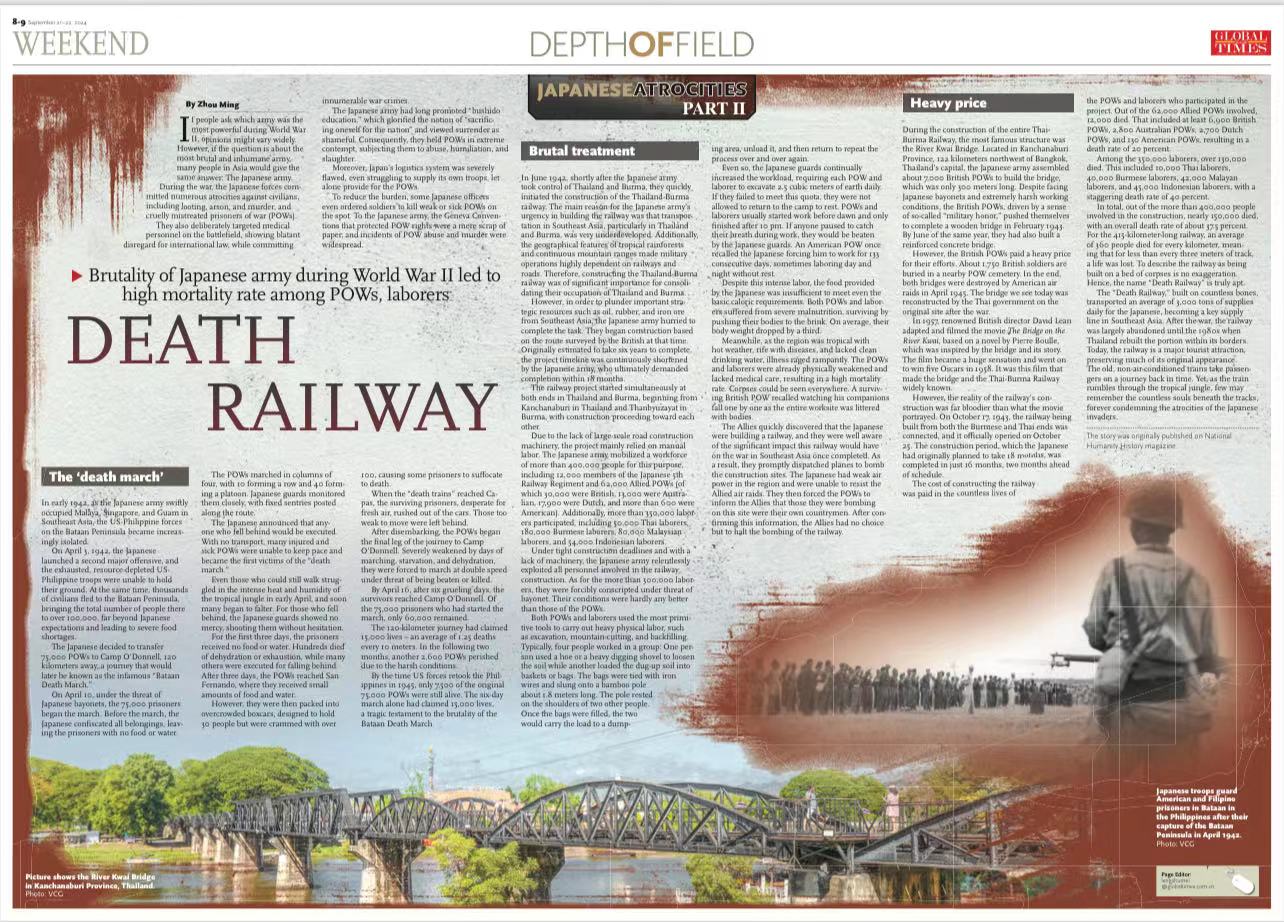

Japanese troops guard American and Filipino prisoners in Bataan in the Philippines after their capture of the Bataan Peninsula in April 1942. Photo: VCG

If people ask which army was the most powerful during World War II, opinions might vary widely. However, if the question is about the most brutal and inhumane army, many people in Asia would give the same answer: The Japanese army.

During the war, the Japanese forces committed numerous atrocities against civilians, including looting, arson, and murder, and cruelly mistreated prisoners of war (POWs).

They also deliberately targeted medical personnel on the battlefield, showing blatant disregard for international law, while committing innumerable war crimes.

