The Underwater Museum of Baiheliang Photo: Courtesy of the museum

Prior to China's Baiheliang inscriptions gaining widespread attention in recent years due to its joint World Heritage application with Egypt's Rawda Island Nilometer, this hydrological heritage that submerges 40 meters beneath the Yangtze River in Fuling district, Chongqing, had already begun to reveal its mysteries since 2009.

In 2009, a design called the "pressure-free cabin" started operating at the Underwater Museum of Baiheliang. This cabin, resembling an immovable submarine, was remarkably ahead of its time and was innovated by China. It epitomizes the country's scientific ingenuity and its tradition of safeguarding cultural heritage.

Immovable submarine "Baiheliang," literally meaning the "white crane ridge," was originally a natural stone ridge that has a history of 1,200 years. It measures 1,600 meters long and is located in the middle of the Yangtze River.

The ridge was engraved with more than 160 inscriptions, which showcase ancient hydrological data, particularly the Yangtze River's low water levels for continuous 72 years starting from the Tang Dynasty (618-907).

"Baiheliang is unique because the ridge's hydrological data is complete and uninterrupted over time. Such a reference has inspired modern projects like the Gezhouba Hydropower Station," Jiang Rui, the museum's director, told the Global Times.

Aiming at preserving the Baiheliang records beneath the river, a total of seven conservation plans have been offered by Chinese scientific teams in early 2000s.

Some of these proposals recommend pulling out the stone ridge from water to land, others too costly, but the "pressure-free cabin" that was proposed by rock mechanics expert Ge Xiurun stood out as the most suitable and pioneering.

"Pressure-free cabin" involves constructing a protective cabin covering the original Baiheliang ridge. It equips with water-cleaning and pressure-evening systems to filter and channel Yangtze River water in and out, maintaining balanced pressure inside and outside of the cabin.

