ARTS / CULTURE & LEISURE

Centuries-old script of women now a social, historical bridge

Blossom under the sun

Nüshu literally means "women's writing" in Chinese, and just as its name implies, the writing system including about 500 frequently used characters has been seen as the world's only script designed and used exclusively by women. After its birth in the 19th century, the previously endangered unique script has experienced a revival, amplifying women's inner voices to the greater public.

At a recent premier event of Hidden Letters, an Oscar-shortlisted documentary centering around Nüshu, a male audience gave a standing ovation to director Feng Du and the crew as thanks for bringing the script and stories behind these words to them.

"I am touched by the film that inspires me to examine myself and listen carefully to what's inside the woman," an audience said.

The director then recalled one of the most cherished and meaningful comments about the film that she had received, from the documentary's photographer who privately messaged her to thank her for selecting him for the project as he can now better understand his daughter and grow to be a better father.

Nüshu, which was like "wild roses in the mountains," is blooming under the sun, Hu Xin, an inheritor of the script, told the Global Times.

The centuries-old script that once carried women's narratives has undergone a remarkable transformation. With a burgeoning community of artists and scholars dedicating themselves to creatively illuminating this exquisite script, it is now reaching a broader audience.

In doing so, Nüshu emerges as a potent tool for cultivating meaningful interactions between women and the society at large, as experts noted.

