Illustration: Liu Rui/GT

The Monroe Doctrine of 1823 laid the early groundwork for this concept, claiming that the Americas were within the US sphere of influence and forbidding European interference. In the early 20th century, President Theodore Roosevelt's "Big Stick Policy" further reinforced US intervention in Latin America. By the mid-20th century, with the onset of the Cold War, the term "backyard" became more commonplace, symbolizing America's effort to counter the Soviet Union's influence in the region.

In recent years, US politicians have shown a growing interest in their "backyard" due to China's increasing connections with Latin American countries.

Recent news suggests that Brazilian President Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva plans to discuss a "long-term strategic partnership" with China later this year. He also mentioned that the Brazilian government is formulating a proposal to join China's Belt and Road Initiative (BRI).

Currently, there are only a few countries in South America that have not officially joined this initiative. Brazil, being the most significant country on the continent, would likely influence regional relations with China if it participated in the BRI.

This situation suggests that Latin America proactively seeks a new balance in the shifting global geopolitical landscape. In an increasingly multipolar world, Latin America needs to carve out an independent path for its development.

The US acknowledges the changes happening in its "backyard." Recently, General Laura Richardson, head of the US Southern Command responsible for defense in Latin America, suggested that the US should consider a "Marshall Plan" for the region.

Last month, Secretary of State Antony Blinken announced the launch of the Western Hemisphere Semiconductor Initiative at a ministerial meeting of the Americas Partnership for Economic Prosperity. Additionally, Treasury Secretary Janet Yellen visited Brazil during the G20 Finance Ministers and Central Bank Governors meeting. US media outlets have interpreted these developments as resonating with the intent to address China's regional influence.

However, upon examining the desires of China, the US and Latin American countries like Brazil, it becomes evident that the US efforts to reclaim the "backyard" strategy from the Cold War may not yield the desired results.

Why are China and Latin American countries like Brazil keen to strengthen cooperation? This collaboration aligns with the developmental strategies of both parties.

The complementarity of the Brazil-China economy has long been recognized as irreplaceable. There are international concerns that Brazil relies too heavily on exports of raw materials such as iron ore, oil and soybeans to China. Yet, recent investments by China in Brazilian manufacturing and active participation in energy and telecommunications infrastructure projects have addressed these worries. These sectors are also vital for Brazil's development and, in the long run, could facilitate Brazil's economic transformation.

As the US remains the most important economic and trade partner for major Latin American nations like Brazil, if the country were genuinely willing to help Latin America develop through a new "Marshall Plan," Latin American countries would certainly welcome it.

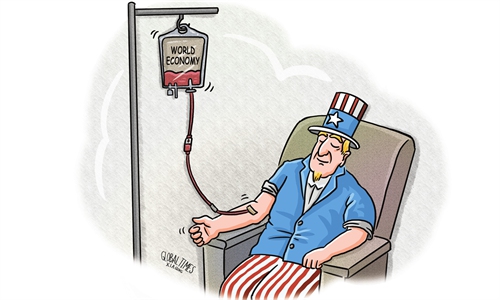

Since the US aggressively promoted the "Washington Consensus" in the 1990s without any significant success, it has primarily neglected investment in Latin American manufacturing and infrastructure, only paying attention when China entered what they considered their "backyard."

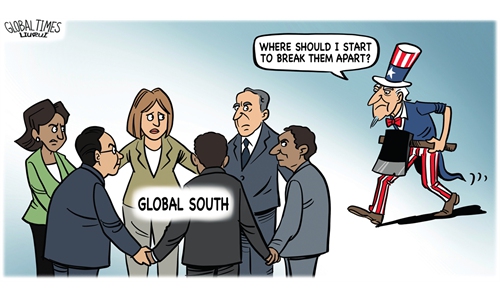

Washington's strategic moves, in response to China's presence in the region, do not aim to foster win-win cooperation but rather to counter China.

The intention is not to engage in collaboration but to diminish China's influence and push it out of the region. This dynamic compels Latin American countries to choose sides and adds political and economic pressure on them.

On a broader global scale, the US' zero-sum approach is increasingly provoking backlash, leading more countries to seek to balance US strategic pressure by enhancing cooperation with China.

However, a salient characteristic of hegemony is that it does not emerge alongside participants but asserts a dominant "aura." Washington's dilemma is whether or not it should use the resources it has to push China out of the region and maintain its status as the "leader" in Latin America over the long term.