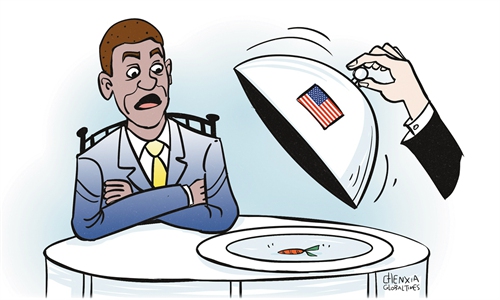

Can US’ strategy to sideline China in Africa succeed?

Illustration: Chen Xia/Global Times

My trip to Africa this past August gave me a deeper understanding of the continent.

Behind every rickety minibus speeding through muddy roads, every flickering light bulb, and every village surrounded by dusty dirt roads lies a story of resilience and strength that is nothing short of awe-inspiring.

At the same time, every African nation, especially those rich in resources yet trapped in poverty, seems to silently convey a stark truth to the outside world: the lack of infrastructure is choking the future of Africa's development.

The Americans arrived just as I reflected on the glaring infrastructure gaps across the continent.

They came with the Lobito Corridor railway project, a shiny package wrapped in 5G, artificial intelligence and the Internet of Things. They also brought a savior-like attitude, as if they were here to deliver Africa from the quagmire of transportation paralysis and economic stagnation. Such a high-level modern engineering project does not even exist in the US.

Washington has hyped this railway, connecting Angola, the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC) and Zambia, as something that could even "reshape the economic landscape" of the region. It certainly sounds like an ambitious and grand narrative.

But when I examined the railway's plans more closely and listened to the perspectives of a few African friends, I realized that this is far from a straightforward American success story. There are layers of complexity and ulterior motives beneath the surface.

The Lobito Corridor is touted as a flagship railway project incorporating cutting-edge technologies like 5G, cloud computing and IoT. Its purpose is to link the DRC's mineral-rich regions to Angola's Lobito Port for export. One of its stated goals is to reduce Africa's dependence on foreign-dominated supply chains, while also claiming to help African nations process their own resources.

This railway has been packaged as the future of African industrialization. But if you underline the words "mineral resources," you'll uncover the story's real focus: who gets to control Africa's minerals.

These minerals, whether cobalt or copper, are essential for the green energy revolution. From this perspective, the Lobito Corridor could indeed be described as a "golden corridor." But the Americans have carefully hidden another side to this story. This railway is designed to make Africa's mineral resources flow faster, cheaper and reliably to Western countries.

The US didn't just secure cooperation among three African nations for the Lobito Corridor. It also played a geopolitical game. The Americans have openly intended to push China out of Africa's supply chains. For the US, this project is nothing more than a geopolitical pawn. It's part of a broader strategy to "reassert its influence" in Africa and "liberate" the continent from China's so-called control.

In contrast, China's infrastructure projects in Africa - whether roads, railways, or ports - are often designed to connect landlocked nations to coastal regions, fostering industrial growth and market activity.

For example, Kenya's Standard Gauge Railway (SGR) has finally provided modern rail transport services for local industries. Many of China's projects focus on connectivity and even help African nations move up the value chain by encouraging local resource processing.

By comparison, the Lobito Corridor feels much more limited in scope. It carries a strong whiff of colonialism, reminiscent of the old playbook where railways were built to extract resources and funnel them to ports for export to Western countries, the old colonists. The only difference is that the colonialists have been replaced by AI, IoT and 5G.

It is not about creating a cooperative platform but building a supply chain aimed at competing with China. For years, China has been deeply committed to fostering cooperation with Africa and has established strong connections within Africa's development framework. If Washington's strategy is to sideline China in Africa through strategic pressure, can such a project truly succeed?

African nations need railways, roads, electricity and communication networks. However, this infrastructure must serve Africa's development, not just as a lifeline for international capital or a battleground for global power struggles that force African nations to pick sides.

Africa truly needs partners who can help it build a future on its own terms - not "saviors" in new clothes who see Africa as their strategic resource to control the world.

The author is a senior editor with the People's Daily, and currently a senior fellow with the Chongyang Institute for Financial Studies at the Renmin University of China. dinggang@globaltimes.com.cn. Follow him on X @dinggangchina