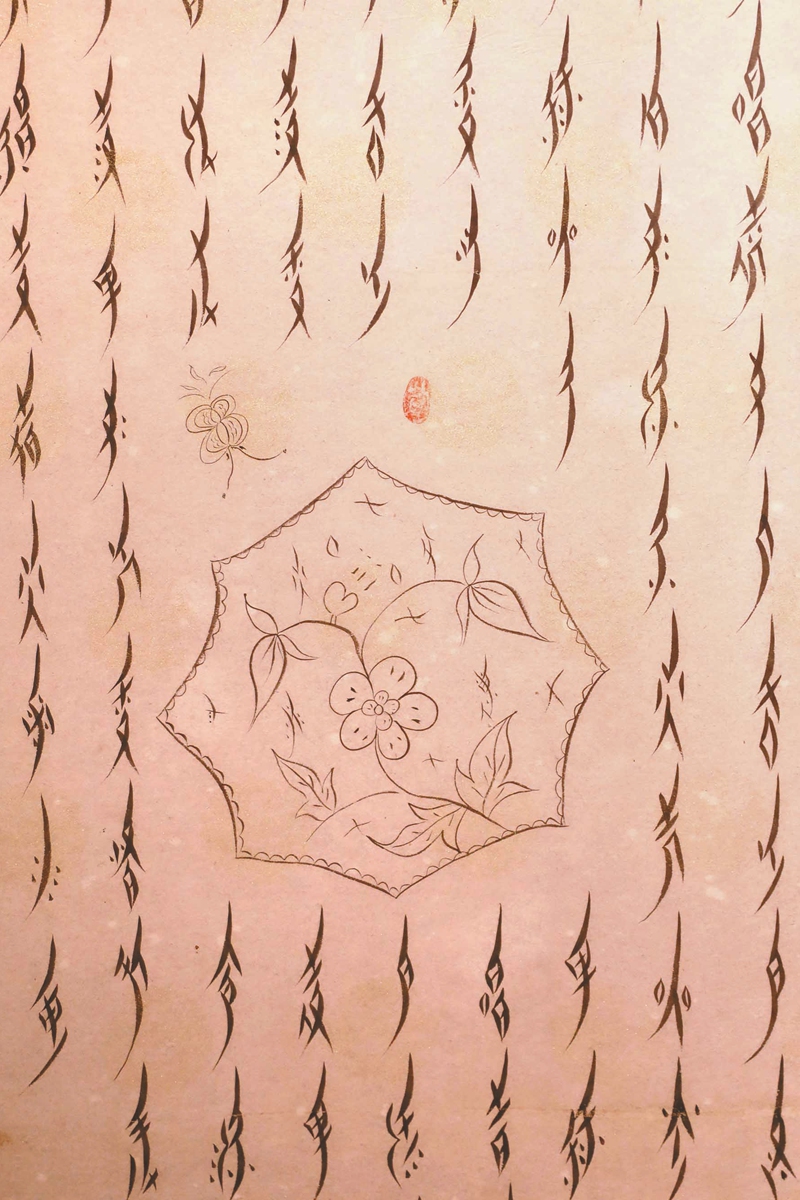

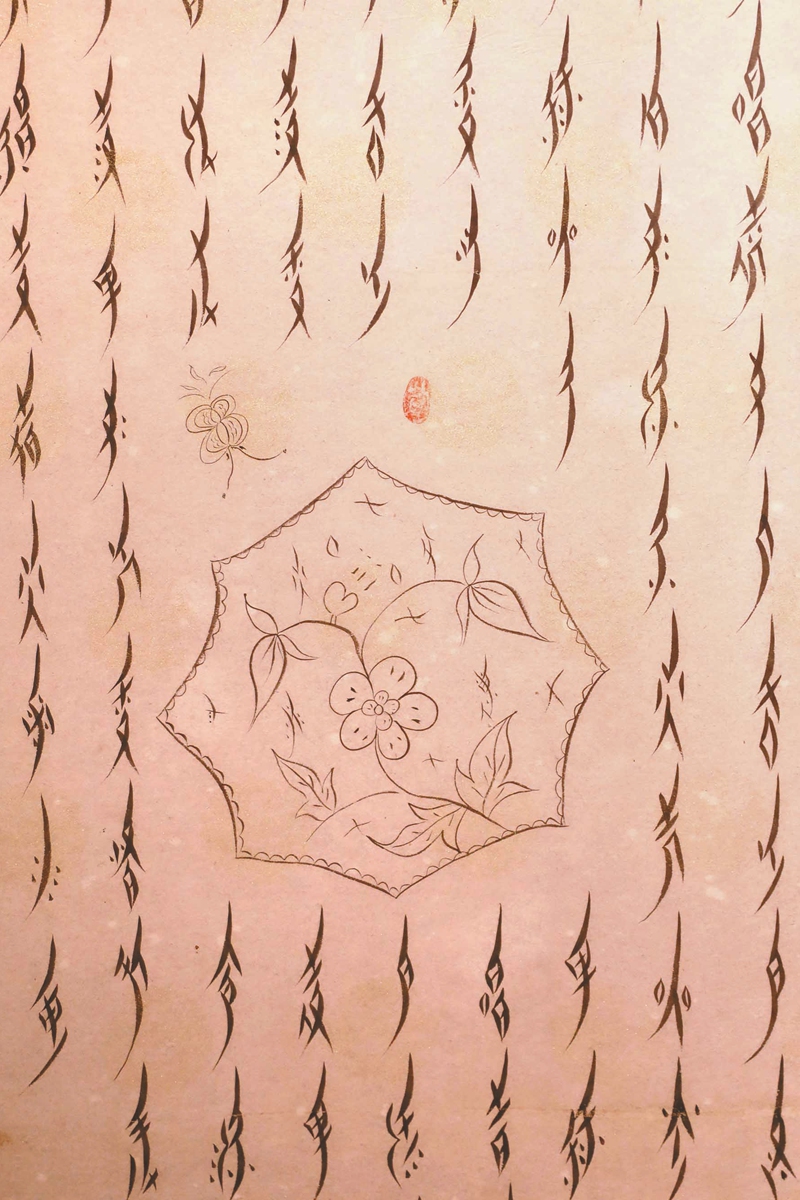

Nüshu characters, originating from Jiangyong, Central China's Hunan Province, are a rhomboid variant derived from traditional square Chinese characters. These distinct characters are composed of dots and three types of strokes: horizontals, virgules, and arcs.

The elongated letters are crafted with delicate and thread-like lines, resulting in a unique and intricate writing style.

Nüshu was primarily taught by mothers to their daughters and practiced for enjoyment among sisters and friends.

This unique script served as a means of communication for women in a feudal society, who often had limited access to formal education in reading and writing.

According to Hu, the letters and autobiographies written with Nüshu characters often recorded folk songs, riddles, and translations of ancient Chinese poems, and composed songs for rural women.

The extinction of Nüshu culture and the need to protect it have attracted particular attention since the beginning of the 21st century.

