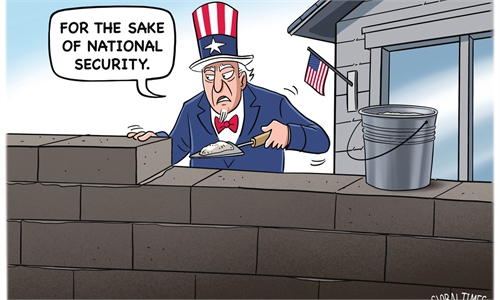

Illustration: Liu Rui/ GT

The US government's recent scrutiny of Chinese-made routers is another chapter in Washington's never-ending "China paranoia." This time, TP-Link, a Chinese technology company that dominates more than 60 percent of America's home router market, is under investigation.

According to CNN, US officials are investigating potential national security risks tied to the Chinese company whose internet routers are used by millions.

For Washington, if a final decision is made to ban the sale of Chinese-made routers, it may satisfy a political imperative to "do something" about Chinese technology. However, the reality is far more sobering: Banning Chinese routers is an uphill battle the US can neither sustain domestically nor enforce globally.

Let's start with the immediate domestic challenge. Millions of American households depend on Chinese-manufactured routers, such as TP-Link, for affordable and reliable internet connectivity. For these families, switching to alternatives would mean paying hefty premiums for routers made by domestic or allied manufacturers, which cannot match the scale or efficiency of Chinese production. This cost would primarily be shouldered by lower- and middle-income households, further exacerbating existing economic pressures.

Additionally, the US lacks a clear roadmap for replacing Chinese-manufactured routers, both in terms of availability and affordability. Global supply chains for network technology are deeply intertwined, and Chinese manufacturers have become integral to everything from the smallest components to the final assembly line. Cutting off Chinese routers would cause significant disruption, delay new rollouts, and ultimately undermine core American industries and small businesses that rely on competitively priced network technology to survive.

But even if the US were willing to stomach the economic fallout at home, its influence ends at its borders. Globally, Chinese brands dominate the networking equipment markets of many emerging economies, providing affordable solutions where Western companies can't compete.

Countries in Africa, Southeast Asia, and Latin America won't stop buying Chinese routers just because Washington says so. An American ban won't rewrite the rules of global trade. Chinese-made routers, even under the weight of geopolitical scrutiny, will continue to thrive internationally as key players in developing markets that the US does not - and often cannot - serve.

Faced with these obstacles, why does Washington persist? The answer lies less in hard evidence and more in political theater.

For US policymakers, any Chinese-made networking equipment is assumptively guilty of jeopardizing national security, even if no concrete evidence supports such a claim.

"Made in China" has become shorthand for "potential threat" in Washington's vocabulary. This conditioned response offers immediate political benefits - appearing vigilant and tough on China - but does little to address widespread systemic vulnerabilities across all networking devices, regardless of origin.

What Washington fears most is not necessarily evidence-based; the idea of not acting against China has become politically untenable. It seems that the entire daily job of some officials in Washington is to search for traces of security or human rights issues in products made in China. However, this paranoia comes at a steep cost. By targeting China with blanket bans, the US inadvertently accelerates China's push toward self-reliance, particularly in tech sectors like semiconductors and networking.

At home, this "China paranoia" harms ordinary Americans, too. Forcing consumers to spend significantly more on domestically produced alternatives while the global supply chain struggles to adjust represents a lose-lose scenario. More expensive routers lead to higher costs for small businesses, educational institutions rolling out internet infrastructure, and rural communities trying to modernize.

At its heart, this policy reflects a psychological obsession rather than a rational strategy. It's easier to ban a product than to undertake the painstaking work of securing networks and educating users. It's easier to blame China for perceived vulnerabilities than to address weaknesses in American innovation or global collaboration.

In the end, the US might successfully ban Chinese routers from its domestic market. However, it won't be able to eliminate Chinese manufacturers' global dominance or replace their role in the supply chain overnight. What Washington risks achieving instead is a situation where it pays the price for paranoia with diminished competitiveness, rising costs, and an increasingly isolated position in a globalized world.