Illustration: Liu Rui/GT

Recent reports and articles from US' and Europe's think tanks and scholars have mentioned that the influence of "third parties" outside the two major powers - China and the US - is on the rise in Southeast Asia. For example, such countries including Japan, Australia and the UK have a relatively positive image among the regional public. Some analysts suggest that these "third-party" countries could use this influence to persuade Southeast Asian nations to embrace US' "Indo-Pacific Strategy" and even support the process of NATO's expansion to the region. Clearly, these views are based on a misunderstanding of Southeast Asia's "preference for a third party." If these "third-party" nations were to act on such assumptions, they would only find themselves falling into a greater strategic misstep.

In fact, Southeast Asia's "preference for a third party" is neither a new discovery nor a novel phenomenon. As early as the Cold War period, countries such as Japan and Australia focused on improving relations with Southeast Asian nations.

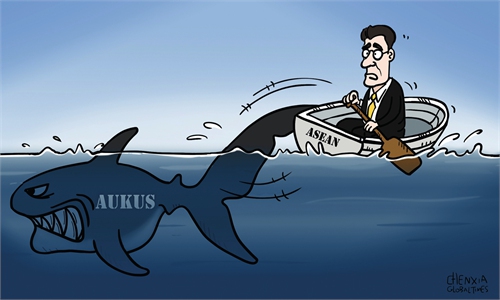

Nowadays, the rising influence of "third parties" in Southeast Asia is essentially due to the increasing strategic resilience of regional countries. Southeast Asian nations are becoming more confident and gradually overcoming concerns about being drawn into great power rivalry fueled by the US government. At the 44th and 45th ASEAN Summits, the US-Philippine push on the South China Sea issue and Japanese Prime Minister Shigeru Ishiba's attempt to promote an "Asian version of NATO" were largely ignored. Other key participants did not get sidetracked but focused on development issues set by Laos, which assumed the ASEAN Chairmanship and took concrete actions to uphold open regionalism and inclusive growth.

In this process, Southeast Asian countries are continuously expanding their cooperation pathways and scope, striving to maintain good relations with more countries and international organizations. The range of "third parties" that Southeast Asian nations prefer has become more diverse and enriched. For example, ASEAN has been deepening its cooperation with the Gulf Cooperation Council, maintaining contacts with organizations such as the Shanghai Cooperation Organisation and the Visegrad Group, and actively increasing its influence in more "Global South" countries. In short, the rising influence of "third parties" in Southeast Asia is a comprehensive and global phenomenon. It is part of ASEAN's strategic autonomy rather than a reflection of the increasing pull of Western countries on the region.

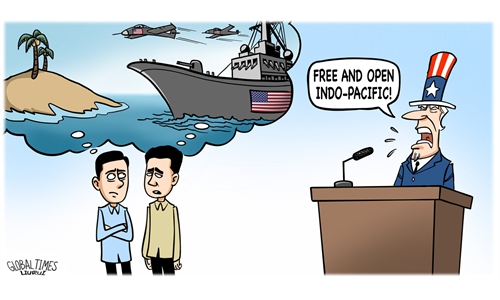

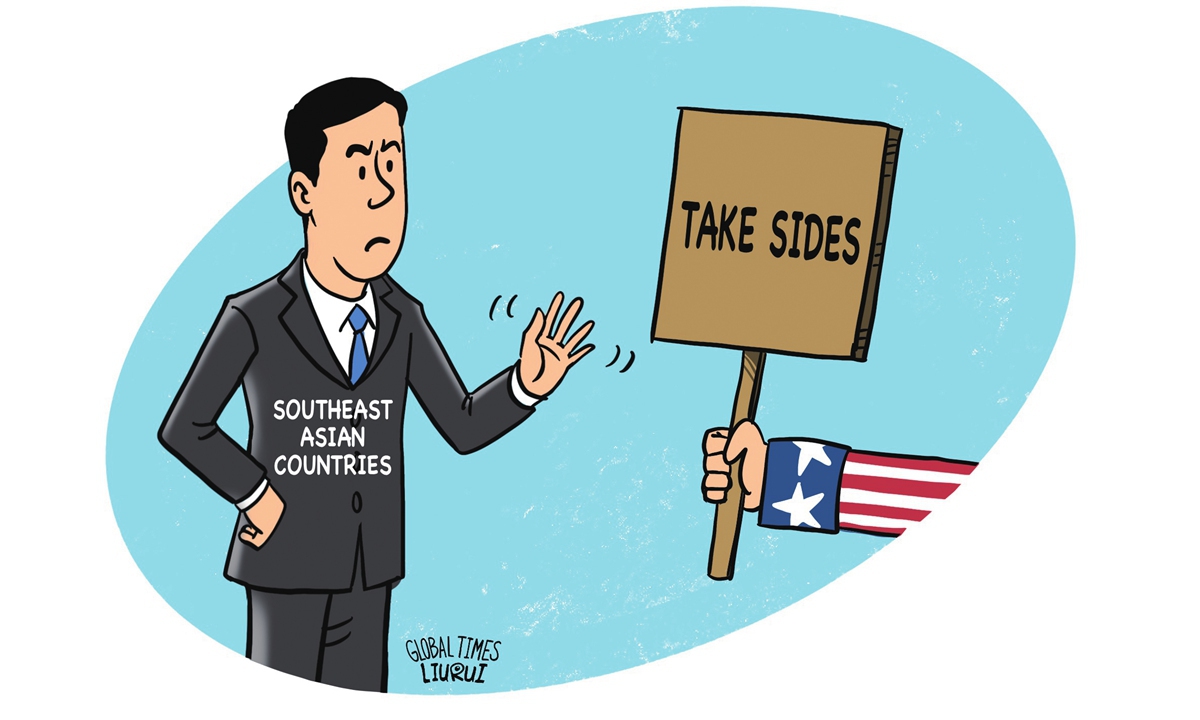

The increased "third-party preference" in Southeast Asia reflects the problems in US policy. In recent years, the US has made various empty promises to Southeast Asian countries. However, it's hard to change Southeast Asian countries' stance to maintain a balance between China and the US and refuse to take sides. The undisguised contempt and negligence of the US have also caused widespread dissatisfaction among Southeast Asian countries. The American magazine Foreign Affairs published an article in September titled "America is losing Southeast Asia," revealing that Southeast Asian countries are gradually deepening their disappointment in the US.

Against this backdrop, the "third-party" countries should not embark on the path of a new cold war incited by some Western voices, but seek to enhance cooperation with Southeast Asian countries. The increased two-way interaction between Southeast Asian countries and relevant "third-party" countries has not only been led by historical factors, but also by realistic strategic considerations.

However, it is worth noting that some "third parties" countries cannot restrain their exclusive mentality and attempt to follow Washington's pace and impose pressure on China while keeping cooperation with Southeast Asian countries. This has aroused the aversion of the vast majority of Southeast Asian countries.

Ultimately, the "third party" countries should have a clear understanding of the current situation, avoid standing opposite to the long-term accumulated order and consensus in Southeast Asia, and not expect Southeast Asian countries to cater to their geopolitical attempts.

The author is an assistant research fellow at the Department of American Studies, China Institute of International Studies. opinion@globaltimes.com.cn