ARTS / CULTURE & LEISURE

Uniqueness of the Beijing Central Axis

The inscription of the Central Axis of Beijing on UNESCO's World Heritage List narrates a Chinese story of enduring civilization, blending the ancient with the modern.

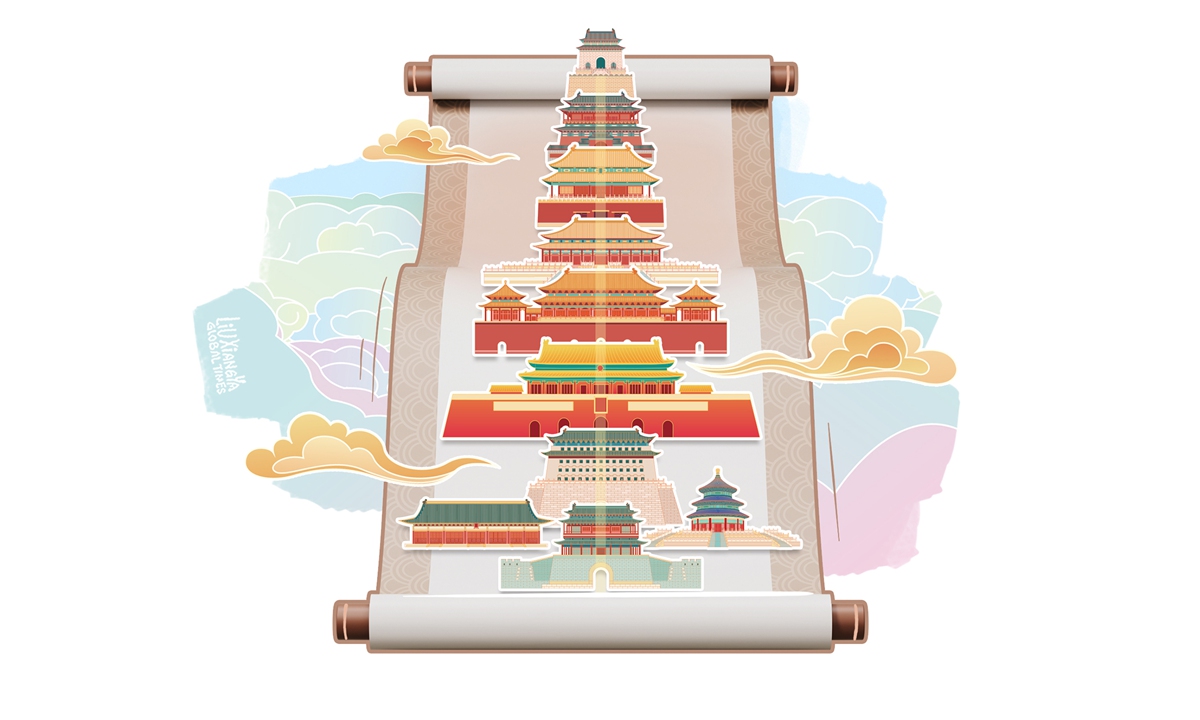

The Central Axis, located in the heart of the old city, stretches 7.8 kilometers in length north to south.

Continuously refined over more than seven centuries, it was first established in the 13th century and took shape in the 16th century, forming a holistic, orderly, and majestic urban central architectural complex.

It has witnessed the continuous evolution of the spirit of Chinese civilization in constructing the order of Chinese life and the form of the capital city.

The uniqueness of the Central Axis is reflected in the traditional Chinese philosophy and cultural spirit it embodies.

This philosophy and cultural spirit expressed through the layout and spatial form of the Central Axis has continuously determined and influenced the evolution of the entire capital city.

In addition, the axis showcases a unique architectural form and urban landscape, giving it a prominent place on the World Heritage List.

The Tian'anmen Square complex, a 20th-century architectural masterpiece, continues the traditional philosophy and planning ideas reflected in the Central Axis, demonstrating the continuity and unity of Chinese civilization.

As the most representative achievement of the mature period of Chinese capital city planning, the Central Axis gathers aspects from the core central axis designs of all Chinese dynasties.

It is the only extant example of a complete central axis architectural complex.

For example, the central axis architectural complexes in cities like Chang'an, the capital city of the Tang Dynasty (618-907), and Bianjing, the capital city of the Northern Song Dynasty (960-1127), reflect different stages of the development of the central axis of a capital city.

However, most of these cities' central axis architectural complexes have disappeared to a certain extent over time, while the Beijing Central Axi is well preserved and retains the marks of various eras.

Meanwhile, in East Asia, ancient capitals outside of China were mostly influenced by Chinese culture in terms of planning concepts and have similar characteristics in terms of form, such as Heijo-kyo, the capital city of Japan during the Nara Period and Heian-kyo (today's Kyoto), the capital city of Japan during the Heian Period.

In ancient European capitals, the existing distinctive axes are mostly the result of urban transformation after the 17th century, such as the urban axis of Piazza Venezia, the Piazza del Popolo in Rome and the front of the Les Invalides in Paris.

The main driving force for their formation is the pursuit of an aesthetically pleasing urban landscape.

