ARTS / CULTURE & LEISURE

A new milestone for returning relics home

"It is so difficult... it is a difficult system..."

After the International Conference on the Protection and Return of Cultural Objects Removed from Colonial Contexts concluded, the British speaker was surrounded by representatives from several countries whose relics had been looted by foreign forces, including one from Yemen who spoke with a pained look upon her face.

"This conference is very, very important," Armen Mkhitaryan from the Armenian Chinese Partnership Center told the Global Times with a serious look upon his face while talking about the conference, which was held in Qingdao, East China's Shandong Province, as a supporting event of the 2nd Council Meeting of the Alliance for Cultural Heritage in Asia.

He said that just like China, Armenia also has lost cultural relics overseas, some of which are on display at the British Museum.

Melina Antoniadis, a Canadian lawyer specialized in public international law and founder of a London-based consultancy company focusing on the return of cultural heritage, told the Global Times on Thursday that as half Greek and half Cambodian herself, her two heritages are directly impacted by this.

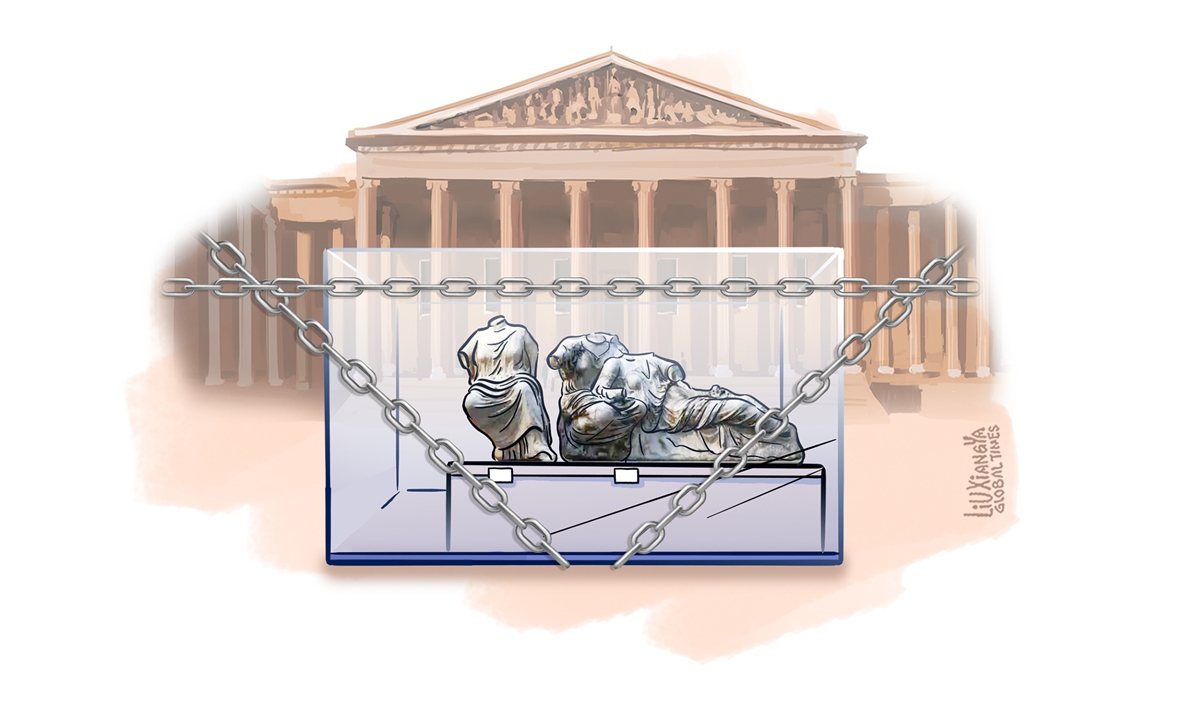

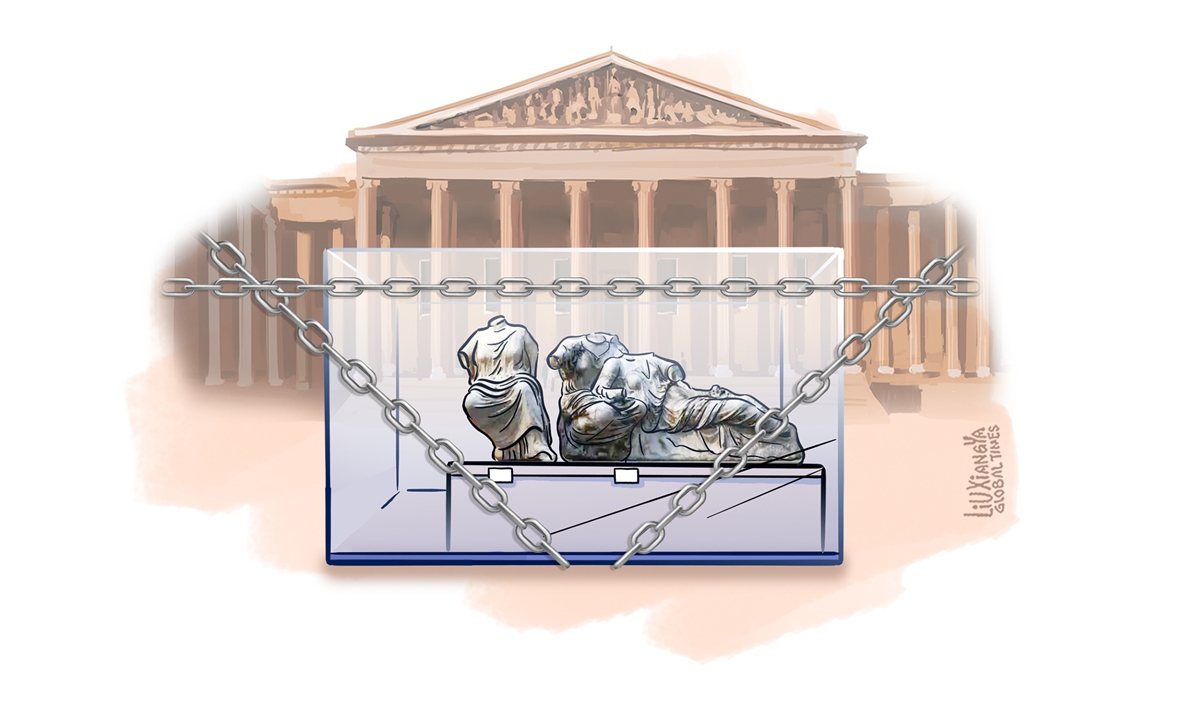

"I'm also advising this organization on the return of the Parthenon sculptures from the British Museum. The Parthenon sculptures are one of the biggest cases for this issue and I know that a lot of countries currently have their eyes turned to this," she said.

Indeed, the return of artifacts looted by colonial forces has become a highlight of international affairs as more countries with lost heritage are raising their voices only to receive silence from certain museums in response.

Why is it so difficult to return these stolen relics?

After talking with many experts and scholars of international law, the Global Times found the biggest barrier is that many lost cultural relics have passed their prosecution date.

"There is messy legislation which sometimes prohibits them from returning artifacts completely, but they can enter into loan agreements," Antoniadis said, adding that only cooperation can solve this problem.

"It's not about just emptying all the museums or asking the possessor countries to return all the lost cultural relics," Jude Nilan Cooray, a cultural scholar from Sri Lanka, told the Global Times on Thursday.

He further explained that some lost cultural relics could play a role in introducing the culture and history of Sri Lanka to overseas audiences by staying where they are, while highly precious cultural relics, like the 8th century gilded bronze standing figure of a female deity currently displayed at the British Museum, must be returned as they represent the "dignity of our nation."