The Underwater Museum of Baiheliang Photo: Courtesy of the museum

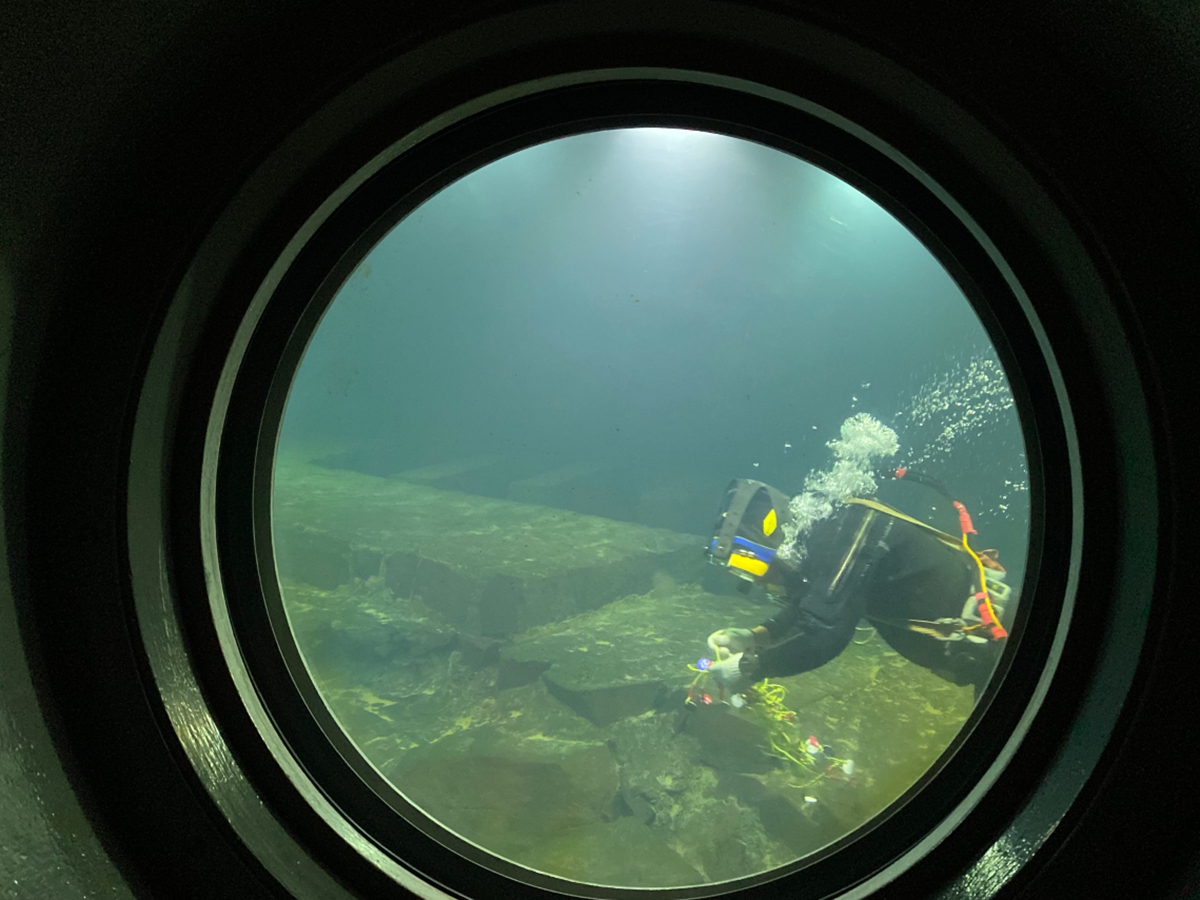

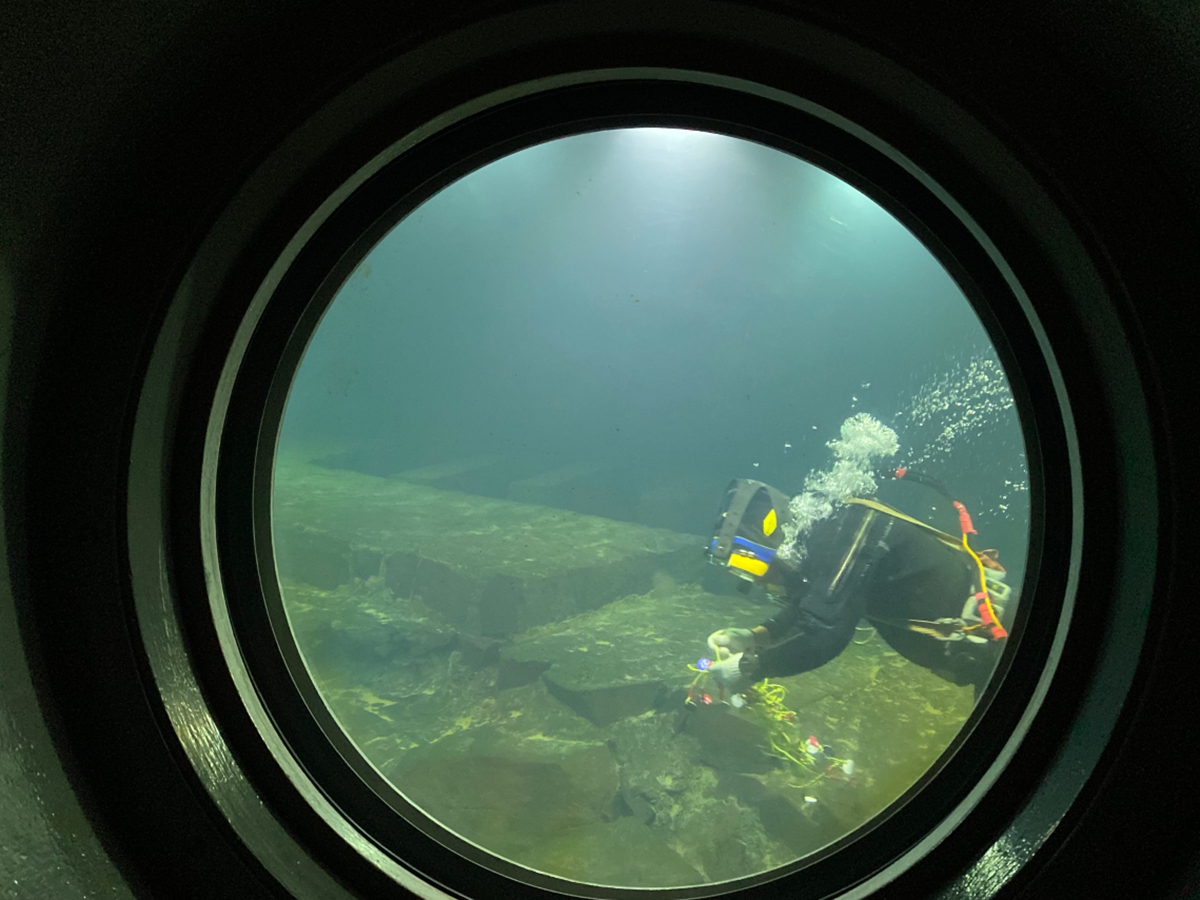

The whole cabin connects two 90-meter-long elevators that can send visitors down into the water. It looks like a futuristic submarine with a silver corridor. Ancient inscriptions are only few meters away when one looks out from circular windows on the wall.

The implementation of the "pressure-free cabin" plan has made the Baiheliang site the only underwater heritage museum in the world accessible without diving.

"The underwater scenes are beyond imaginable. The inscriptions are still so clear and they made me appreciate the richness of ancient Chinese culture," Grace, a visitor from Kenya, told the Global Times.

Noting the device operates like a "never-stopping machine," Liu Bin, head of the museum's equipment division, said that inside the cabin, there are more intricate systems designed for lighting, gas supply and relics cleaning. Although the "submarine" can no longer undergo major rebuilt, its facilities have been improved over the years to offer better experiences to visitors.

Taking the circular window as an example, the current window glass has been updated to the same kind of material used on the J-20 stealth fighter. To reduce the growth of underwater organisms on the ridge, the lighting system has been updated. Jiang, the director, said that the team is now incubating a latest lighting plan, to make the ridge "become a stage-like and major inscriptions will be highlighted."

"It is because of such scientific preservation measures, the humanistic value of Baiheliang inscriptions can be recognized by the world," Jiang emphasized.

A visitor observes stone fish inscriptions at the Underwater Museum of Baiheliang. Photo: IC

'Romantic spirit' Although Baiheliang inscriptions were used documenting water data, many legacies on the ridge actually hold artistic details; revealing how ancient Chinese people expressed their sentiments through connecting with nature.

