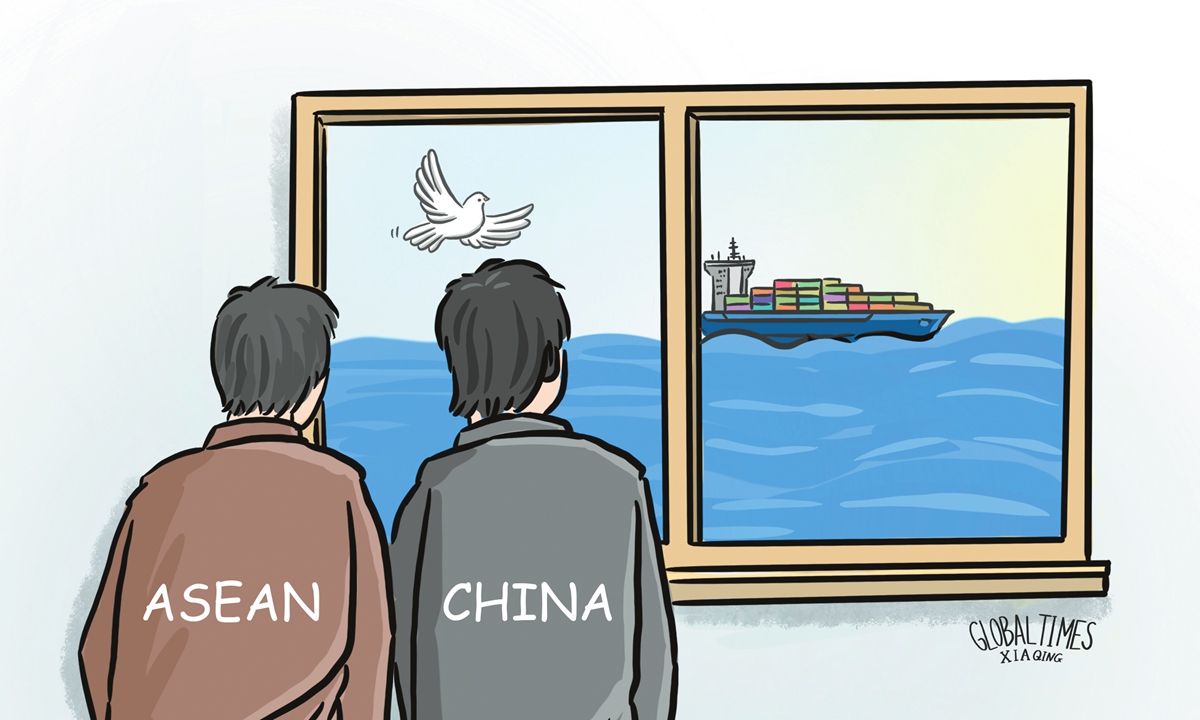

Illustration: Xia Qing/GT

Recently, senior officials from the Philippine defense department and navy have repeatedly denigrated China's South China Sea dotted line as "lies" and a "joke." They have sought to recast the territorial and maritime disputes between the two countries in the South China Sea as a broader issue involving China and ASEAN, disregarding historical and legal foundations and revealing malicious intentions.The dotted line in the South China Sea serves as a vehicle for expressing China's rights and claims in the region. In response to the illegitimate ruling of the South China Sea arbitration case, the Chinese government issued a statement on China's territorial sovereignty and maritime rights and interests in the South China Sea in July 2016, reaffirming China's territorial sovereignty and maritime rights. It clearly states that China has territorial sovereignty and maritime rights and interests in the South China Sea, including, inter alia: China has sovereignty over Nanhai Zhudao, consisting of Dongsha Qundao, Xisha Qundao, Zhongsha Qundao and Nansha Qundao; China has internal waters, territorial sea and contiguous zone, based on Nanhai Zhudao; China has exclusive economic zone and continental shelf, based on Nanhai Zhudao; China has historic rights in the South China Sea.

First, China has claimed and enjoyed maritime rights in the region under international law, including the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea, and has never relinquished any of its established historic rights, which may be of a sovereignty or a non-sovereignty nature. In its Law on the Exclusive Economic Zone and the Continental Shelf (1998), China affirmed its rights to the exclusive economic zone and continental shelf, stating that no provisions of this law can prejudice the historic rights of China. Accordingly, China's historic rights and its rights to the exclusive economic zone and continental shelf can coexist; they are cumulative when they overlap.

Second, China's sovereignty over Nanhai Zhudao and its historic rights in the South China Sea have been long established. Since long ago, China has exercised jurisdiction over Nanhai Zhudao and relevant waters, encompassing its archipelagos and relevant maritime areas, without distinguishing between land and water.

Third, in the process of the long-term development of the South China Sea, the Chinese people have formed a deep understanding of its natural geography, and have made the South China Sea their home. No later than in the early Ming Dynasty, fishermen from Fujian, Guangdong, Hainan and Guangxi on China's southeast coast, sailed on the north-easterly monsoon in winter southward to Xisha Qundao, Zhongsha Qundao and Nansha Qundao for fishing activities. During this process, some fishermen went to Southeast Asia to trade in aquatic products. Chinese fishermen recorded their experiences and navigational routes in concise entries within handwritten booklets, which not only documented geographical names and sailing routes in the South China Sea but also contained a large amount of important nautical information.

Fourth, the territorial and maritime delimitation dispute between China and the Philippines in the South China Sea has been in existence for years. The dotted line referred to in the Philippines' submissions was first marked on an official map China published in 1948, and has remained in China's official maps consistently ever since.

In the Fisheries Case, the United Kingdom argued that it was not aware of the Norwegian system of delimitation with respect to straight baselines, asserting that the system therefore lacked the notoriety essential to provide the basis of a historic title enforceable against it. The Court did not accept this argument and observed that, as a coastal state on the North Sea, greatly interested in the fisheries in this area, as a maritime power traditionally concerned with the law of the sea and concerned particularly with defending the freedom of the seas, the United Kingdom could not have been ignorant of the Norwegian practice which had at once provoked a request for explanations by the French government.

Similarly, the Philippines, as a coastal state of the South China Sea, has great interests in the sea areas and has always paid close attention to China's activities at sea. It could not have been ignorant of China's relevant practices. The Philippines, fully aware of the dotted line marked on China's official maps published since 1948 and historic rights referred to in the 1998 law, had never raised any question. Here, an acceptance or acquiescence obviously exists.

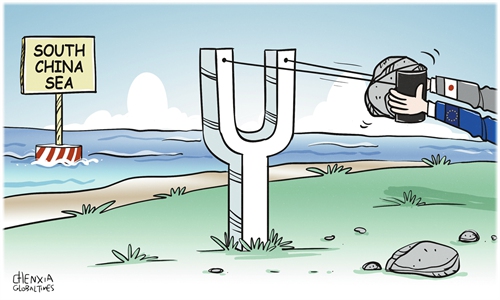

Finally, the "freedom of navigation" issue is a manufactured concern, amplified by external powers to justify military presence and political leverage. The South China Sea is home to a number of important sea lanes, which are among the main navigation routes for China's foreign trade and energy import. Ensuring freedom of navigation, overflight and the safety of sea lanes in the region is crucial for China. Over the years, China has worked with ASEAN member states to ensure unimpeded access to and safety of the sea lanes in the South China Sea and has made an important contribution to this collective endeavor.

The author is the director of the Center for International and Regional Studies, National Institute for South China Sea Studies. opinion@globaltimes.com.cn