Relevant institutions such as museums and training centers were established, along with a string of diverse events for conservation and promotion, like preparing easy-to-understand manuals to explain the historical background, values, and basic elements of Nüshu, have since been launched.

Nowadays, the conservation of the script is not just being carried out by the authorities. Nüshu inheritors and buffs keep writing down what they think about life and what they strive for in the ancient script.

Si Mu, a diehard fan of Nüshu, told the Global Times that she does not consider writing Nüshu as a profession, but views the act of writing in the script as a form of relaxation and a means to connect with the historical narratives of women.

"Nüshu stands as a testament to the history of Chinese women. For me, Nüshu is a beacon of vigilance, and a constant reminder to remain spiritually independent and true to oneself," she said, adding that during her study of Nüshu, she became more confident and thought more independently when communicating with men.

The innovative integration of Nüshu into modern culture was also demonstrated during the Paris 2024 Olympics, where fans created WeChat memes written in Nüshu celebrating Chinese female athletes' achievements, including China's tennis ace Zheng Qinwen who won China's first Olympic gold medal in women's singles tennis, with phrases like "Chinese female athletes are great."

Another semester of the training class kicks off, and Hu is glad to see male students sitting in a group of women, showing their enthusiasm to learn the script.

At the museum dedicated to the preservation and research of Nüshu in Jiangyong, Hu observes an increasing number of male visitors exploring the script's recordings and introductions with curiosity. She realized that Nüshu has been able to bear the weight of dialogue between different genders and with the rest of the world after its resurgence.

Li Ailian, curator of the Nüshu Culture and Art Museum in Hunan, has also found that an increasing number of male tourists are visiting the museum.

"They [the male tourists] think Nüshu is a masterpiece of Chinese women's ancestors and has a high cultural value," said Li.

Gong Zhebing, director of the Nüshu Research Center at Wuhan University's National Institute of Cultural Development in Hubei Province was among the first to rediscover and conduct research on Nüshu.

Gong told the Global Times that he believes the script has also served as a bridge for communication between men and women.

Nüshu was inscribed on China's national intangible cultural heritage list, and in light of its growing international influence, Hu mentioned that efforts have begun to pursue recognition on the UNESCO Intangible Cultural Heritage List to further preserve the script.

Nüshu characters in the Nüshu Museum in Jiangyong County, Central China's Hunan Province Photo: IC

Following are some of the changes undergone by Nüshu over time and what the writing system has maintained.At a recent premier event of Hidden Letters, an Oscar-shortlisted documentary centering around Nüshu, a male audience gave a standing ovation to director Feng Du and the crew as thanks for bringing the script and stories behind these words to them.

"I am touched by the film that inspires me to examine myself and listen carefully to what's inside the woman," an audience said.

The director then recalled one of the most cherished and meaningful comments about the film that she had received, from the documentary's photographer who privately messaged her to thank her for selecting him for the project as he can now better understand his daughter and grow to be a better father.

Nüshu, which was like "wild roses in the mountains," is blooming under the sun, Hu Xin, an inheritor of the script, told the Global Times.

The centuries-old script that once carried women's narratives has undergone a remarkable transformation. With a burgeoning community of artists and scholars dedicating themselves to creatively illuminating this exquisite script, it is now reaching a broader audience.

In doing so, Nüshu emerges as a potent tool for cultivating meaningful interactions between women and the society at large, as experts noted.