On one of the stone steles, Northern Song Dynasty (960-1127) intellectual and calligrapher Huang Tingjian inscribed on the ridge to express his reluctance to leaving Fuling.

On another stele, Huang Shou, the ancient governor of Fuling district during the Ming Dynasty (1368-1644), engraved a poem on Baiheliang. Huang Shou used the classic stone fish pattern on the ridge as a symbolic representation to express his will of being an honest governor.

Not far from Huang Shou's underwater poetry is the museum's pearl, the stone fish inscriptions. This group of stone fish inscriptions were created in two different dynasties of the Tang and Qing. By observing the position of those fishes' eyes and fins, the ancient people were able to accurately track the river's low-water data.

A staff member of the Underwater Museum of Baiheliang works underwater. Photo: Courtesy of the museum

Compared to many hydrological heritage sites such as the Rawda Island Nilometer that is focused on pragmatism, the Baiheliang's poetry and calligraphic legacies have made it a good representation of "ancient China's unique romantic spirit," Jiang said.

"When I walked underwater and saw these inscriptions, I felt the unique ways how ancient Chinese people expressed themselves. China is an ancient civilization, so it possesses many cultural heritage sites. These treasures belong to China, but they offer inspiration to people around the world," Nicolas Deschamps, a French documentary director at the museum, told the Global Times.

In 2023, China and Egypt reached an official agreement to launch a joint World Heritage application featuring the Baiheliang inscriptions and the Nilometer at the Rawda Island.

This application is now at a stage of discussing core issues such as "their similarities" as well as conducting an "comparative analysis" between the two sites. Jiang revealed to the Global Times that by the end of 2024, China and Egypt will sign a Memorandum of Understanding to facilitate more details.

"Our collaboration with Egypt enhances the developing countries' discourse power in interpreting their importance in protecting cultural heritages worldwide," Jiang emphasized.