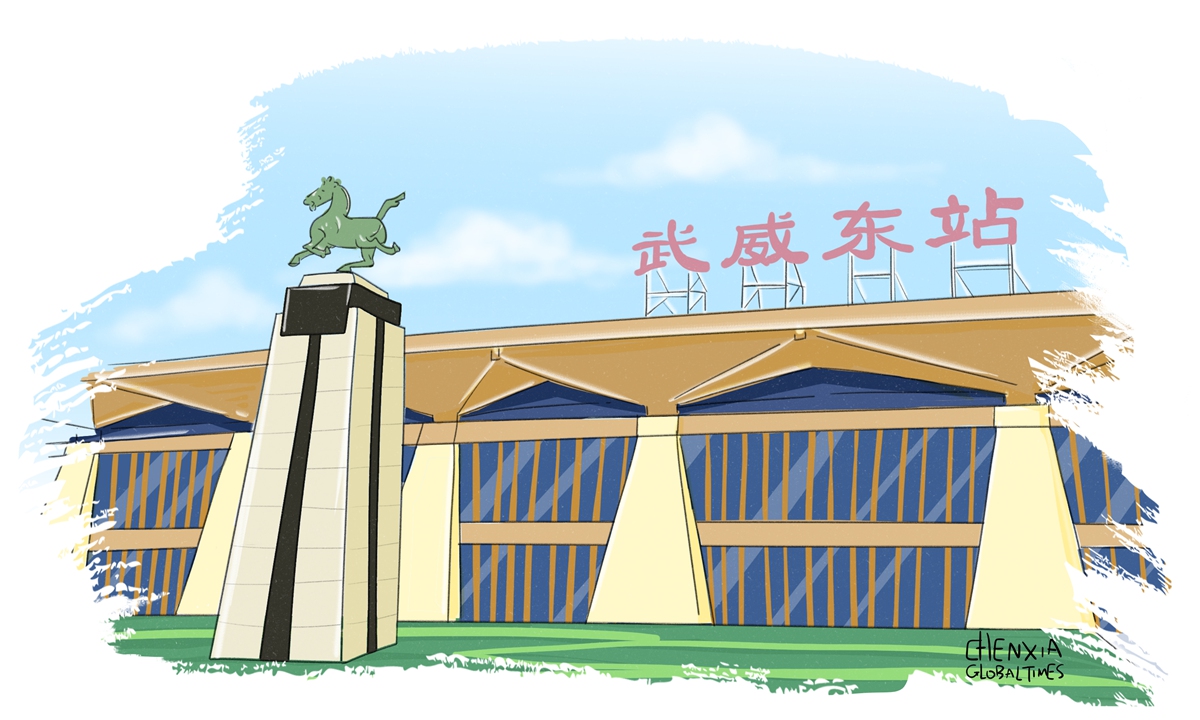

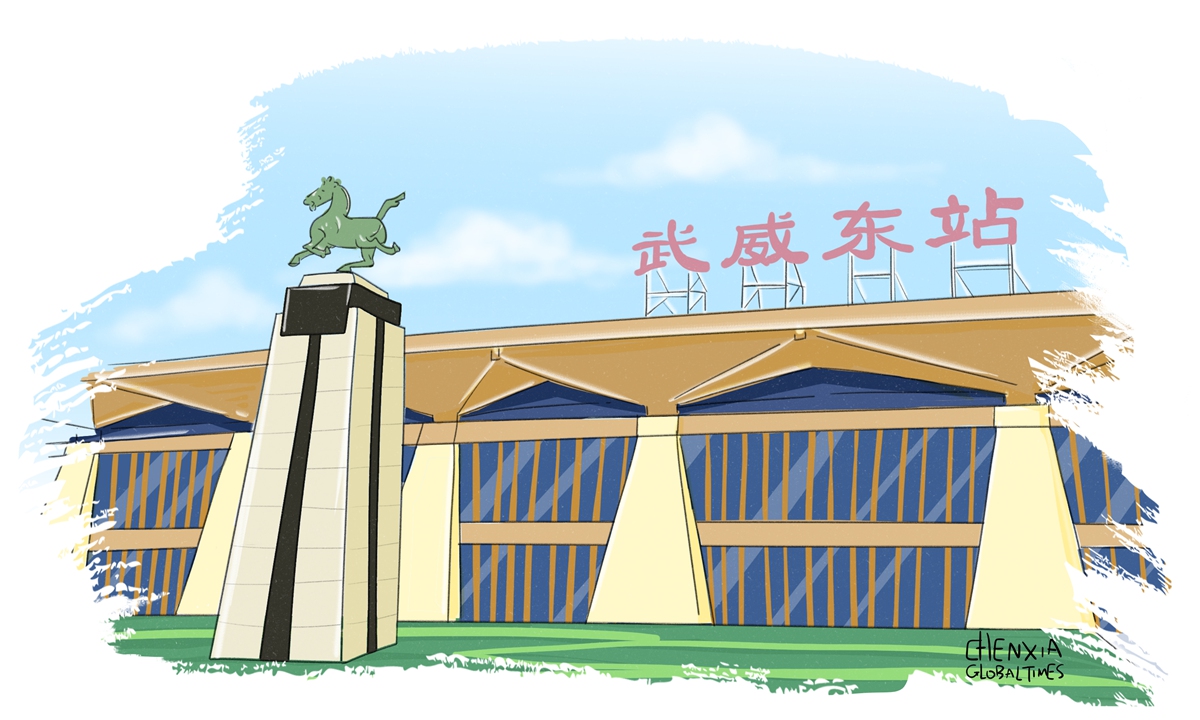

Illustratioon: Chen Xia/GT

Among the 800 or so railway stations in China, the stations in Wuwei, Gansu Province, and Chengdu in Sichuan Province have recently become internet sensations. These sites are neither the busiest nor the largest transportation hubs, so what have people found so intriguing? It seems that the story of "XL-sized cultural relics" is the answer to that question.

Take the Chengdu East Railway Station for example. The site looks nothing like a standard station, but rather a museum with cultural relics displayed outdoors. Two enlarged replicas of Neolithic Age bronze mask have become part of supporting pillars for the station's main building.

Not only have cultural relics become part of the architecture, but they have also been chosen as major decorations in public landscapes.

For example, an XL-sized replica of an Eastern Han (25-220) bronze horse now stands in front of the Wuwei East Railway Station.

Excavated in the city in 1969, the original artifact is a national-level treasure that is better known as the "Galloping Horse Treading on a Flying Swallow."

If people can visit museums to see the original artifacts, why bother putting these replicas in public spaces? The key to understand this tactic is to take a look at how Chinese cities have been implementing strategic cultural tourism plans.

The Chengdu East Railway Station's bronze masks are not some random artifact, but icons that represent the Sanxingdui Ruins, a more than 4,000-year-old site that is located in the city.

The mask is a stellar archaeological relic on display at the local museum, but by installing it in a public space, the bronze relic and Sanxingdui's heritage become symbols highlighting the city's cultural assets.

In other words, an artifact in a public landscape speaks for the city, telling visitors its cultural "personality" that they cannot find anywhere else.

These installations are like appetizers prepared for visitors before starting their urban cultural feast. This also might be the reason why such designs are commonly seen at railway stations, the first stop for many visitors.

On lifestyle sharing platform Little Red Book, or Xiaohongshu, one netizen shared an interesting story. After viewing the bronze horse sculpture at Wuwei East Railway Station, she was curious to see "the original work at the Gansu Provincial Museum."