Many experts who participated in the event told the Global Times that with the rapid development around the world, new actions need to be taken for countries to advance with the times rather than be "stuck in their old ways," adding that the released Qingdao Recommendations for the Protection and Return of Cultural Objects Removed from Colonial Contexts or Acquired by Other Unjustifiable or Unethical Means (Qingdao Recommendations) is coming "at the right time."

The Qingdao Recommendations calls on all countries to engage in open and inclusive international dialogue, beyond the scope of existing international conventions, to facilitate the return of cultural relics to their countries of origin in order to strengthen social cohesion and the inter-generational transmission of cultural heritage.

Olivia Whitting, head of Cultural Heritage at the Art Loss Register, told the Global Times on Thursday that she was very impressed by the recommendations that spoke about collective collaboration and reaching a consensus through research, noting that this should not take place in just one country, but all countries around the world.

"I think without that consensus, it's difficult to move forward. And I think that allowing people in other countries to research and to look into the items themselves, but then allow the country that is the original owner to really make the decision as to what happens to the item, is really crucial," she said.

After participating in the event, another "big surprise" was that there were quite a few scholars, officials and civilians from countries possessing looted relics who held a supportive and friendly attitude toward the return of these items.

Whitting told the Global Times that as a British person, she can feel that the British public is becoming more open to returning looted relics and "acknowledging the role of colonialism."

During the conference, professor Donald John Harper from the University of Chicago and officials from China's National Cultural Heritage Administration held a handover ceremony for the Physical Evidence of the Circulation of the Zidanku Silk Manuscripts, an ancient document that dates back to the Chu State of the Warring States Period (475BC-221BC) and were lost in the US. This piece of evidence is an outer packaging box cover that once contained the fragments of the Zidanku Silk Manuscripts. The manuscripts themselves were not included as the professor did not own them.

