IN-DEPTH / IN-DEPTH

Bloody history: Japanese army slaughtered more than 100,000 Filipino civilians in desperate revenge in Manila Massacre

Japanese army slaughtered more than 100,000 Filipino civilians in desperate revenge in Manila Massacre

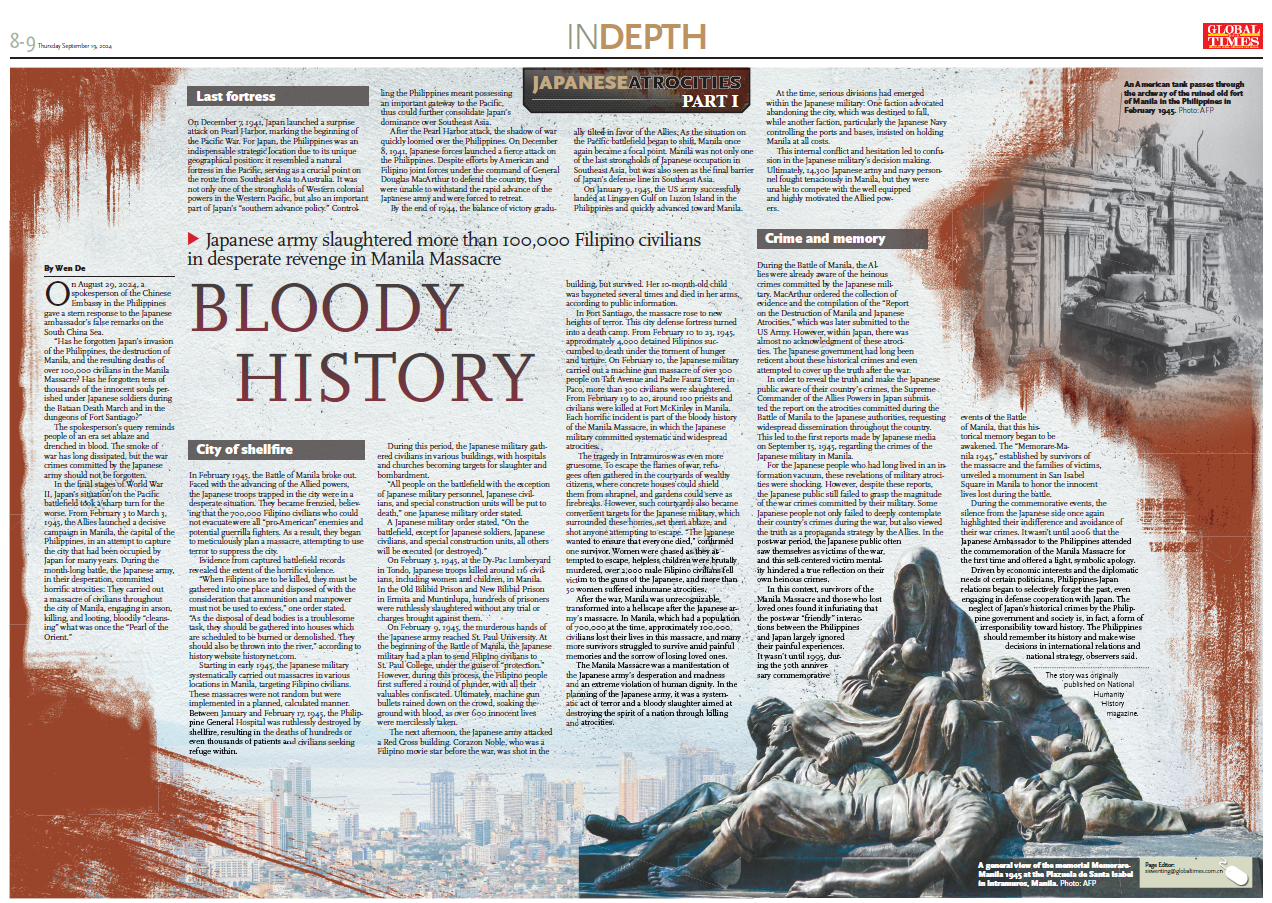

A general view of the memorial Memorare-Manila 1945 at the Plazuela de Santa Isabel in Intramuros, Manila. Photo: AFP

On August 29, 2024, a spokesperson of the Chinese Embassy in the Philippines gave a stern response to the Japanese ambassador's false remarks on the South China Sea."Has he forgotten Japan's invasion of the Philippines, the destruction of Manila, and the resulting deaths of over 100,000 civilians in the Manila Massacre? Has he forgotten tens of thousands of the innocent souls perished under Japanese soldiers during the Bataan Death March and in the dungeons of Fort Santiago?"