At the same time, in terms of landscape design, due to the influence of cultural backgrounds, they are very different from the Beijing Central Axis.

This city axis design based on landscape design also influenced the urban design of the West in the 18th, 19th, and 20th centuries, such as the capitals of Washington, Canberra and other cities.

Many medieval European cities on the World Heritage List have fundamental differences from Beijing when it comes to their formation and urban development trajectory.

Beijing was planned and constructed based on China's ideals of what a global central city should be, and the Central Axis became the core part of this ideal city form.

The medieval cities in Europe were constantly increasing and decreasing residential areas under the influence of religion, commerce, and the municipal system, and their central areas formed a complex urban texture due to this natural growth.

Moreover, some capitals in South Asia and Southeast Asia also have a central axis.

Due to cultural differences, these central axes of the capitals are mostly related to religious beliefs and local worldviews, showing a strong sacredness, such as Angkor in Cambodia, Ayutthaya in Thailand, Jaipur in India, and Yogyakarta in Indonesia.

Therefore, this difference we observe is ultimately reflected in the material form of these architectural complexes and their differences from the Beijing Central Axis.

With its irreplaceable uniqueness and prominent global value, the Beijing Central Axis fills a gap in the World Heritage List in terms of the ideals surrounding Eastern capital city planning and the types of core architectural complexes it possesses.

The author is the director of the National Heritage Center at Tsinghua University. life@globaltimes.com.cn

Illustration: Liu Xiangya/GT

It presents to the Chinese people a grand classroom for understanding the core values, history, and the spirit of traditional Chinese culture, and also provides new historical and cultural momentum for the sustainable development of the capital city.The Central Axis, located in the heart of the old city, stretches 7.8 kilometers in length north to south.

Continuously refined over more than seven centuries, it was first established in the 13th century and took shape in the 16th century, forming a holistic, orderly, and majestic urban central architectural complex.

It has witnessed the continuous evolution of the spirit of Chinese civilization in constructing the order of Chinese life and the form of the capital city.

The uniqueness of the Central Axis is reflected in the traditional Chinese philosophy and cultural spirit it embodies.

This philosophy and cultural spirit expressed through the layout and spatial form of the Central Axis has continuously determined and influenced the evolution of the entire capital city.

In addition, the axis showcases a unique architectural form and urban landscape, giving it a prominent place on the World Heritage List.

The Tian'anmen Square complex, a 20th-century architectural masterpiece, continues the traditional philosophy and planning ideas reflected in the Central Axis, demonstrating the continuity and unity of Chinese civilization.

As the most representative achievement of the mature period of Chinese capital city planning, the Central Axis gathers aspects from the core central axis designs of all Chinese dynasties.

It is the only extant example of a complete central axis architectural complex.

For example, the central axis architectural complexes in cities like Chang'an, the capital city of the Tang Dynasty (618-907), and Bianjing, the capital city of the Northern Song Dynasty (960-1127), reflect different stages of the development of the central axis of a capital city.

However, most of these cities' central axis architectural complexes have disappeared to a certain extent over time, while the Beijing Central Axi is well preserved and retains the marks of various eras.

Meanwhile, in East Asia, ancient capitals outside of China were mostly influenced by Chinese culture in terms of planning concepts and have similar characteristics in terms of form, such as Heijo-kyo, the capital city of Japan during the Nara Period and Heian-kyo (today's Kyoto), the capital city of Japan during the Heian Period.

In ancient European capitals, the existing distinctive axes are mostly the result of urban transformation after the 17th century, such as the urban axis of Piazza Venezia, the Piazza del Popolo in Rome and the front of the Les Invalides in Paris.

The main driving force for their formation is the pursuit of an aesthetically pleasing urban landscape.

At the same time, in terms of landscape design, due to the influence of cultural backgrounds, they are very different from the Beijing Central Axis.

This city axis design based on landscape design also influenced the urban design of the West in the 18th, 19th, and 20th centuries, such as the capitals of Washington, Canberra and other cities.

Many medieval European cities on the World Heritage List have fundamental differences from Beijing when it comes to their formation and urban development trajectory.

Beijing was planned and constructed based on China's ideals of what a global central city should be, and the Central Axis became the core part of this ideal city form.

The medieval cities in Europe were constantly increasing and decreasing residential areas under the influence of religion, commerce, and the municipal system, and their central areas formed a complex urban texture due to this natural growth.

Moreover, some capitals in South Asia and Southeast Asia also have a central axis.

Due to cultural differences, these central axes of the capitals are mostly related to religious beliefs and local worldviews, showing a strong sacredness, such as Angkor in Cambodia, Ayutthaya in Thailand, Jaipur in India, and Yogyakarta in Indonesia.

Therefore, this difference we observe is ultimately reflected in the material form of these architectural complexes and their differences from the Beijing Central Axis.

With its irreplaceable uniqueness and prominent global value, the Beijing Central Axis fills a gap in the World Heritage List in terms of the ideals surrounding Eastern capital city planning and the types of core architectural complexes it possesses.

The author is the director of the National Heritage Center at Tsinghua University. life@globaltimes.com.cn