"My goal is to do everything I can to help the process with the result that the silk manuscripts return to China... I think this kind of event, such as today, is exactly the right thing," Harper told the Global Times on Thursday.

The author is a reporter with the Global Times. life@globaltimes.com.cn

After the International Conference on the Protection and Return of Cultural Objects Removed from Colonial Contexts concluded, the British speaker was surrounded by representatives from several countries whose relics had been looted by foreign forces, including one from Yemen who spoke with a pained look upon her face.

Illustration: Liu Xiangya/GT

During the event on Thursday, guests wearing simultaneous interpretation equipment listened to speeches from representatives of different countries very carefully, hoping to find potential opportunities for cooperation or solutions to bring back their looted cultural relics."This conference is very, very important," Armen Mkhitaryan from the Armenian Chinese Partnership Center told the Global Times with a serious look upon his face while talking about the conference, which was held in Qingdao, East China's Shandong Province, as a supporting event of the 2nd Council Meeting of the Alliance for Cultural Heritage in Asia.

He said that just like China, Armenia also has lost cultural relics overseas, some of which are on display at the British Museum.

Melina Antoniadis, a Canadian lawyer specialized in public international law and founder of a London-based consultancy company focusing on the return of cultural heritage, told the Global Times on Thursday that as half Greek and half Cambodian herself, her two heritages are directly impacted by this.

"I'm also advising this organization on the return of the Parthenon sculptures from the British Museum. The Parthenon sculptures are one of the biggest cases for this issue and I know that a lot of countries currently have their eyes turned to this," she said.

Indeed, the return of artifacts looted by colonial forces has become a highlight of international affairs as more countries with lost heritage are raising their voices only to receive silence from certain museums in response.

Why is it so difficult to return these stolen relics?

After talking with many experts and scholars of international law, the Global Times found the biggest barrier is that many lost cultural relics have passed their prosecution date.

"There is messy legislation which sometimes prohibits them from returning artifacts completely, but they can enter into loan agreements," Antoniadis said, adding that only cooperation can solve this problem.

"It's not about just emptying all the museums or asking the possessor countries to return all the lost cultural relics," Jude Nilan Cooray, a cultural scholar from Sri Lanka, told the Global Times on Thursday.

He further explained that some lost cultural relics could play a role in introducing the culture and history of Sri Lanka to overseas audiences by staying where they are, while highly precious cultural relics, like the 8th century gilded bronze standing figure of a female deity currently displayed at the British Museum, must be returned as they represent the "dignity of our nation."

Many experts who participated in the event told the Global Times that with the rapid development around the world, new actions need to be taken for countries to advance with the times rather than be "stuck in their old ways," adding that the released Qingdao Recommendations for the Protection and Return of Cultural Objects Removed from Colonial Contexts or Acquired by Other Unjustifiable or Unethical Means (Qingdao Recommendations) is coming "at the right time."

The Qingdao Recommendations calls on all countries to engage in open and inclusive international dialogue, beyond the scope of existing international conventions, to facilitate the return of cultural relics to their countries of origin in order to strengthen social cohesion and the inter-generational transmission of cultural heritage.

Olivia Whitting, head of Cultural Heritage at the Art Loss Register, told the Global Times on Thursday that she was very impressed by the recommendations that spoke about collective collaboration and reaching a consensus through research, noting that this should not take place in just one country, but all countries around the world.

"I think without that consensus, it's difficult to move forward. And I think that allowing people in other countries to research and to look into the items themselves, but then allow the country that is the original owner to really make the decision as to what happens to the item, is really crucial," she said.

After participating in the event, another "big surprise" was that there were quite a few scholars, officials and civilians from countries possessing looted relics who held a supportive and friendly attitude toward the return of these items.

Whitting told the Global Times that as a British person, she can feel that the British public is becoming more open to returning looted relics and "acknowledging the role of colonialism."

During the conference, professor Donald John Harper from the University of Chicago and officials from China's National Cultural Heritage Administration held a handover ceremony for the Physical Evidence of the Circulation of the Zidanku Silk Manuscripts, an ancient document that dates back to the Chu State of the Warring States Period (475BC-221BC) and were lost in the US. This piece of evidence is an outer packaging box cover that once contained the fragments of the Zidanku Silk Manuscripts. The manuscripts themselves were not included as the professor did not own them.

"My goal is to do everything I can to help the process with the result that the silk manuscripts return to China... I think this kind of event, such as today, is exactly the right thing," Harper told the Global Times on Thursday.

The author is a reporter with the Global Times. life@globaltimes.com.cn