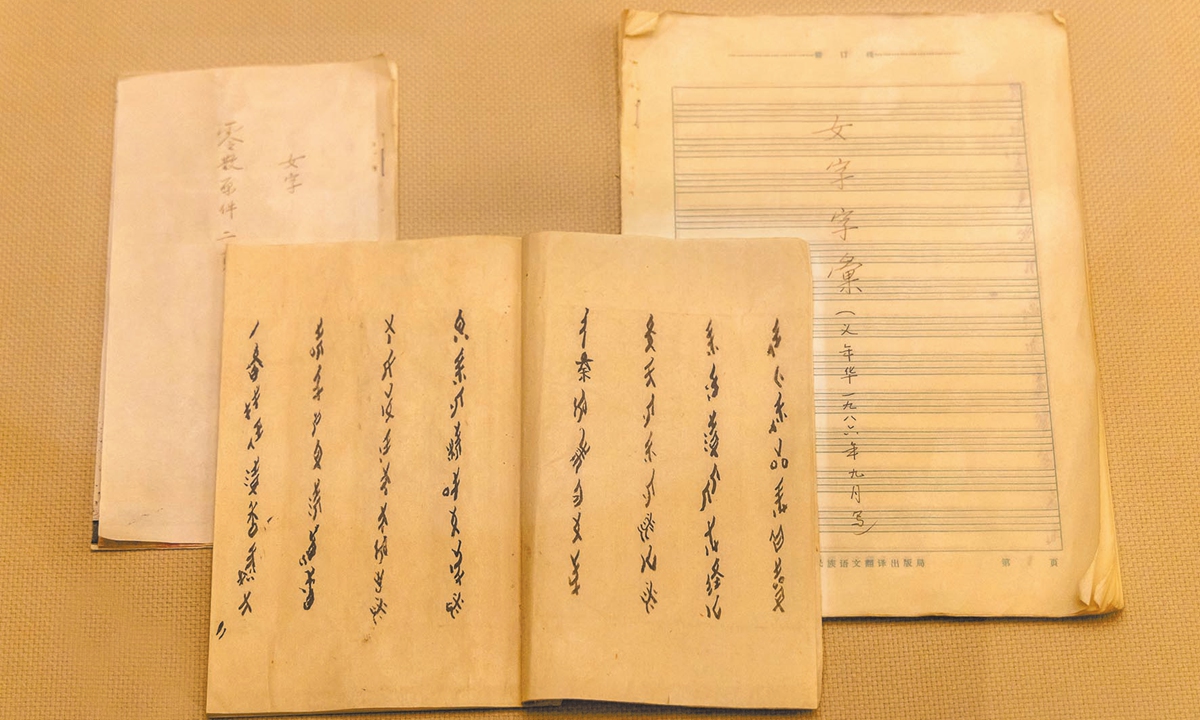

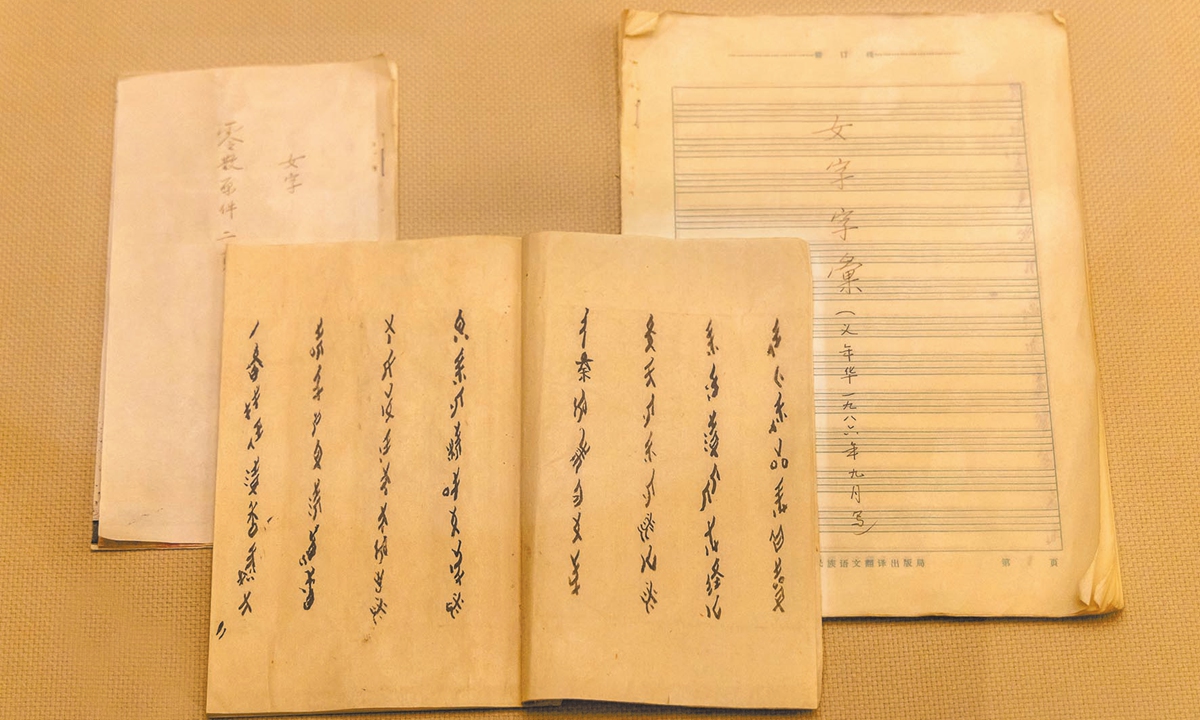

Scattered original copies of Nüshu, Nüshu letters, and handwritten Nüshu Vocabulary by Yi Nianhua, one of the last writers of Nüshu in 1988-89, are on display at China National Museum of Women and Children in Beijing. Photo: VCG

Ancient but vibrantNüshu characters, originating from Jiangyong, Central China's Hunan Province, are a rhomboid variant derived from traditional square Chinese characters. These distinct characters are composed of dots and three types of strokes: horizontals, virgules, and arcs.

The elongated letters are crafted with delicate and thread-like lines, resulting in a unique and intricate writing style.

Nüshu was primarily taught by mothers to their daughters and practiced for enjoyment among sisters and friends.

This unique script served as a means of communication for women in a feudal society, who often had limited access to formal education in reading and writing.

According to Hu, the letters and autobiographies written with Nüshu characters often recorded folk songs, riddles, and translations of ancient Chinese poems, and composed songs for rural women.

The extinction of Nüshu culture and the need to protect it have attracted particular attention since the beginning of the 21st century.

Relevant institutions such as museums and training centers were established, along with a string of diverse events for conservation and promotion, like preparing easy-to-understand manuals to explain the historical background, values, and basic elements of Nüshu, have since been launched.

Nowadays, the conservation of the script is not just being carried out by the authorities. Nüshu inheritors and buffs keep writing down what they think about life and what they strive for in the ancient script.

Si Mu, a diehard fan of Nüshu, told the Global Times that she does not consider writing Nüshu as a profession, but views the act of writing in the script as a form of relaxation and a means to connect with the historical narratives of women.

