ARTS / ART

Cultural exploration not excuse for looting

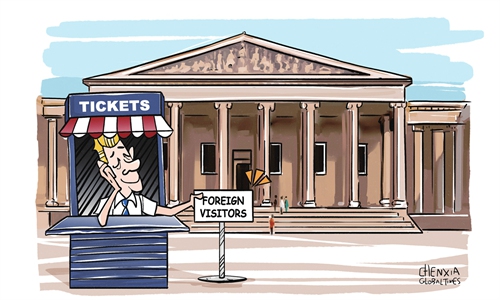

Illustration: Liu Xiangya/GT

It is obvious that being the victim of theft didn't help the British Museum reflect on returning the relics in its collection looted from other countries, at least not for some historians.

An article titled "Chinese artifacts in repatriation row were 'given willingly' to British Museum" was published in the British Newspaper The Guardian, which claimed to reveal that many artifacts in British Museum were not the result of imperial plunder.

The article cites "evidence" found by US historian Justin M. Jacobs, who suggests that the Chinese government "willingly and enthusiastically helped them remove these treasures from their land" because they wanted closer ties with the West and appreciated new scholarship.

While the evidence is said to be covered in his book, Jacobs does not clearly elaborate on the sources or context of this "evidence" in the article. He only mentions a letter from a Chinese magistrate to Aurel Stein in 1914, which states, "Your practice of archaeology with a stunning perseverance and thoroughness that is unheard of."

However, the identity of this Chinese magistrate is unclear, and Aurel Stein, the British-Hungarian archaeologist who acquired thousands of Chinese antiquities that ended up in the British Museum and other collections, is also unrecognized by modern Chinese scholars.

"At that time, Stein bought many cultural relics from Taoist priest Wang Yuanlu at a low price, under the pretext of so-called cultural exploration. However, he clearly knew that the prices were significantly below their actual value. This behavior itself is neither legitimate nor ethical," Huo Zhengxin, a law professor at the China University of Political Science and Law, told the Global Times on Monday.

Huo also noted that this took advantage of the funding shortages for cultural preservation at the time, as well as Wang's limited awareness.

Huo also emphasized that during that historical period, various warlords were vying for power. Some warlords, for their own benefit and to gain support from the West, sold cultural relics at low prices, which cannot represent the official stance of China.

Isn't this another form of "plundering?"

Therefore, the logic of seeing these artifacts as diplomatic gifts as "these items did not have the priceless value we attribute to them today...," is ridiculous. Whether artifacts should be returned today is based on current value judgments on historical rights, and the assessment of value should also be determined by the place of origin of the artifacts. The so-called Chinese authorities in the letter did not have the authority to approve the removal of these relics and their actions do not represent contemporary Chinese views, as such "evidence" contributes nothing to the moral question of whether the British Museum's artifacts should be returned to China today.

It's also worth noting that most Chinese artifacts flowed into Britain during a period when China was suffering from endless wars. For example, the Great Bell of Tianning Temple was looted by British invaders during the First Opium War (1840-42) and presented to Queen Victoria, who "donated" it to the British Museum in 1841.

The current international situation has changed, but this historian is still using colonial-era thinking to judge the current ownership of artifacts, which is meaningless.

In fact, no matter if these relics were looted or gifted, multiple pieces of evidence already show that these artifacts have rich historical value today, and returning the artifacts to their roots is the correct historical choice.

In recent years, there have been continuous calls for the British Museum to return artifacts, including the Parthenon Marbles (also known as the Elgin Marbles), the Rosetta Stone, and the Benin Bronzes.

At the International Conference on the Protection and Return of Cultural Objects Removed from Colonial Contexts held in Qingdao, East China's Shandong Province last week, many experts from Canada, Nigeria, and other countries told the Global Times that with today's rapid global development, new actions need to be undertaken for countries to advance with the times rather than be "stuck in their old ways." They called on all nations to participate in open and inclusive international dialogue, extending beyond existing international conventions, to enable the return of cultural artifacts to their countries of origin.

Even a columnist from The Observer, Martha Gill, raised doubts about so-called cultural exchange as an excuse for not returning the artifacts, noting that the central problem here is that "These objects are not just a record of colonial oppression and historic crimes but, to many, the thing itself perpetuated." "This compromises a museum's role as an educator: It must tiptoe round the subject, talking of 'uncomfortable histories' that still need to be 'explored,'" Gill commented.

Only one side of this war is backed by facts, while the arguments against restitution, one by one, are crumbling into dust.

The author is a reporter with the Global Times. life@globaltimes.com.cn