The spokesperson's query reminds people of an era set ablaze and drenched in blood. The smoke of war has long dissipated, but the war crimes committed by the Japanese army should not be forgotten.

In the final stages of World War II, Japan's situation on the Pacific battlefield took a sharp turn for the worse. From February 3 to March 3, 1945, the Allies launched a decisive campaign in Manila, the capital of the Philippines, in an attempt to capture the city that had been occupied by Japan for many years. During the month-long battle, the Japanese army, in their desperation, committed horrific atrocities: They carried out a massacre of civilians throughout the city of Manila, engaging in arson, killing, and looting, bloodily "cleansing" what was once the "Pearl of the Orient."

Last fortress

On December 7, 1941, Japan launched a surprise attack on Pearl Harbor, marking the beginning of the Pacific War. For Japan, the Philippines was an indispensable strategic location due to its unique geographical position: it resembled a natural fortress in the Pacific, serving as a crucial point on the route from Southeast Asia to Australia. It was not only one of the strongholds of Western colonial powers in the Western Pacific, but also an important part of Japan's "southern advance policy." Controlling the Philippines meant possessing an important gateway to the Pacific, thus could further consolidate Japan's dominance over Southeast Asia.

After the Pearl Harbor attack, the shadow of war quickly loomed over the Philippines. On December 8, 1941, Japanese forces launched a fierce attack on the Philippines. Despite efforts by American and Filipino joint forces under the command of General Douglas MacArthur to defend the country, they were unable to withstand the rapid advance of the Japanese army and were forced to retreat.

By the end of 1944, the balance of victory gradually tilted in favor of the Allies. As the situation on the Pacific battlefield began to shift, Manila once again became a focal point. Manila was not only one of the last strongholds of Japanese occupation in Southeast Asia, but was also seen as the final barrier of Japan's defense line in Southeast Asia.

On January 9, 1945, the US army successfully landed at Lingayen Gulf on Luzon Island in the Philippines and quickly advanced toward Manila.

At the time, serious divisions had emerged within the Japanese military: One faction advocated abandoning the city, which was destined to fall, while another faction, particularly the Japanese Navy controlling the ports and bases, insisted on holding Manila at all costs.

This internal conflict and hesitation led to confusion in the Japanese military's decision making. Ultimately, 14,300 Japanese army and navy personnel fought tenaciously in Manila, but they were unable to compete with the well equipped and highly motivated the Allied powers.

An American tank passes through the archway of the ruined old fort of Manila in the Philippines in February 1945. Photo: AFP

City of shellfireIn February 1945, the Battle of Manila broke out. Faced with the advancing of the Allied powers, the Japanese troops trapped in the city were in a desperate situation. They became frenzied, believing that the 700,000 Filipino civilians who could not evacuate were all "pro-American" enemies and potential guerrilla fighters. As a result, they began to meticulously plan a massacre, attempting to use terror to suppress the city.

Evidence from captured battlefield records revealed the extent of the horrific violence.

"When Filipinos are to be killed, they must be gathered into one place and disposed of with the consideration that ammunition and manpower must not be used to excess," one order stated. "As the disposal of dead bodies is a troublesome task, they should be gathered into houses which are scheduled to be burned or demolished. They should also be thrown into the river," according to history website historynet.com.

Starting in early 1945, the Japanese military systematically carried out massacres in various locations in Manila, targeting Filipino civilians. These massacres were not random but were implemented in a planned, calculated manner. Between January and February 17, 1945, the Philippine General Hospital was ruthlessly destroyed by shellfire, resulting in the deaths of hundreds or even thousands of patients and civilians seeking refuge within.

During this period, the Japanese military gathered civilians in various buildings, with hospitals and churches becoming targets for slaughter and bombardment.

"All people on the battlefield with the exception of Japanese military personnel, Japanese civilians, and special construction units will be put to death," one Japanese military order stated.

A Japanese military order stated, "On the battlefield, except for Japanese soldiers, Japanese civilians, and special construction units, all others will be executed (or destroyed)."

On February 3, 1945, at the Dy-Pac Lumberyard in Tondo, Japanese troops killed around 116 civilians, including women and children, in Manila. In the Old Bilibid Prison and New Bilibid Prison in Ermita and Muntinlupa, hundreds of prisoners were ruthlessly slaughtered without any trial or charges brought against them.

