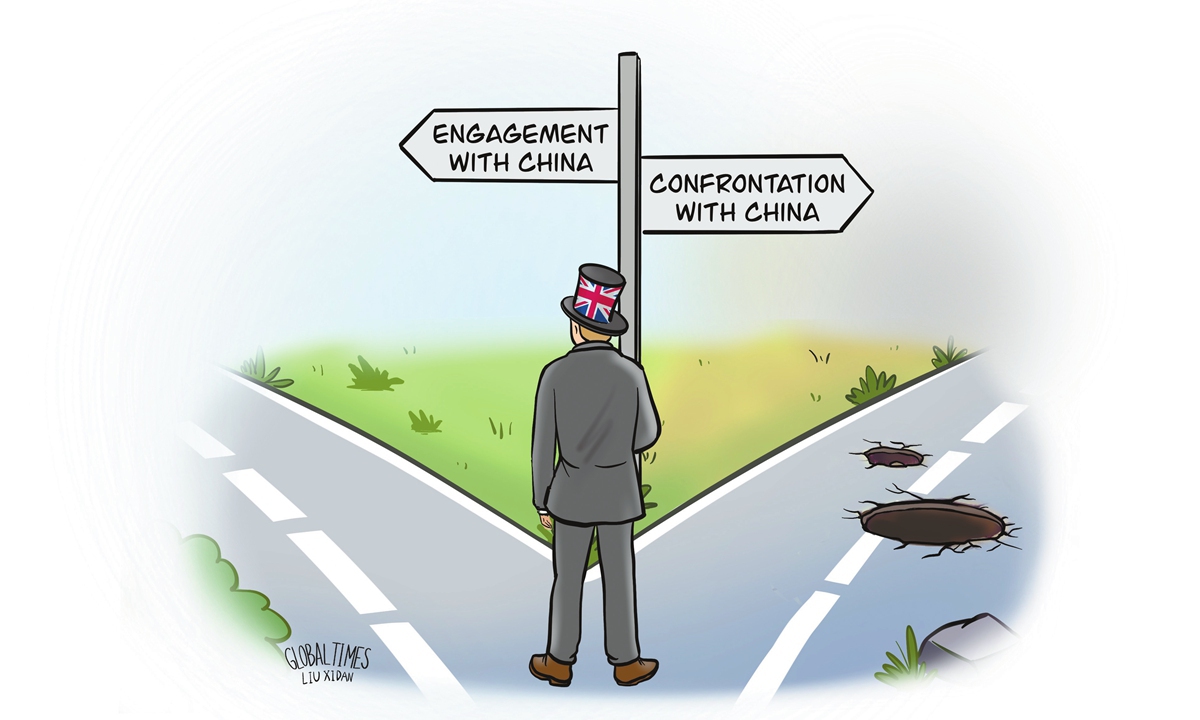

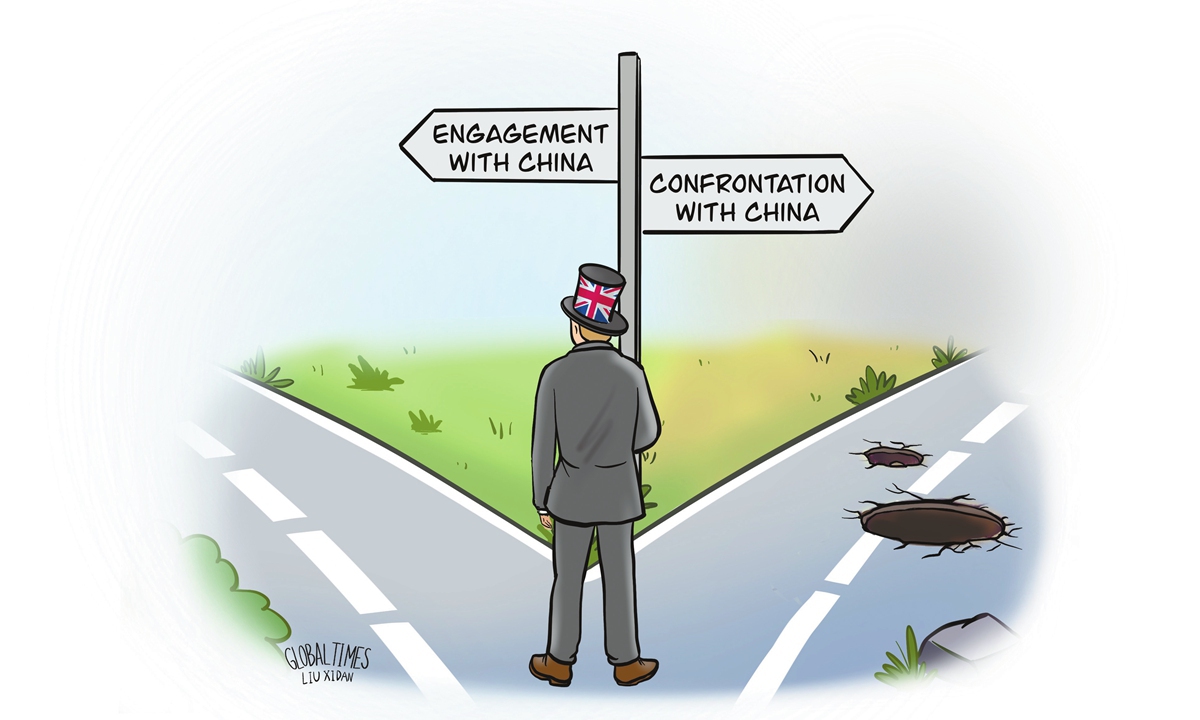

Illustration: Liu Xidan/GT

When Chinese President Xi Jinping met with British Prime Minister Keir Starmer on the sidelines of the G20 summit in Rio de Janeiro on Monday, they spoke through interpreters, but were their words tentatively speaking the language of rapprochement? Less than a year ago, it would have been inconceivable for the UK's prime minister to engage positively with China. But it is remarkable how quickly Downing Street's once icy disparagement of almost anything to do with China seems to be showing early signs of a thaw. There may be clues to this in the language used in Britain's official announcements.

Last month, British Foreign Secretary David Lammy's office used the word "pragmatic" repeatedly to refer to his visit to Beijing and his meetings with Chinese Vice Premier Ding Xuexiang and Foreign Minister Wang Yi.

Then, both in the run up to yesterday's meeting between Xi and Starmer, and in the brief official UK readout afterwards, the prime minister's office used the word "pragmatic" multiple times.

"Pragmatic" seems to be a keyword, though there are others in government statements hinting at a positive change, something that has been missing from diplomatic disclosures for some time.

A close examination of some of the words used by Britain suggests a move toward improving its relationship with China.

One of Starmer's statements referred to areas of mutual interest as "shared goals." The statements also talked about "partnership" and "serious, stable and pragmatic engagement" with China. They mentioned "mutual cooperation" and a "shared responsibility to work together." And the UK pledged to be "a predictable and pragmatic partner" of China. These remarks are all overtly positive in character.

Could it be that Britain is cautiously exploring realistic and sensible ways which will enable it to work with China on solutions to problems, rather than creating them with rhetorical bluster? It would augur well for the UK and China to resume business as usual - literally in some respects - after years of Beijing being cold shouldered by British governments.