This means of expanding the presence of such installations seems to be working, bringing in more visitors to museums and creating a ripple effect that has ignited a museum craze.

Whether they are secured inside a museum or showcased in public plazas, what makes relics become "must see" items are their power to inspire the public's curiosity about China's diverse historical culture.

Other than railway stations in Wuwei and Chengdu, other stations in cities such as Anyang and Fuyang also display their own legacies.

Inside the station in Anyang, Central China's Henan Province, oracle bone scripts from the city's Yinxu Ruins are being used to add flavor to the decor.

Meanwhile, the Hangzhou West Railway Station boasts 800 relics that were all unearthed from the site before the construction of the station.

Such a maneuver has made the station, which is known for its smart technological designs, a rare example that also has an archaeological exhibition hall.

While displaying replicas in public spaces is a creative concept, the accuracy of these replicas has to be carefully monitored.

The first thing to watch out for are poorly designed replicas that could mislead the public. The second is including appropriate introductions to the original artifacts that can help bring Chinese culture into people's everyday lives.

In the future, this trend may be further developed into more futuristic forms following the popularizing of artificial intelligence (AI) and virtual digital tools. In Nanchang, an "AI digital man" has already been employed as a tour guide providing immersive explanations to young people about Chinese porcelain culture.

In another example, by incorporating augmented reality interactive devices, the public can scan these displays with their mobile devices to learn the historical context behind them, transforming passive viewing into active exploration.

Additionally, regular cultural events can also be held in public spaces that have such XL-sized sculptures. Such events aim to deepen people's interest in learning about Chinese cultural heritage.

There are multiple ways to transform urban public spaces into cultural lounges for people, including domestic and international visitors.

The author is a reporter with the Global Times. life@globaltimes.com.cn