On February 9, 1945, the murderous hands of the Japanese army reached St. Paul University. At the beginning of the Battle of Manila, the Japanese military had a plan to send Filipino civilians to St. Paul College, under the guise of "protection." However, during this process, the Filipino people first suffered a round of plunder, with all their valuables confiscated. Ultimately, machine gun bullets rained down on the crowd, soaking the ground with blood, as over 600 innocent lives were mercilessly taken.

The next afternoon, the Japanese army attacked a Red Cross building. Corazon Noble, who was a Filipino movie star before the war, was shot in the building, but survived. Her 10-month-old child was bayoneted several times and died in her arms, according to public information.

In Fort Santiago, the massacre rose to new heights of terror. This city defense fortress turned into a death camp. From February 10 to 23, 1945, approximately 4,000 detained Filipinos succumbed to death under the torment of hunger and torture. On February 10, the Japanese military carried out a machine gun massacre of over 300 people on Taft Avenue and Padre Faura Street; in Paco, more than 300 civilians were slaughtered. From February 19 to 20, around 100 priests and civilians were killed at Fort McKinley in Manila. Each horrific incident is part of the bloody history of the Manila Massacre, in which the Japanese military committed systematic and widespread atrocities.

The tragedy in Intramuros was even more gruesome. To escape the flames of war, refugees often gathered in the courtyards of wealthy citizens, where concrete houses could shield them from shrapnel, and gardens could serve as firebreaks. However, such courtyards also became convenient targets for the Japanese military, which surrounded these homes, set them ablaze, and shot anyone attempting to escape. "The Japanese wanted to ensure that everyone died," confirmed one survivor. Women were chased as they attempted to escape, helpless children were brutally murdered, over 2,000 male Filipino civilians fell victim to the guns of the Japanese, and more than 50 women suffered inhumane atrocities.

After the war, Manila was unrecognizable, transformed into a hellscape after the Japanese army's massacre. In Manila, which had a population of 700,000 at the time, approximately 100,000 civilians lost their lives in this massacre, and many more survivors struggled to survive amid painful memories and the sorrow of losing loved ones.

The Manila Massacre was a manifestation of the Japanese army's desperation and madness and an extreme violation of human dignity. In the planning of the Japanese army, it was a systematic act of terror and a bloody slaughter aimed at destroying the spirit of a nation through killing and atrocities.

Crime and memory

During the Battle of Manila, the Allies were already aware of the heinous crimes committed by the Japanese military. MacArthur ordered the collection of evidence and the compilation of the "Report on the Destruction of Manila and Japanese Atrocities," which was later submitted to the US Army. However, within Japan, there was almost no acknowledgment of these atrocities. The Japanese government had long been reticent about these historical crimes and even attempted to cover up the truth after the war.

In order to reveal the truth and make the Japanese public aware of their country's crimes, the Supreme Commander of the Allies Powers in Japan submitted the report on the atrocities committed during the Battle of Manila to the Japanese authorities, requesting widespread dissemination throughout the country. This led to the first reports made by Japanese media on September 15, 1945, regarding the crimes of the Japanese military in Manila.

For the Japanese people who had long lived in an information vacuum, these revelations of military atrocities were shocking. However, despite these reports, the Japanese public still failed to grasp the magnitude of the war crimes committed by their military. Some Japanese people not only failed to deeply contemplate their country's crimes during the war, but also viewed the truth as a propaganda strategy by the Allies. In the post-war period, the Japanese public often saw themselves as victims of the war, and this self-centered victim mentality hindered a true reflection on their own heinous crimes.

In this context, survivors of the Manila Massacre and those who lost loved ones found it infuriating that the post-war "friendly" interactions between the Philippines and Japan largely ignored their painful experiences. It wasn't until 1995, during the 50th anniversary commemorative events of the Battle of Manila, that this historical memory began to be awakened. The "Memorare-Manila 1945," established by survivors of the massacre and the families of victims, unveiled a monument in San Isabel Square in Manila to honor the innocent lives lost during the battle.

During the commemorative events, the silence from the Japanese side once again highlighted their indifference and avoidance of their war crimes. It wasn't until 2006 that the Japanese Ambassador to the Philippines attended the commemoration of the Manila Massacre for the first time and offered a light, symbolic apology.

Driven by economic interests and the diplomatic needs of certain politicians, Philippines-Japan relations began to selectively forget the past, even engaging in defense cooperation with Japan. The neglect of Japan's historical crimes by the Philippine government and society is, in fact, a form of irresponsibility toward history. The Philippines should remember its history and make wise decisions in international relations and national strategy, observers said.

The story was originally published on National Humanity History magazine.