The UK might like to think that its message clearly conveys that Britain has turned the page on its recent past in which China was described as "the greatest state-based threat to our economic security." Ministers in the UK routinely accused China of human rights abuses, spying, cybercrime and other offences. Until Monday there had been no meeting between the leaders of China and the UK for six years, yet after his brief session with Xi, Starmer said he hoped the pair would have a "full bilateral" in either Beijing or London.

Yet there is still a long way to go. If there can be clarity on some issues there should be clarity on all. There are some issues on which Beijing and London will not see eye to eye. Starmer himself acknowledged this, saying it was because "our values differ" and "we have different perspectives."

However, if he and his ministers think that tensions caused by Britain's interference in China's internal matters such as Hong Kong or sending Royal Navy warships to conduct provocative patrols in the South China Sea are caused simply by a difference in perspective they may need their eyes tested.

Only last week, Lammy spoke out about the case of infamous anti-China disruptor Jimmy Lai, even though the trial had not yet finished at that time. While British ministers talk of respecting the countries' differences, they seem not to respect the rule of law.

Since coming to power in the summer, Starmer has talked of a consistent, pragmatic partnership with China. But where is the consistency in declaring an intention to reset economic cooperation and then announcing a financial policy whose precise function is to target China's critical mineral sector?

If the British really wish to repair the damaged China-UK relationship, a good place to start would be to put right what has been most wrong with it for years - Britain's confrontational attitude. Warm words and positive messaging mean nothing if they are not followed by concrete action.

Though the apparent change in direction is to be welcomed, Britain should be mindful that good intentions alone are not always enough.

The author is a journalist and lecturer in Britain. opinion@globaltimes.com.cn