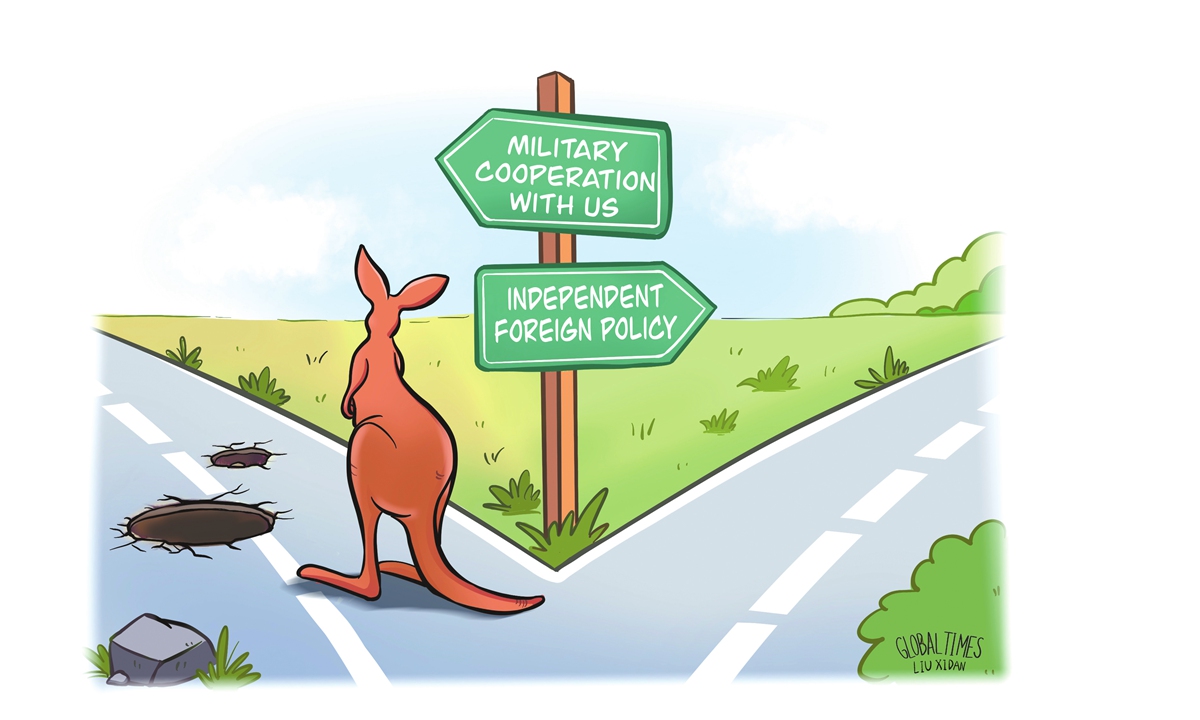

Illustration: Liu Xidan/GT

The recently concluded Australia-US Ministerial Consultations have expanded the scope and depth of cooperation between the two countries in the field of defense. The joint statement after the talks not only proposed the rotation of US maritime patrol and reconnaissance aircraft in Australia, but also regular rotations of US Army watercraft to Australia.

Although both sides have emphasized that they respect each other's sovereignty, former Australian prime minister Paul Keating's latest description of the US-Australia relationship still rings the alarm: Canberra's policy is likely to "turn Australia into the 51st state of the US."

Keating made his judgment when discussing the impact of AUKUS on Australia. He said that he believes that AUKUS was about US "military control of Australia," and Australia risks losing its autonomy. In addition to political and military risks, Australia also faces huge economic and environmental risks due to the nuclear submarine cooperation in AUKUS.

Whether it is the ceding of autonomy or the proactive assuming of a series of nuclear-related risks, the question still remains: What is Australia's intention?

Recently, the Australian think tank Institute of Public Affairs released a report outlining a blueprint for Australia's defense construction, recommending that the rotational presence of US Marine Corps rotations in northern Australia be expanded to approximately 16,000 between 2025 and 2028. This could be Australia's "cheapest boost" to deterrence, the report said. Obviously, deterring China may be a significant factor in Australia's willingness to bear such a high cost.

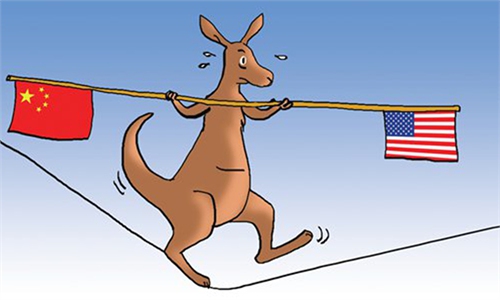

After the Albanese government came to power, it extended an olive branch to China and adopted a pragmatic policy toward the country. As a result, China-Australia relations are on the rise again after hitting rock bottom. However, against the backdrop of continuous improvement of relations with China, Australia still, to some extent, treats the country as if it were an enemy, constantly pushing the boundaries of military cooperation with its allies. It even does not hesitate to cede its autonomy and bear various risks which it could avoid. Walking on a diplomatic tightrope is not something worth bragging about for Australia.

First, Australia's military deployment with China as the imaginary enemy will seriously damage the political mutual trust between the two countries. During the Scott Morrison administration, Australia acting as an anti-China vanguard and front-runner greatly hurt bilateral relations. Canberra should learn a lesson from this. The easing of bilateral relations has been hard won. Only if Australia's China policy is consistent both internally and externally, consistent in words and deeds, and free from external interference can it prevent the relationship from deteriorating.

Second, Australia has continuously ceded its own national interests in the process of cooperation with the US, undermining its reputation as an independent foreign policy pursuer. A revamped version of the AUKUS agreement, for instance, shows that Australia has to bear a variety of risks while the US is given the unique right to effectively terminate the agreement and withdraw from it if, at any time, it believes that the AUKUS agreement would be detrimental to its interests. This is clearly not an agreement that is equal for all parties.

Australia has adopted a seemingly flexible but actually unwise foreign policy that will not fool China or the Australian people who are not willing to pay for the risks associated with AUKUS cooperation. Such a "tightrope" is not an easy route, and Australia needs to fine-tune its foreign policy so that it truly serves the interests of its people, rather than sacrificing their future for the benefit of other countries.

The author is an executive research fellow at the Center for Australia, New Zealand and South Pacific Studies, Chinese Academy of Social Sciences. opinion@globaltimes.com.cn