"Nüshu stands as a testament to the history of Chinese women. For me, Nüshu is a beacon of vigilance, and a constant reminder to remain spiritually independent and true to oneself," she said, adding that during her study of Nüshu, she became more confident and thought more independently when communicating with men.

The innovative integration of Nüshu into modern culture was also demonstrated during the Paris 2024 Olympics, where fans created WeChat memes written in Nüshu celebrating Chinese female athletes' achievements, including China's tennis ace Zheng Qinwen who won China's first Olympic gold medal in women's singles tennis, with phrases like "Chinese female athletes are great."

At least 350 family education experts from across China write Nüshu on lacquer fans with Chinese brushes at the National Museum of Chinese Writing in Anyang, Central China's Henan Province, on June 21, 2024. Photo: VCG

More open dialogueAnother semester of the training class kicks off, and Hu is glad to see male students sitting in a group of women, showing their enthusiasm to learn the script.

At the museum dedicated to the preservation and research of Nüshu in Jiangyong, Hu observes an increasing number of male visitors exploring the script's recordings and introductions with curiosity. She realized that Nüshu has been able to bear the weight of dialogue between different genders and with the rest of the world after its resurgence.

Li Ailian, curator of the Nüshu Culture and Art Museum in Hunan, has also found that an increasing number of male tourists are visiting the museum.

"They [the male tourists] think Nüshu is a masterpiece of Chinese women's ancestors and has a high cultural value," said Li.

Gong Zhebing, director of the Nüshu Research Center at Wuhan University's National Institute of Cultural Development in Hubei Province was among the first to rediscover and conduct research on Nüshu.

Gong told the Global Times that he believes the script has also served as a bridge for communication between men and women.

Nüshu was inscribed on China's national intangible cultural heritage list, and in light of its growing international influence, Hu mentioned that efforts have begun to pursue recognition on the UNESCO Intangible Cultural Heritage List to further preserve the script.