Illustration: Liu Rui/GT

This summer, I embarked on a journey to Baoji, a city in Northwest China's Shaanxi Province steeped in China's ancient history.Like countless other visitors, my primary destination was the Baoji Bronze Ware Museum, home to a treasure trove of artifacts from China's Bronze Age.

One artifact stood out above all others: the He Zun, a bronze wine vessel that holds immense historical and linguistic significance.

The He Zun, dating back to the early Western Zhou Dynasty (circa 1046BC-771BC), bears the earliest known inscription of zhongguo, the two Chinese characters for the English word "China." The phrase zhaizi zhongguo, meaning "dwelling in this central land," is etched into its surface, a testament to the longevity of Chinese civilization.

When a Westerner who has never been to China thinks of China, what's the first thing that comes to mind? Maybe, an ancient Eastern nation known for its porcelain, a powerful entity regarded by the US as a rival or even an enemy, or a nation led by a communist party that differs from Western civilization and ideology. If this is what they think of first, they are clearly unaware of the meaning behind zhongguo and what it represents.

In the ancient context from He Zun, "China" referred not to a nation-state as we understand it today, but to a central geographical area. Specifically, it indicated the region surrounding present-day Luoyang in Henan Province, which was considered the heart of the Zhou polity. This nuance is crucial for understanding the evolution of Chinese identity over millennia.

It's important to emphasize that this early usage primarily denotes a geographical concept rather than a national or ethnic one. The focus was on determining the location for the central seat of government, not on defining a nation in the modern sense.

This stands in stark contrast to the formation of European states, which often coalesced around ethnic and linguistic groups, frequently intertwined with religious identities. These divergent origins have profoundly influenced how these civilizations conceptualize statehood and nationhood to this day.

The notion of China as the "Middle Kingdom" has long held sway in Western understanding, often oversimplifying China's complex historical self-perception.

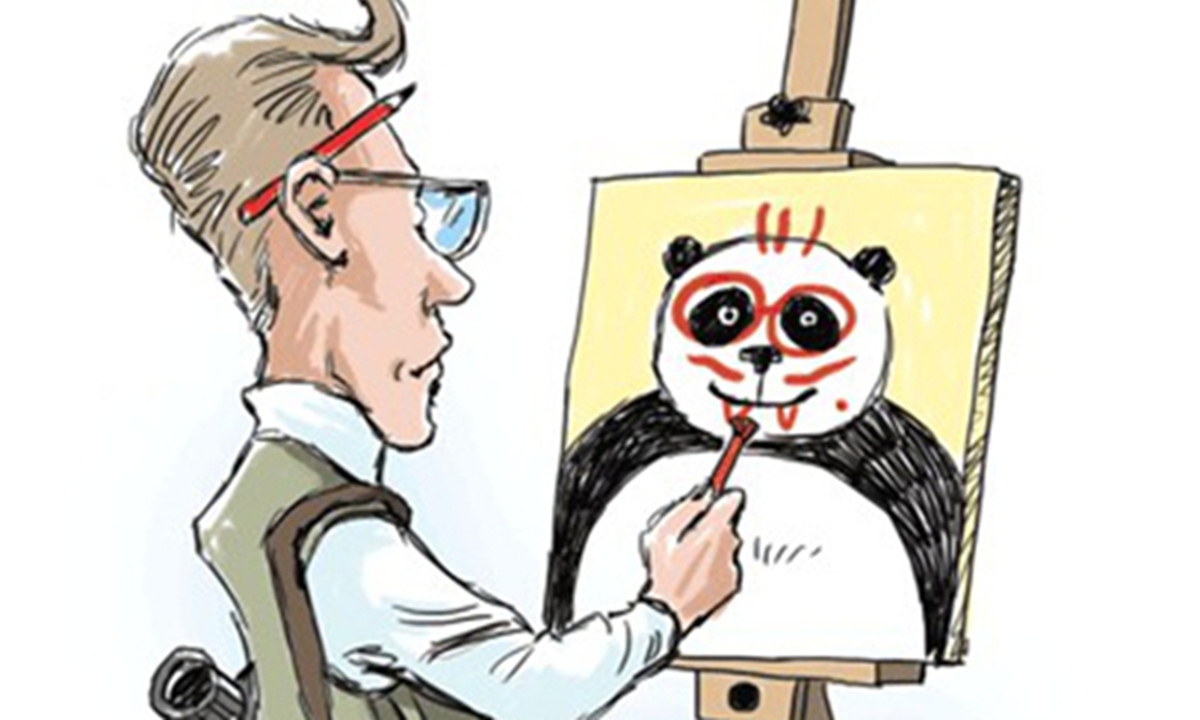

This oversimplification has inadvertently created a linguistic trap, suggesting that China's very emergence was driven by an inherent, imperialistic desire to unify tianxia, or "all under heaven," a concept that has been frequently misinterpreted in Western discourse.

My colleague, Wang Wen, Executive Dean of the Chongyang Institute for Financial Studies at Renmin University of China, provides valuable insight into this issue. In his thought-provoking article "Is the name 'China' full of imperialist overtones?" Wang traces the roots of this misunderstanding. He argues that since the publication of Samuel Wells Williams' influential book The Middle Kingdom in 1883, the global understanding of China has been heavily influenced by Western academia's narrative of "China equals the Middle Kingdom," portraying it as a nationalistic empire.

Wang contends that it is problematic to perpetuate this historical interpretation in analyzing China's contemporary rise. It risks fabricating a false narrative of China seeking to unify the world under its rule, inadvertently lending credence to alarmist theories of a "China threat" or "Chinese hegemony."

Such misinterpretations can have serious implications for international relations and global stability.

Understanding China through the origin of its name is not merely an academic exercise; it's crucial for accurately conveying China's story to the world. The narrative surrounding the etymology of zhongguo reflects a critical choice: should we reexamine China from the roots of its civilization, or continue to operate within the traditional Western cognitive framework?

At its core, this is a question of how to deconstruct outdated perceptions and establish more accurate ones. This process of reevaluation directly impacts our ability to comprehensively and accurately understand Chinese modernization, a concept that has a long historical and cultural background which has gained prominence in recent years.

The author is a senior editor with the People's Daily, and currently a senior fellow with the Chongyang Institute for Financial Studies at the Renmin University of China. dinggang@globaltimes.com.cn. Follow him on X @dinggangchina