The Japanese army had long promoted "bushido education," which glorified the notion of "sacrificing oneself for the nation" and viewed surrender as shameful. Consequently, they held POWs in extreme contempt, subjecting them to abuse, humiliation, and slaughter.

Moreover, Japan's logistics system was severely flawed, even struggling to supply its own troops, let alone provide for the POWs.

To reduce the burden, some Japanese officers even ordered soldiers to kill weak or sick POWs on the spot. To the Japanese army, the Geneva Conventions that protected POW rights were a mere scrap of paper, and incidents of POW abuse and murder were widespread.

The 'death march'In early 1942, as the Japanese army swiftly occupied Malaya, Singapore, and Guam in Southeast Asia, the US-Philippine forces on the Bataan Peninsula became increasingly isolated.

On April 3, 1942, the Japanese launched a second major offensive, and the exhausted, resource-depleted US-Philippine troops were unable to hold their ground. At the same time, thousands of civilians fled to the Bataan Peninsula, bringing the total number of people there to over 100,000, far beyond Japanese expectations and leading to severe food shortages.

The Japanese decided to transfer 75,000 POWs to Camp O'Donnell, 120 kilometers away, a journey that would later be known as the infamous "Bataan Death March."

On April 10, under the threat of Japanese bayonets, the 75,000 prisoners began the march. Before the march, the Japanese confiscated all belongings, leaving the prisoners with no food or water.

The POWs marched in columns of four, with 10 forming a row and 40 forming a platoon. Japanese guards monitored them closely, with fixed sentries posted along the route.

The Japanese announced that anyone who fell behind would be executed. With no transport, many injured and sick POWs were unable to keep pace and became the first victims of the "death march."

Even those who could still walk struggled in the intense heat and humidity of the tropical jungle in early April, and soon many began to falter. For those who fell behind, the Japanese guards showed no mercy, shooting them without hesitation.

For the first three days, the prisoners received no food or water. Hundreds died of dehydration or exhaustion, while many others were executed for falling behind. After three days, the POWs reached San Fernando, where they received small amounts of food and water.

However, they were then packed into overcrowded boxcars, designed to hold 30 people but were crammed with over 100, causing some prisoners to suffocate to death.

When the "death trains" reached Capas, the surviving prisoners, desperate for fresh air, rushed out of the cars. Those too weak to move were left behind.

After disembarking, the POWs began the final leg of the journey to Camp O'Donnell. Severely weakened by days of marching, starvation, and dehydration, they were forced to march at double speed under threat of being beaten or killed.

By April 16, after six grueling days, the survivors reached Camp O'Donnell. Of the 75,000 prisoners who had started the march, only 60,000 remained.

The 120-kilometer journey had claimed 15,000 lives - an average of 1.25 deaths every 10 meters. In the following two months, another 2,600 POWs perished due to the harsh conditions.

By the time US forces retook the Philippines in 1945, only 7,500 of the original 75,000 POWs were still alive. The six-day march alone had claimed 15,000 lives, a tragic testament to the brutality of the Bataan Death March.

