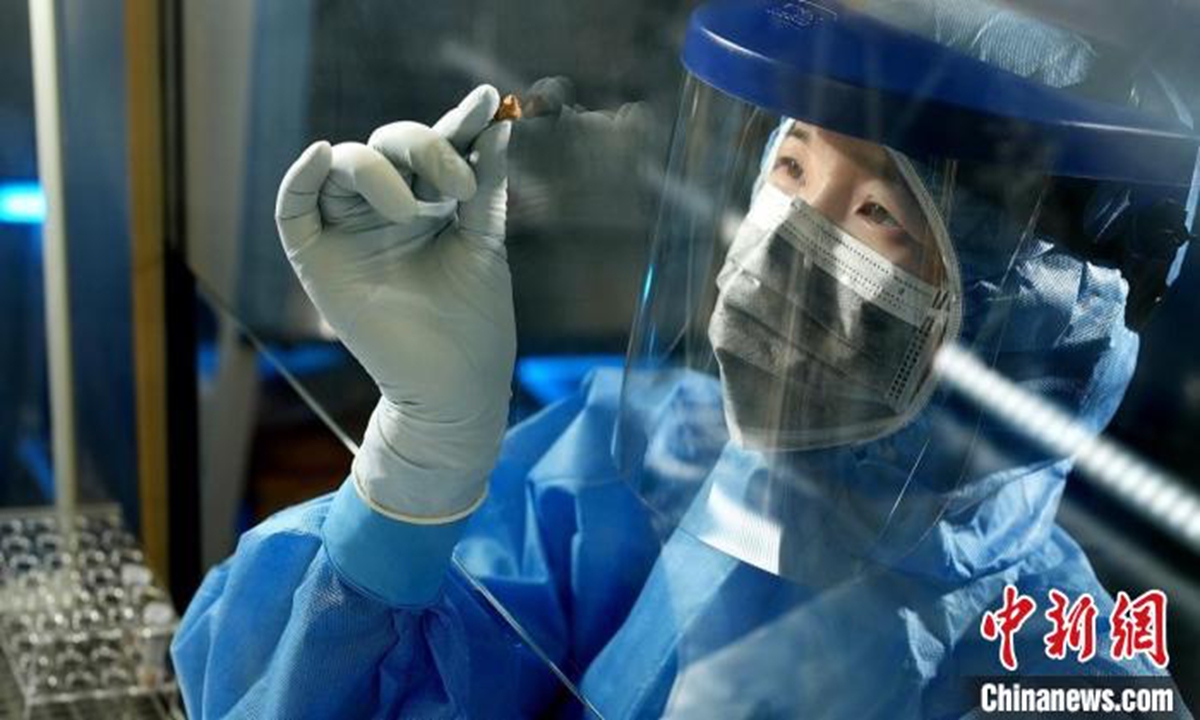

Fu Qiaomei, a researcher from the Institute of Vertebrate Paleontology and Paleoanthropology of the Chinese Academy of Sciences, conducts experiments on cheese samples in a clean room. Photo: Screenshot from China News Service

Chinese scientists have developed ancient DNA technology to systematically study the microbial genomes of the "oldest cheese," which was discovered from the Bronze Age at the Xiaohe cemetery in Northwest China's Xinjiang Uygur Autonomous Region. This research reveals two routes for the diffusion of cheese fermentation techniques in the prehistoric Tarim Basin, shedding light on the lifestyle and cultural exchanges of ancient populations in the region, according to China News Service.

Fu Qiaomei, a researcher from the Institute of Vertebrate Paleontology and Paleoanthropology of the Chinese Academy of Sciences, led the research, which was published as a highly recommended paper in the journal Cell on Wednesday.

The research team designed probes for the complete genome of Lactobacillus, raising the DNA concentration of lactic acid bacteria in the kefir cheese samples from around 0.43 percent to 0.55 percent, to 64 percent to 80 percent, making it the first successful case of ancient whole-genome research.

The cheese samples, identified as kefir through earlier ancient protein studies, date back approximately 3,500 years. They were made using kefir grains, which ferment milk into a distinctive yogurt.

By reconstructing the microbial communities involved in the fermentation process, researchers confirmed that the kefir cheese was produced by using lactic acid bacteria, with evidence suggesting that the goats used for milk production originated from a lineage that spread across Eurasia after the Neolithic period. This suggests a probable connection between ancient populations in the Tarim Basin and groups in the Eurasian steppe during that time.

The study also identified a previously unknown route for the dissemination of kefir bacteria. It found the lactic acid bacteria used for fermentation split into two main branches: One associated with strains from Europe and coastal regions of Asia, and the other linked to strains found in inland East Asia, including Southwest China's Xizang Autonomous Region. This indicates that kefir production techniques likely spread from Xinjiang to other parts of East Asia through cultural exchanges.

Researchers believe this differentiation in kefir bacteria strains reflects how ancient populations adapted and shared fermentation practices. By comparing ancient and modern kefir bacteria genomes, the team explored the evolution of these microbes over thousands of years, revealing significant adaptations to environmental pressures and interactions with humans.

This research underscores the long-standing relationship between humans and microorganisms, highlighting the critical role of fermented foods in our dietary history. It provides new insights into how ancient peoples applied and adapted fermentation techniques, contributing to our understanding of cultural exchanges and human development over time.

Global Times