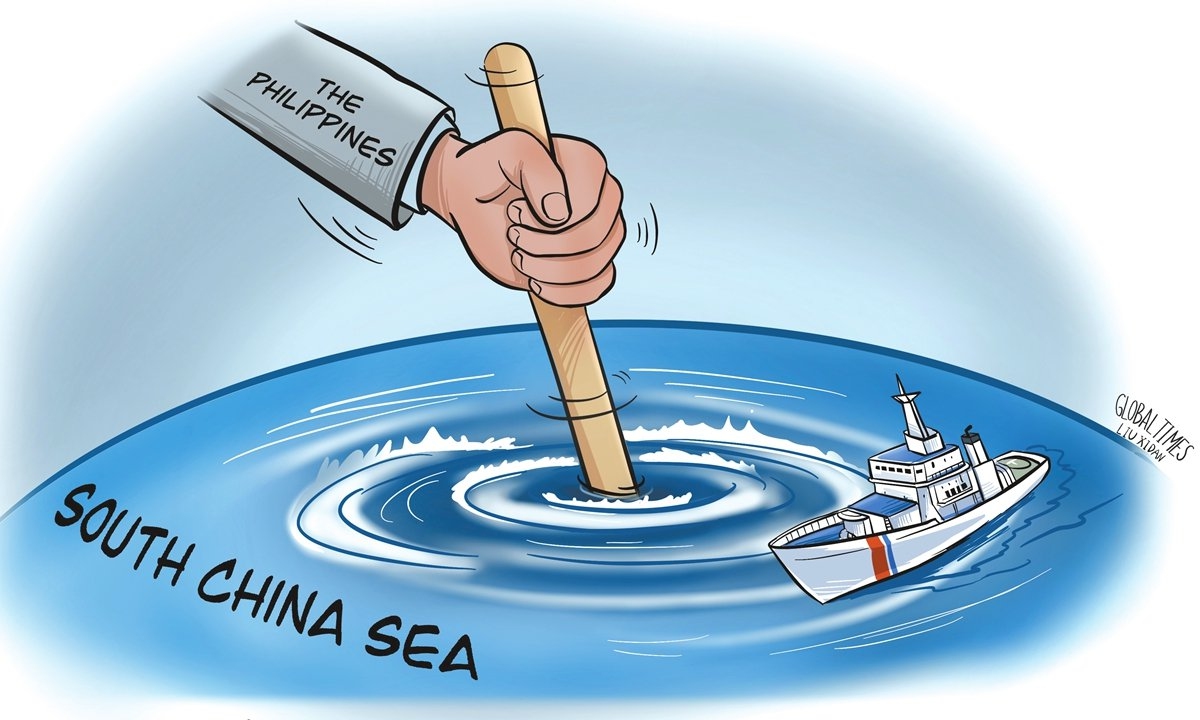

Illustration: Liu Xidan/GT

Recently, Manila has been stepping up its provocations in the South China Sea. Last Friday, the Philippines introduced two domestic laws - the Philippine Marine Zones (PMZ) Act and the Philippine Archipelagic Sea Lanes (PASL) Act - in an attempt to solidify the illegal South China Sea Arbitration Award in domestic legislation. Since November 4, the Philippines has been conducting combat drills, which include simulations of "seizing islands in the disputed waters in the South China Sea." The Philippines' Defense Secretary recently told The Financial Times that the country is considering purchasing mid-range missile launchers from the US.

The timing of such intense provocations raises doubts about Manila's motives. In particular, the introduction of the PMZ Act and the PASL Act has led to analysis suggesting that Manila intends to "legalize" its infringement activities through domestic laws, thereby creating "facts on the ground" to pressure the next US administration into continuing its support. Manila is so intoxicated with this dangerous path that it no longer even realizes it, even rushing to offer itself as a pawn. Not surprisingly, the US State Department immediately expressed support for the Philippines' domestic legislation, with Washington promptly handing over the gasoline just as Manila creates a fireball.

The two "acts" introduced by the Philippines resemble "pirate laws" in the South China Sea. The world not only fails to sense any goodwill from Manila toward peace but instead feels as if it has entered "plunder mode." These laws not only attempt to legitimize the illegal South China Sea arbitration case but also aim to impose sovereign management over sea lanes in areas that do not belong to it, linking navigation rights with the South China Sea disputes and restricting the legitimate passage of other countries' ships and aircraft. This violates the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea and goes against several International Maritime Organization resolutions. In provoking and intensifying regional tensions, it also lays the groundwork for possible future external military intervention in regional affairs.

This so-called domestic legislation is essentially an adoption of Washington's tactic of disrupting regional stability under the guise of international law, mirroring the Philippines' other acts of infringement and provocation in the South China Sea over the past two years. In response to this deliberate attempt to stoke regional tensions, on November 10, the Chinese government announced the baselines of the territorial sea adjacent to Huangyan Dao, highlighting to the international community the Philippines' malicious infringement of China's sovereignty in South China Sea. This is also intended to strengthen marine management with clearer rules and take countermeasures in the future, providing other relevant parties with expectations for action.

China issued the Law of the People's Republic of China on the Territorial Sea and the Contiguous Zone as early as 1992. This means that China has long been able, in accordance with the UN Convention on the Law of the Sea and its own law, to delineate and announce the baseline for Huangyan Dao. The fact that it had not been officially announced until now reflects China's goodwill toward neighboring countries in handling maritime issues. However, this does not mean that China will abandon the protection of its own rights, nor does it mean that it will tolerate Manila to recklessly disrupt peace in the South China Sea.

One thing is certain: each step of Manila's provocation will be met by further Chinese measures to protect its rights and counteract. The path of provocation leads only to self-harm; Manila cannot expect to gain any advantage, nor should it entertain the illusion that provocations can serve as an "guarantee slip" for itself. Moreover, Manila should recognize that its collusion with the US is turning the South China Sea into a volatile and dangerous zone, going against the long-standing consensus and expectations of regional countries. It is positioning itself as a disruptor, a destabilizer, and a culprit in undermining regional peace and stability.

Manila's provocations, incited by Washington, go completely against the wishes of the people in the region. Surveys indicate that most people in ASEAN countries believe that the best solution for the South China Sea issue is negotiation between the parties involved or setting aside disputes and pursuing joint development. This represents a valuable experience and unique wisdom for resolving South China Sea issues among regional countries. The common wishes of regional countries are for peace rather than conflict, solidarity rather than division, and development rather than poverty.

What Manila needs most now is to calm down and not rely on a few supportive statements from Western media as "moral support," nor fantasize about having an army behind it. If it truly cares about its national interests, the best course for Manila would be to halt provocations, return to dialogue and negotiations with China to resolve disputes, and cooperate with regional countries to promote substantial progress in negotiating the Code of Conduct in the South China Sea.