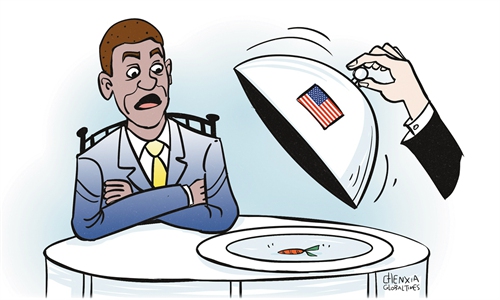

Illustration: Chen Xia/GT

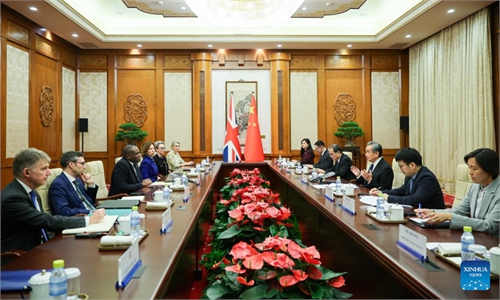

After more than a decade of the UK neglecting Africa, the country's Foreign Secretary David Lammy recently concluded his maiden tour of Africa to reconnect with the continent. His visit to Nigeria and South Africa during the first week of November 2024 lifted the veil on how the Western country perceives the continent.

Lammy was keen to talk about economic growth as the core mission of the UK government and its relations with Nigeria and South Africa, and also climate matters. Many are skeptical about how much success Britain can expect to have in establishing long-term and mutually beneficial relationships with African nations. For one, the issue of Britain's colonial history in Africa looms larger now more than ever.

During the last 20 years of the 19th century alone, Britain occupied or annexed 13 countries which accounted for more than 30 percent of Africa's population. Cruel and heinous acts were committed such as brutal murders and vicious beatings for which African's are yet to receive an apology and reparation justice.

Thousands of documents detailing some of the vicious acts were systematically destroyed to prevent post independent governments from using them in pursuit of justice.

When the Commonwealth Heads of Government Meeting (CHOGM) met at the end of October, just a few days before Lammy's visit to Africa, the UK government downplayed the British problem in Africa. This will have significant implications and will, without a doubt, derail relations.

CHOGM is made up of 56 nations, of which 19 are from the African continent. CHOGM had taken the position that it was time for the UK to make amends in the form of an apology and reparatory justice for the colonial period. But the UK stated, in no uncertain terms, that it would not apologize or make amends for the atrocious crimes that the country committed in Africa during the colonial period.

These were startling remarks as images of women and children penned like cattle for the slave trade, and men chained like wild animals and villages burnt have never been far from Africa's collective memory. The UK may intend to take on its new journey to re-engage with Africa, but will soon find out that Africa has no appetite for diplomatic platitudes.

In what seemed like a frail attempt to soften the blow, while touring Africa, Lammy stated reparation justice could take different forms and that Britain is prepared to benefit developing nations with the transfer of Britain scientific and technical expertise.

Against this backdrop of a painful, dark history and Britain's new ambitious plans for Africa, one may doubt if Britain's strength can match its ambitions in Africa. It has its own growing and pressing challenges at home, where the cost of living has skyrocketed and homelessness is a top concern.

The population in Africa has quadrupled between 1960 and 2020 to nearly 1.5 billion. UK-Africa trade relations declined from 2012 onwards and yet measures to rectify the decline were not taken until now. There are those who perceive Britain as having abandoned Africa at its time of need.

Having been taken its precious gems and artifacts, Africa had nothing more to offer Britain. Compared to leaders from other large economies, British prime ministers have rarely visited Africa nor attended the regular EU-Africa summits, which are attended by other European leaders.

The continent has suffered significant political neglect from the UK. It has been abandoned as a problematic and hungry-for-aid region, with 54 nations and more than a billion people being left behind amid many pressing development challenges.

On people-to-people contact, the rejection rate for African visitors to the UK is running at double the rate of that of any other region. This will impede Britain's influence on the continent as it hinders educational exchange and cultural connections.

The UK foreign secretary was talking about a "new approach" in relations with Africa, and the UK now wants to hear "what our African partners need and foster relationships so that the UK and our friends and partners in Africa can grow together." This in itself is a problematic statement and reveals that the UK is not alive to the new Africa. The African continent has been speaking for decades that it has no appetite for diplomatic platitudes.

The author is a Kenya-based journalist. opinion@globaltimes.com.cn