Next-phase 'climate debt' of developed countries can no longer be postponed: Global Times editorial

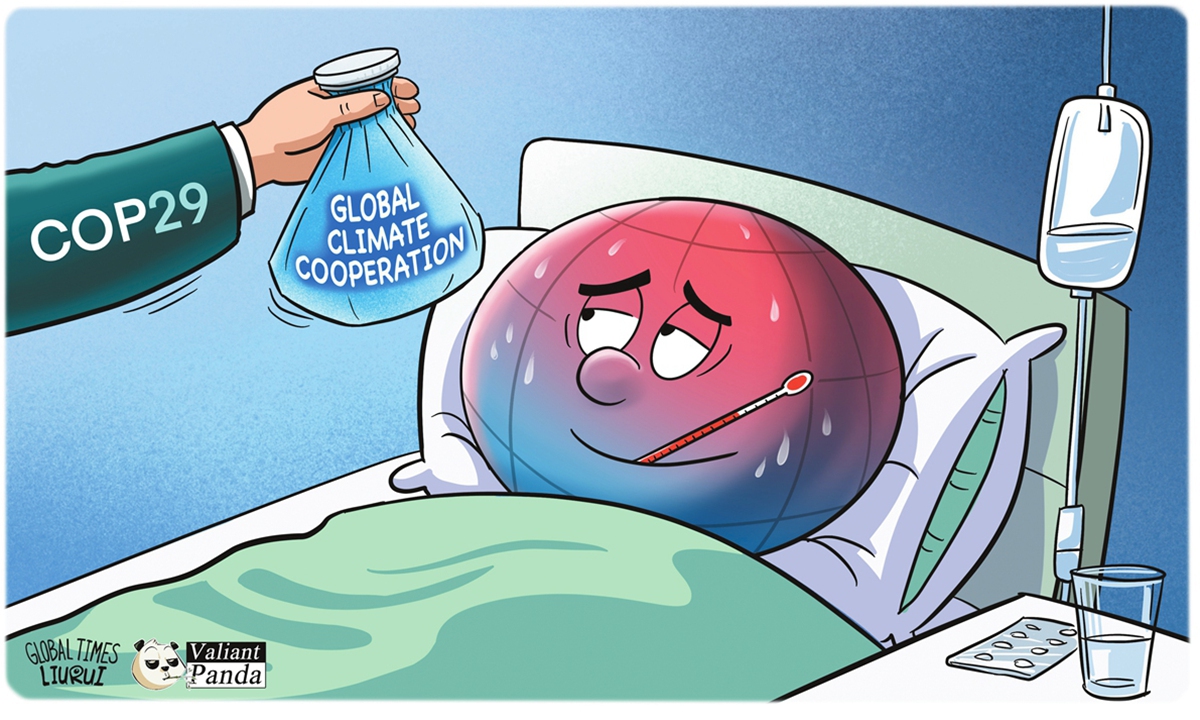

Illustration: Liu Rui/GT

After two weeks of arduous negotiations, the 29th session of the Conference of the Parties (COP29) to the UN Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) finally reached a balanced outcome called the "Baku Climate Solidarity Pact" in the early hours on Sunday local time, after a delay of about 35 hours. Developed countries have committed to leading the way in providing and mobilizing at least $300 billion annually by 2035 to support climate action in developing countries. The conference also called for the mobilization of at least $1.3 trillion annually from various sources for developing countries by 2035.

Public attention has been drawn to the difficult negotiation process at COP29, with significant differences between developed and developing countries, particularly on the crucial issue of climate finance. The $100 billion funding target initially proposed by developed countries was collectively rejected by developing countries.

Under the 2015 Paris Agreement, parties agreed to set new financing goals before 2025, making the core issue and point of contention at COP29 who would contribute, how much they would contribute, and how the funds would be used. Given the frequent occurrence of climate disasters and the climate finance gap, many developing countries had high expectations for the conference, hoping that developed nations would take on their fair share of responsibility.

The achievement of the collective climate finance target marks the adherence and implementation of the consensus that developed countries must provide funding to developing nations under the principle of "common but differentiated responsibilities." While some developed countries attempted to shift the responsibility during negotiations and deviated from the provisions of the Paris Agreement, the strong demands of developing countries led to a final commitment from developed nations to increase their funding from the initial $100 billion to at least $300 billion annually, reaching a package, representing some progress.

Overall, after tireless efforts by all parties, COP29 has offered an imperfect but meaningful pact. As UN Secretary-General António Guterres stated, this agreement provides a base on which to build.

Moreover, in the current complex and challenging international environment, the fact that about 200 contracting parties reached a consensus is remarkable, and ensuring that actions do not regress based on the Paris Agreement is crucial for preserving multilateral processes. China has also consistently made significant contributions to the success of the conference and offered constructive proposals on key negotiation issues.

The international community lacks confidence in whether major developed countries genuinely support global emission reduction plans and can maintain policy continuity and stability. Over the past decade or more, the annual commitment of $100 billion in climate funding from developed countries to developing countries has not been well fulfilled. How much of the newly set $300 billion target will actually be implemented? The intense debates at the climate conference are, to some extent, a reflection of this lack of confidence. As Simon Stiell, executive secretary of the UNFCCC stated, "Like any insurance policy - it only works - if premiums are paid in full, and on time."

It is important to recognize that although the international community shares a common goal in addressing climate change, different countries vary in their stages of development, international influence, and perspectives on the issue. As a result, attitudes toward climate action differ. Therefore, for both developed and developing countries, creating genuine conditions to advance the new energy industries, which is crucial to coping climate change, is likely even more critical.

For instance, China has set a strong example in fulfilling emission reduction commitments, but it has also contributed significantly to green global public goods through the development of its own new energy industries, supporting the energy transitions of many developing countries. Some countries, driven by self-interest, have attempted to label China as having "overcapacity," and have run against global efforts to reduce emissions.

From another perspective, the difficult conclusion of COP29, with a final agreement reached, also highlights that every international consensus reached in addressing climate change, no matter how small, is precious and requires countries to take it seriously and protect it. Funding from developed countries is a means of addressing historical responsibilities, not an act of "charity" toward developing countries - this must not be misunderstood.

In this sense, the international community should exert strong public pressure regarding the next-phase goal of $300 billion set at COP29, and create strong public pressure to ensure that developed countries fulfill their commitments on time and take real responsibility for this "climate debt." This time, they shouldn't default again.