Illustration: Xia Qing/GT

The incoming Donald Trump administration will not be a rerun of his first presidency. The incoming administration in the US will possibly mean: the end of post-1945 American multilateralism; a growing gulf between Europe and the US; the end of the Ukraine war; a trade war with China (but not a hot one) which will fail in its objectives; and major pressure on all US allies (European and East Asian) to pay for part of their defense. It will mark a paradigm shift on a far bigger scale and of far greater consequence than previous such shifts like the Thatcher neo-liberal revolution in the 1980s. It will mark a major shift to the right in US politics, a large-scale retreat from America's global role, and a return to America as the overwhelming priority.

The incoming Trump administration poses a profound crisis for Europe. Europe has invested huge economic, political and military capital in the Ukraine war, which the US president-elect is committed to ending on terms that will represent an embarrassing defeat for Europe. His insistence that America's allies should shoulder a much larger share of their defense, and America much less, is deeply problematic for the relatively weak European economies and, more importantly, an existential threat to the transatlantic alliance system based on NATO.

The incoming US administration's challenge is as much economic as security. It is threatening to impose more duties on European imports. The picture is even more bleak when viewed in a longer-term context. Since 2009, US GDP per capita has almost doubled while that of the eurozone has grown by less than 20 percent. Europe has singularly failed to develop its own tech giants. Politically, the EU lacks strong France-Germany leadership and finds itself increasingly divided. Meanwhile, the far right is on the rise in most countries. It is difficult to be optimistic about Europe's future. There are only two major powers, China and the US.

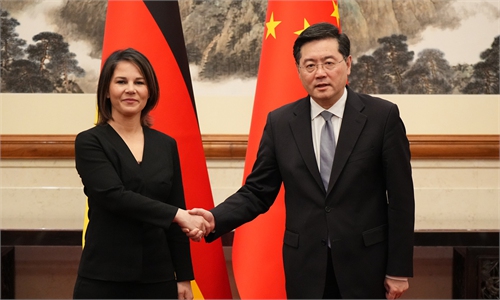

In view of the incoming US administration, Europe will need China much more. It can no longer afford to be on bad or even indifferent terms with China, as it has been. But that will only be possible if Europe distances itself from US attempts to isolate China. A classic example was the way many European governments bowed to US pressure on 5G. In this context, Europe must learn to respect Chinese policies on Hong Kong and Xinjiang affairs, for example, even when they disagree with them. The shift in tone and approach by the new UK Prime Minister Keir Starmer may be instructive in this context. He is refusing to grandstand against China on these kinds of issues, insisting that economic and environmental cooperation must take priority. This approach could be regarded as an implicit acknowledgement that the Chinese are deeply offended by what they see as the exercise of moral superiority by Europe toward China born of habit and history. If Europe wants to upscale economic and environmental cooperation with China, it must stop treating China like a disobedient child. European civilization must recognize and respect Chinese civilization as its equal.

This should be seen in a broader context. Europe has long regarded China as its economic inferior. This mentality is an anachronism. Europe's electric vehicle (EV) crisis is living proof.

China has shown itself to be Europe's superior in many different respects: long-term thinking, superior mode of production, comprehensive supply chains, battery innovation and production, much cheaper products, and a recognition that EVs are part of the tech rather than the automobile industry. Raising tariffs on Chinese EVs is patently not the answer to the crisis of the European car industry. It must be recognized that any solution for the European car industry is dependent on a new form of cooperation with China's EV and battery industries. Chinese capital and know-how are indispensable for the future of the European car industry.

Europe needs to learn from China. Not just in EVs but also in other areas, green technology being an obvious area. Europe once thought of itself as a leader in this field, but alas no longer. China has assumed this position. More generally, Europe, as in EVs, is increasingly going to need Chinese investment and technology.

Its firms should seek to form partnerships with Chinese companies and should welcome Chinese investment in Europe as a way of learning and catching up. If technology transfer was once crucial to China's efforts to modernize, now Europe must do the same if it is to compete in the growing number of areas in which it finds its technologically behind.

Can European attitudes engage in such a paradigm shift? Time will tell. A lot of old prejudices will need to be abandoned in the process.

The author is a visiting professor at the Institute of Modern International Relations at Tsinghua University and a senior fellow at the China Institute, Fudan University. Follow him on X @martjacques. opinion@globaltimes.com.cn