensive fare" one can conveniently pay by app, with a transport card or at the station's ticket office.

A high school student on the train told me he studies in Belgrade and was taking the train to visit his parents in Novi Sad. Commuters also take the trains for work, while the low platforms built by the Chinese contractors allow cyclists to easily bring their bikes on the train.

During the Easter holiday, many locals and tourists take the train to Novi Sad, the second largest city in Serbia and which is renowned for art, music and the idyllic stretch of the Danube.

The high-speed train has brought in more tourists, made two-city life possible for locals and, when the whole 352 kilometers to Budapest are completed in 2026, is sure to further enhance Serbia's connectivity and boost its economy.

Aleksandra Milosavljevic, a Serbian engineer, told me that working on the project, she has not only learned engineering and management skills, but also made real friends with her Chinese colleagues.

It is through the interactions of ordinary people and tangible fruits of cooperation that the China-Serbia friendship has been forged and prospers.