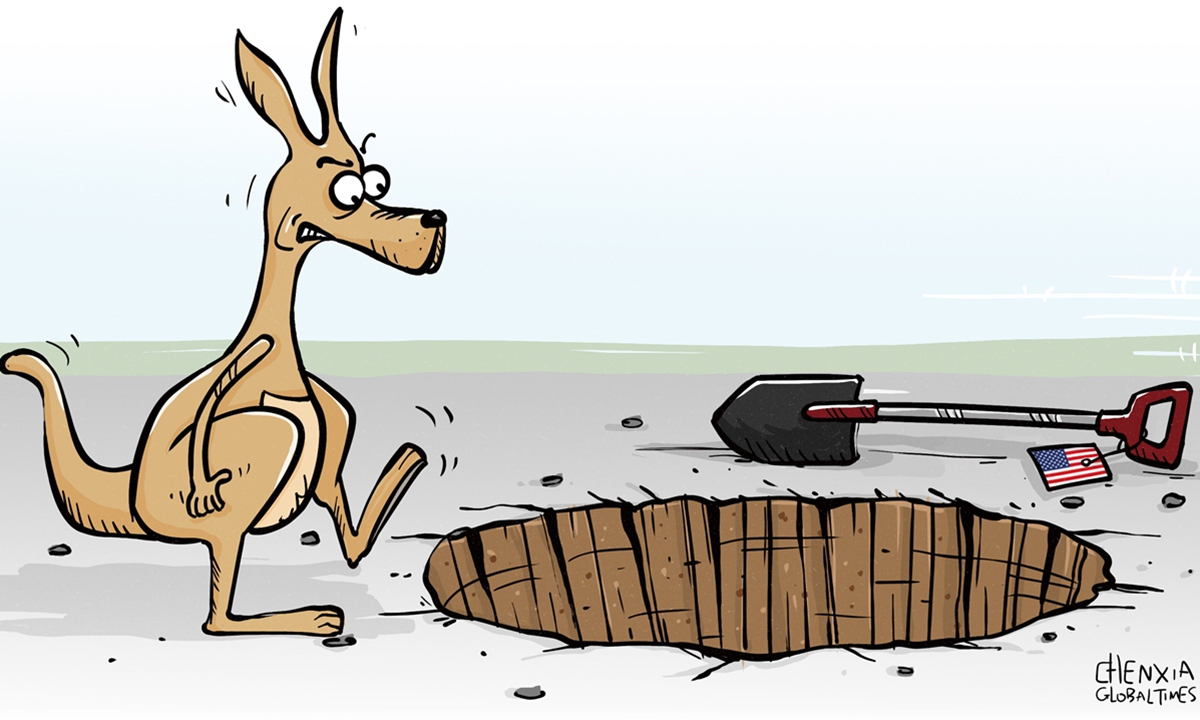

Illustration: Chen Xia/GT

The refreshed AUKUS agreement, following the latest Australia-US Ministerial Consultations (AUSMIN), is facing a growing cascade of critical reactions from prominent Australians in the world of politics and public policy. Former prime minister Paul Keating was among the first to voice his concerns. With his usual poise, he put the question of national sovereignty fairly onto the public agenda.Keating argued that AUKUS would effectively turn Australia into the "51st state" of America. He was echoed by former foreign minister Gareth Evans, former Australian ambassador to Beijing Ross Garnaut, emeritus professor Hugh White of the Australian National University and others, forming a chorus of critics speaking out against the agreement.

At heart, the issue is the acquiescence of Australian sovereignty to American interests, wherein Australian national security has been exposed to greater risk. America may see China as a threat. However, no one in Australia has explicitly argued, let alone persuasively demonstrated, that China poses or has the means to be a material threat to Australia. Fear works best when the imagination can fill voids.

The US seeks to recover Asian primacy. The rationale of AUKUS' submarine proposition is fundamentally tied to this strategic ambition. Whether the submarines are American or Australian is actually immaterial to the Americans; certainly, as has been observed by various Congressional Research Office assessments, if providing new submarines to Australia compromises American requirements, then there will be no new submarines to Australia.

Right now, the US produces an average of 1.3 submarines annually. To meet AUKUS requirements without compromising American needs, this production rate has to increase to 2.4 submarines per year. This task is easier said than done. At best, Australian ports will have the privilege of hosting American submarines. A legal requirement for providing submarines to Australia is that the US president at the time must sign off that American requirements will not be compromised. That Australia has no recourse or "claw back" in these conditions is part of the "operational critique" of the refreshed AUKUS arrangements.

These operational deficiencies are, however, overshadowed by the issues of the evolving realities in Asia itself. China's modernized military is now more than a match for the Americans. Put plainly, unbridled American military preponderance in Asia is a thing of the past. This is unlikely to change in the foreseeable future. This makes the AUKUS gambit, from Australia's point of view, something of a "fool's errand" at the expense of national sovereignty and security.

Only a subimperial reflex conflates the American pursuit of primacy with Australia's national security interest.

But, if the recovery of American primacy is a fantasy, what are the other possibilities? White argues that the other possibilities boil down to either ASEAN primacy in which the US maintains a presence in Asia, not as a hegemonic power but as a "balancing power," or a future in which the US retreats from Asia altogether. These are the realistic possibilities, rather than ideological and nostalgic-driven fantasies of American primacy 2.0.

For now, despite the growing levels of critical reaction, the security establishment is doubling down. The issues that have been raised by White and other critics have generally been ignored or dismissed as "outdated" or "out of touch." Parallel discussions in the less "cut and thrust" world of academic research have also echoed many of these concerns. That said, the growing number of critics, who bring a certain amount of expert or political heft, cannot be ignored forever.

The Australian government (first Morrison and subsequently Albanese) jumped into the AUKUS arrangements without any substantial public ventilation. Morrison's abandonment of the previous contract with the French for conventional submarines in favor of AUKUS was, according to Andrew Fowler in his recent book Nuked: The Submarine Fiasco that Sank Australia's Sovereignty, made at the behest of those in Washington who were increasingly alarmed that Australia was forging security arrangements that would mute the potential influence of the US over Australian policy priorities.

But resistance to this subordination is emerging and growing. The chorus of critical voices occasioned by the recent extension of the AUKUS arrangements at AUSMIN suggests that while the subimperial reflex is the default reaction among the policy establishment, it isn't the only viewpoint in Australia on questions of national security and sovereignty.

There is likely to be a long way to run yet on this set of fundamental issues. The debate is only beginning to heat up, and will continue to slow burn as Australians are again confronted with a core question of their country's identity, both historically and into the future. With Asia emerging as a power center in its own right, and as American preponderance fades in the rearview mirror, a policy that defaults to the pursuit of US primacy in Asia is unlikely to be sustainable.

No doubt, Washington will have a view on this too - which uncomfortably and inconveniently reinforces the concerns about forfeiture of sovereignty that is increasingly seen to be intrinsic to the DNA of AUKUS.

The author is chairman at Smart Trade Networks, adjunct professor at the Queensland University of Technology and former policy advisor to Kevin Rudd. opinion@globaltimes.com.cn