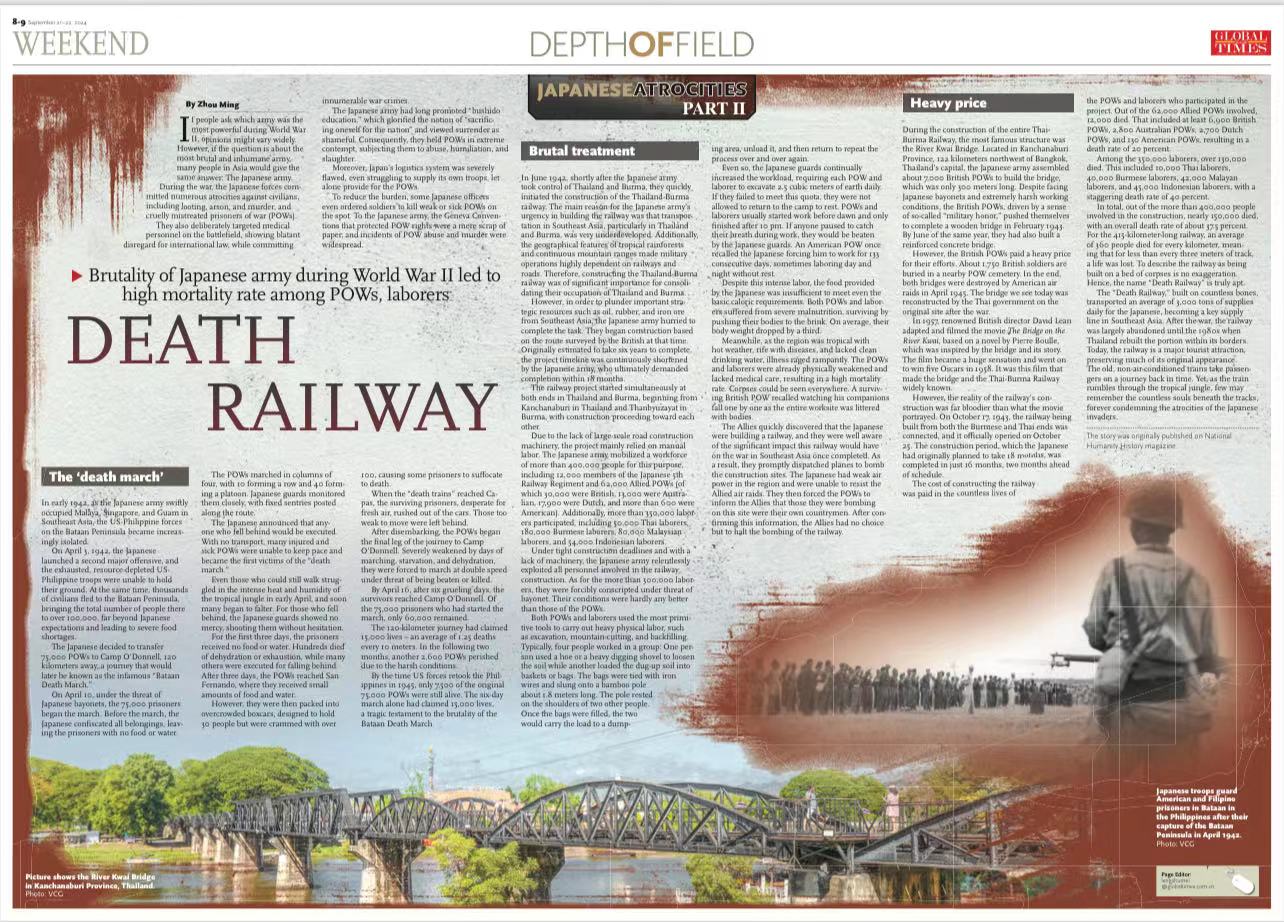

The River Kwai Bridge in Kanchanaburi Province, Thailand. Photo: VCG

Brutal treatment

In June 1942, shortly after the Japanese army took control of Thailand and Burma, they quickly initiated the construction of the Thailand-Burma railway. The main reason for the Japanese army's urgency in building the railway was that transportation in Southeast Asia, particularly in Thailand and Burma, was very underdeveloped. Additionally, the geographical features of tropical rainforests and continuous mountain ranges made military operations highly dependent on railways and roads. Therefore, constructing the Thailand-Burma railway was of significant importance for consolidating their occupation of Thailand and Burma.

However, in order to plunder important strategic resources such as oil, rubber, and iron ore from Southeast Asia, the Japanese army hurried to complete the task. They began construction based on the route surveyed by the British at that time. Originally estimated to take six years to complete, the project timeline was continuously shortened by the Japanese army, who ultimately demanded completion within 18 months.

The railway project started simultaneously at both ends in Thailand and Burma, beginning from Kanchanaburi in Thailand and Thanbyuzayat in Burma, with construction proceeding toward each other.

Due to the lack of large-scale road construction machinery, the project mainly relied on manual labor. The Japanese army mobilized a workforce of more than 400,000 people for this purpose, including 12,000 members of the Japanese 5th Railway Regiment and 62,000 Allied POWs (of which 30,000 were British, 13,000 were Australian, 17,900 were Dutch, and more than 600 were American). Additionally, more than 350,000 laborers participated, including 50,000 Thai laborers, 180,000 Burmese laborers, 80,000 Malaysian laborers, and 54,000 Indonesian laborers.

Under tight construction deadlines and with a lack of machinery, the Japanese army relentlessly exploited all personnel involved in the railway construction. As for the more than 300,000 laborers, they were forcibly conscripted under threat of bayonet. Their conditions were hardly any better than those of the POWs.

Both POWs and laborers used the most primitive tools to carry out heavy physical labor, such as excavation, mountain-cutting, and backfilling. Typically, four people worked in a group: One person used a hoe or a heavy digging shovel to loosen the soil while another loaded the dug-up soil into baskets or bags. The bags were tied with iron wires and slung onto a bamboo pole about 1.8 meters long. The pole rested on the shoulders of two other people. Once the bags were filled, the two would carry the load to a dumping area, unload it, and then return to repeat the process over and over again.

