Why does US refuse to admit forcing Japan, the Netherlands to 'decouple'?: Global Times editorial

Illustration: Chen Xia/GT

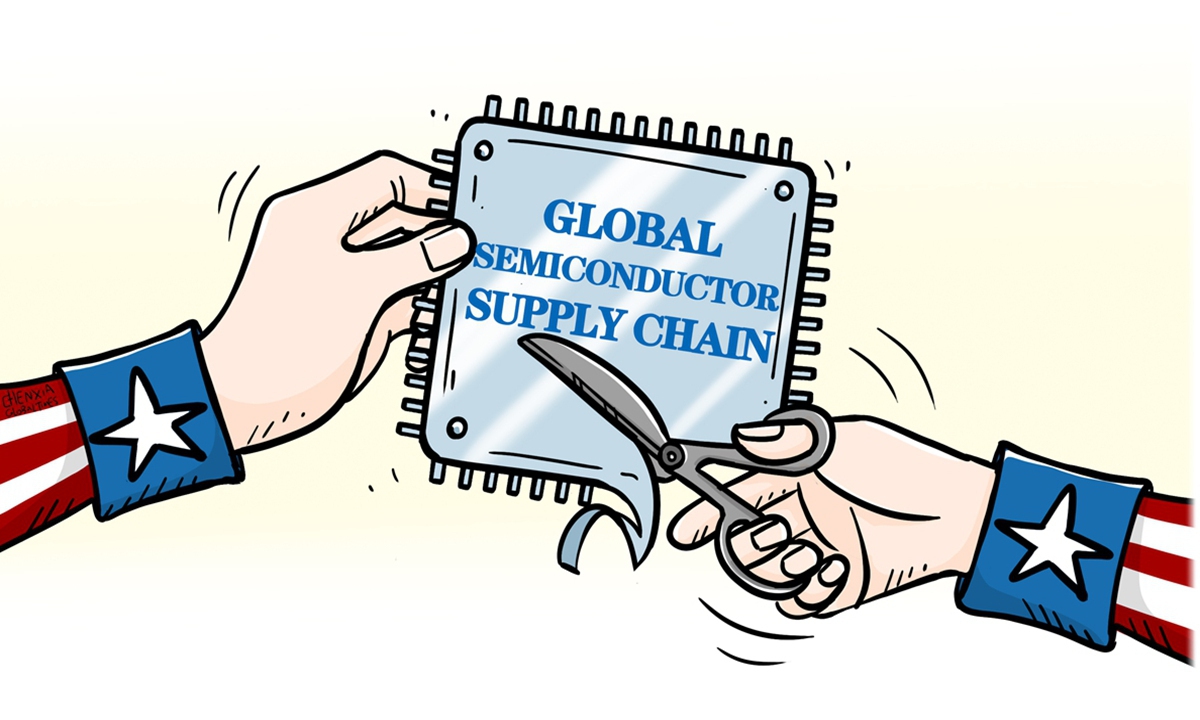

The US shows no respect for fixed diplomatic protocols and arrangements, sending officials to countries like Japan and the Netherlands to demand their cooperation in imposing restrictions on certain high-tech industries in China. This is a repeated occurrence. US Under Secretary of Commerce for Industry and Security Alan Estevez visited Japan and the Netherlands a few days ago to request both countries further limit China's ability to produce cutting-edge semiconductors. Perhaps worried that doing so will encounter some resistance, the US side refused to comment on the reports.As early as March of this year, Nikkei Asia reported that the US government had requested Japan and the Netherlands to expand their restrictions on semiconductor-related exports to China. Perhaps because Japan and the Netherlands both chose "soft resistance" at that time and did not fully follow the US' lead, the US government sent a high-ranking official to exert pressure once again. This approach of sending high-ranking officials to pressure allies shows that the US' coercion of allies to implement measures to contain China's semiconductor industry is unpopular.

In fact, the US has forced other countries to cooperate with its "small yard, high fence" and "decoupling" policies toward China under the name of "rallying allies," but it has not achieved the expected results. Bloomberg's analysis pointed out that the US government has been limiting China's ability to buy and produce advanced semiconductors for years, under the pretext of national security, but the results have not achieved the desired outcome, as companies like Huawei are making significant technological breakthroughs on their own. Gregory Allen, director of the Wadhwani Center for AI and Advanced Technologies at the Center for Strategic and International Studies, also pointed out that "the US is the most critical player in the global semiconductor equipment industry, but it's far from the only country that matters. Japan and the Netherlands are also key providers of semiconductor equipment. The Netherlands and Japan have restrictions on exports but not on servicing, and that's a critical limitation in the overall technology controls architecture."

However, some in the US insist on protectionism. In their view, the reason for the lackluster effect of the "small yard, high fence" strategy is not because building fences is wrong, but because there are loopholes in the fences that need to be addressed by pressuring allies to "fill in the loopholes" in order to effectively chokehold China's semiconductor industry development.

Since January 2023, under pressure from the US, Japan and the Netherlands have reached an agreement to restrict exports of advanced chip-manufacturing equipment to China. However, there has been strong opposition and resistance within both countries. For example, Takakage Fujita, secretary-general of the Association for Inheriting and Propagating the Murayama Statement, believes that as a member of Asia, Japan should adopt a rational policy toward China and not blindly follow the US in engaging in group confrontation in the Asia-Pacific region. The Nikkei newspaper has also pointed out that Japan, which has an alliance with the US, is required to adopt the same level of control as the US, leading Japanese companies to lose the huge Chinese market they have always relied on. The Dutch political arena has also heard opposition to the unilateral change of rules even by allies.

There are not only dissatisfactions with the selfish and hegemonic practices of the US, but also concerns about the damage to domestic industries and national interests caused by being forced to follow the US in decoupling from China. However, due to hegemony from the US, the governments of Japan and the Netherlands can only "feel angry but dare not to speak out," and can only engage in "delayed resistance," which is only a temporary solution.

It is worth noting that the US has recently hinted that Japan should also "take sides" in the field of electric vehicles (EVs) against China. Indeed, China's EV industry has developed rapidly in recent years, and many Japanese car companies have also felt the pressure. However, blindly following the US in decoupling from China in the EV sector, like in the semiconductor sector, does not actually serve Japan's interests. On the one hand, EVs currently account for a small portion of the Japanese new car sales market, and have not reached a level that would "destroy" the Japanese automotive industry. On the other hand, the economies of China and Japan are intertwined. While it may seem simple for Japan to raise tariffs on China along with the US, the result will surely be harmful to others and detrimental to Japan itself. A recent survey by Reuters on June 20 showed that more than 60 percent of Japanese companies see no need for their government to follow the US in raising tariffs on Chinese imports.

The US' actions of coercing other countries to impose semiconductor controls on China are seriously hindering the global semiconductor industry development, impeding technological progress, and will ultimately become a "boomerang" threatening the future of American technology. Relevant countries should distinguish right from wrong, resolutely resist coercion, jointly uphold a fair and open international economic and trade order, and safeguard their own long-term interests.