Even so, the Japanese guards continually increased the workload, requiring each POW and laborer to excavate 2.5 cubic meters of earth daily. If they failed to meet this quota, they were not allowed to return to the camp to rest. POWs and laborers usually started work before dawn and only finished after 10 pm. If anyone paused to catch their breath during work, they would be beaten by the Japanese guards. An American POW once recalled the Japanese forcing him to work for 133 consecutive days, sometimes laboring day and night without rest.

Despite this intense labor, the food provided by the Japanese was insufficient to meet even the basic caloric requirements. Both POWs and laborers suffered from severe malnutrition, surviving by pushing their bodies to the brink. On average, their body weight dropped by a third.

Meanwhile, as the region was tropical with hot weather, rife with diseases, and lacked clean drinking water, illness raged rampantly. The POWs and laborers were already physically weakened and lacked medical care, resulting in a high mortality rate. Corpses could be seen everywhere. A surviving British POW recalled watching his companions fall one by one as the entire worksite was littered with bodies.

The Allies quickly discovered that the Japanese were building a railway, and they were well aware of the significant impact this railway would have on the war in Southeast Asia once completed. As a result, they promptly dispatched planes to bomb the construction sites. The Japanese had weak air power in the region and were unable to resist the Allied air raids. They then forced the POWs to inform the Allies that those they were bombing on this site were their own countrymen. After confirming this information, the Allies had no choice but to halt the bombing of the railway.

Heavy price

During the construction of the entire Thai-Burma Railway, the most famous structure was the River Kwai Bridge. Located in Kanchanaburi Province, 122 kilometers northwest of Bangkok, Thailand's capital, the Japanese army assembled about 7,000 British POWs to build the bridge, which was only 300 meters long. Despite facing Japanese bayonets and extremely harsh working conditions, the British POWs, driven by a sense of so-called "military honor," pushed themselves to complete a wooden bridge in February 1943. By June of the same year, they had also built a reinforced concrete bridge.

However, the British POWs paid a heavy price for their efforts. About 1,750 British soldiers are buried in a nearby POW cemetery. In the end, both bridges were destroyed by American air raids in April 1945. The bridge we see today was reconstructed by the Thai government on the original site after the war.

In 1957, renowned British director David Lean adapted and filmed the movie The Bridge on the River Kwai, based on a novel by Pierre Boulle, which was inspired by the bridge and its story. The film became a huge sensation and went on to win five Oscars in 1958. It was this film that made the bridge and the Thai-Burma Railway widely known.

However, the reality of the railway's construction was far bloodier than what the movie portrayed. On October 17, 1943, the railway being built from both the Burmese and Thai ends was connected, and it officially opened on October 25. The construction period, which the Japanese had originally planned to take 18 months, was completed in just 16 months, two months ahead of schedule.

The cost of constructing the railway was paid in the countless lives of the POWs and laborers who participated in the project. Out of the 62,000 Allied POWs involved, 12,000 died. That included at least 6,900 British POWs, 2,800 Australian POWs, 2,700 Dutch POWs, and 130 American POWs, resulting in a death rate of 20 percent.

Among the 350,000 laborers, over 130,000 died. This included 10,000 Thai laborers, 40,000 Burmese laborers, 42,000 Malayan laborers, and 45,000 Indonesian laborers, with a staggering death rate of 40 percent.

In total, out of the more than 400,000 people involved in the construction, nearly 150,000 died, with an overall death rate of about 37.5 percent. For the 415-kilometer-long railway, an average of 360 people died for every kilometer, meaning that for less than every three meters of track, a life was lost. To describe the railway as being built on a bed of corpses is no exaggeration. Hence, the name "Death Railway" is truly apt.

The "Death Railway," built on countless bones, transported an average of 3,000 tons of supplies daily for the Japanese, becoming a key supply line in Southeast Asia. After the war, the railway was largely abandoned until the 1980s when Thailand rebuilt the portion within its borders. Today, the railway is a major tourist attraction, preserving much of its original appearance. The old, non-air-conditioned trains take passengers on a journey back in time. Yet, as the train rumbles through the tropical jungle, few may remember the countless souls beneath the tracks, forever condemning the atrocities of the Japanese invaders.

The story was originally published on National Humanity History magazine.

Death railway